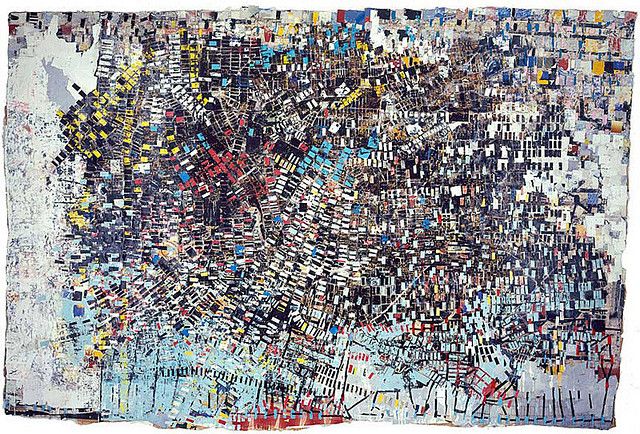

Mark Bradford, Black Venus, 2005. Berezdivin Collection, Photo: Bruce M. White. Courtesy of www.themarkbradfordproject.org.

The Harvard Design School occupies the core of my mental campus map. Inside the efficient Bauhaus structure, I imagine, designers construct precise models for future spaces. They synthesize and restructure theories from around the university, as they fit them into physical frameworks of steel, Plexiglas, and wood. Unlike most Harvardians, these academics make things. They belong to the real, physical world.

At first, the recent exhibit at the Design School seemed to confirm this image. Maps on walls and in display cases rendered spatial indicators—topography or population or climate—in aesthetically pleasing visual codes. Design students’ experiments in cartography shared space with gorgeous, abstract expressionist visions. The exhibition’s title, however, is “Cartographic Grounds: Projecting the Landscape Imaginary”—despite their apparent exactness, the facts and figures portrayed by these maps are fictional.

A course I’m currently taking, “Stranger Than Fiction” with Carrie Lambert-Beatty, examines contemporary art projects that perform fictions as if they were true, everyday events. We have examined a utopian version of The New York Times dated six months in the future; artists who have assumed alternate personas for large portions of their lives; and museums that have staged excavations of their facilities, revealing the buried artworks of invented actors. All of these projects have gained criticality, or the ability to challenge existing philosophies and social structures, through this fictional strategy. After revealing themselves to be fictions—after shaking off their cloaks carefully stitched into the fabric of the everyday—these projects force us to reevaluate conventional structures and to question our usual perceptions.

The maps at Harvard’s Design School are not as critical, or at least not in the overtly political sense. Unlike the critical fictional projects, the initial viewing experience of these maps does not seem less legitimate after the project’s “big reveal”: the maps’ subjective schemes for processing a landscape seem to speak more to our experienced interactions with the world than any factually correct graph of data might. These mappings of associated colors and walk patterns suggest the way in which memories and associations color my own interactions with a space. As I leave the exhibition, I’ll reenter campus, processing Cambridge Street with an additional lens of color, or walk pattern, or topographic layer. They also recall the invented interpretive schemes of digital technology in general: these maps are not fictions but rather technologies that inform our everyday experience. Perhaps “fiction” in contemporary art operates increasingly, then, as a function of our digitally influenced and designed environment—and not exclusively as a theoretically produced, political tool. Carrie Lambert-Beatty’s seminal essay on the strategy, “Make-Believe: Parafiction and Plausibility,” does not explicitly argue that these projects predominantly serve activist purposes. But responding theorists like Jose Falconi have suggested its primary function as a challenge to the status quo.

Artists and architectural designers (however arbitrary a distinction that may be) have increasingly overlapped in method and aim in recent years. Art Forum published a roundtable in last month’s issue that discussed the architectural concerns of much contemporary art. Olafur Eliasson, for instance, has researched principles of light and physics to produce immersive, architectural environments, and Hilary Lloyd has explored the architecture of film installations[1]. Mixed media “painters” Mark Bradford and Julie Mehretu have produced their own visual languages to signify the contemporary landscape. In their vast and textured versions of regional Google Earth images, and in their complex arrangements of minute, geometric shapes, Mehretu and Bradford encode a contemporary landscape that is, paradoxically, local and global; abstract and representational; actual and virtual. Discussions about the architecture of museums also take place within this larger debate about the role of art today.

Digitalization has helped to generate this trend—in many ways it can be interpreted as a resurgence of the early twentieth century’s dominant philosophy on art, which saw architecture as the structuring logic of an ideal model of art production. Digitalization inevitably charges architects with artists’ traditional roles: the virtual projections of landscapes at the Design School seem more apt for building environments than any physical structure would be. To build—to ensure successful reception of their environments despite increased levels of mediation between maker and audience—architects must first produce artistic visual schemes. These maps’ visualizations of a space enhance the cognitive maps we habitually use. Though the ribbons of color and figural themes may not challenge the foundations of aesthetic experience, this is not to say that they or similar artistic-architectural works are not political, nor that they lack the potential to be. After nearly a century of confrontational interventions and abrasive shocks to aesthetic experience, maybe this digital age we live in offers new and more pleasurable possibilities for the fusion of art and life. The challenge for these artist-architects would then be to preserve these aesthetics, as they steer their art back towards the process of democratization. For now, these images steer my mental map: absorbing the topographical strata in purple and yellow hues, organizing the shifting sensations into a pattern of lines and dots.

[1] Demand, Thomas, Hal Foster, Steven Hall, Sylvia Lavin, Hillary Lloyd, Dorit Margreiter, Hans Ulrich Olbrist, and Philippe Rahm. “Trading Spaces: A Roundtable on Art and Architecture.” Interview by Julian Rose. Art Forum, October 2012.