DIAGNOSIS, IN FIVE ACTS

ACT I: DIAGNOSIS AS POLITIC

In March 2025, we emailed Lisa Mendelman, an Associate Professor of English and Digital Humanities at Menlo College, who has worked on the intersection of mental health diagnoses and race, gender, and affect. Her current book project, Pathologies of Character: Race, Gender, and the Medicalization of Mental Health and American Literature, 1890-1955, investigates how race, gender, sexuality, and class have shaped psychiatric diagnoses. We asked her how she was conceptualizing “diagnosis” in the present age. Here’s what she wrote in return:

We’re in a time where the negative consequences of diagnosis seem to be scaling up rapidly. When you tell people you’re writing a book about the history of mental health, people tend to say some version of “how timely!” Yet I don’t think anyone – certainly not me – anticipated how timely it would become after January 20.

In February, I twice rewrote my National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant—first to remove the World Health Organization (WHO) and then to mitigate the DEI language in the title and prefatory documents. I ultimately decided to leave the core of the application untouched, because it was simply too important to me to preserve the project as I imagine it. When I write, I spend an inordinate amount of time considering the precise right word in each instant. Replacing “race, gender, sexuality, and socioeconomic class” with “social categories of identity” feels like stirring up silt in what was clear water. And of course, the murky version also points to something likely to be a target for federal cuts.

I called two months after Mendelman went through this iterative revision process. We spoke over the phone; Mendelmann had a kind voice and hesitated to speak in absolute truths. At the time, it felt like DEI language – rhetoric that invokes the principles of diversity, equity, and inclusion – was a creeping infection. A single poisonous word could contaminate an entire grant.

Yet, for many, the cancer was impossible to locate. By April 2025, $2.3 billion in funds allocated to researchers had been pulled by the NIH. Scientists were told that their grants had been terminated because their studies were “based primarily on artificial and non-scientific categories, including amorphous equity objectives.”

ANNIKA INAMPUDI: Is there a way to talk about diagnosis without DEI language?

LISA MENDELMAN: You can’t. There’s no way to do science without an awareness of who’s in the patient population you’re talking about. I’m terrified of what this moment means for the future of public health.

AI: Do you see a relationship between your work and the present Administration, who is very obsessed with classifying– or even demonizing some forms of classification over others?

LM: Part of what’s going on is the use of artificial intelligence to identify certain language and diagnose it as “problematic.” It’s about diagnosing an ideology as reflecting a narrative of American inferiority, and trying to correct for it by erasing it.

A useful frame for me, as a historian, has been viewing this moment through the lens of a reaction to leftist political correctness. Although, I don’t know. I’m always interested in what the precedent is for what we’re going through. Not that they always make me feel better– but, at least they make me feel less unmoored.

ACT II: DIAGNOSIS AS A VERB

In Mendelman’s work, she often distinguishes two definitions of diagnosis, equally pertinent to one’s conception of the term. At once, diagnosis is a medical tool to discern pathology from wellness, and a much broader process of classification and assessment. Both definitions underlie the same contradiction – they are constraining yet freeing, objective and subjective, individual and social. “Diagnosis aspires to neutrality as a route to authority,” she writes, “which paradoxically shores up its subjective vantage point.”

AI: In your article, “Diagnosing Desire,” you mention deliberately using the term ‘diagnosis’ as a verb. Can you explain what that approach means to you?

LM: I am always acutely aware that my perspective on diagnosis is informed by the fact that I am not a clinician. When one goes to see a physician, a lack of diagnosis generally corresponds to a failed clinical encounter, right? There’s a tremendous amount of pressure and desire on everybody’s part to have an explanation for what’s going on.

That’s very different from when one is a historian – and I mean historian in the context of being someone who also thinks about the present moment – to think about the subjectivity involved in arriving at the label of diagnosis. The whole idea of diagnosis as a verb, diagnosis as a doing, is a luxury. There is a luxury that comes from not needing to think about diagnosis as a noun, because someone’s mortality doesn’t hinge on a diagnosis. To say diagnoses are racist, diagnoses are sexist, diagnoses are classist, etc. is to think of them as a verb, or as a process. I’m not anti-diagnosis, or anti-science, but rather I see myself aligned with the project of science and medicine and diagnosis itself, which is to try to get closer to more and more accurate descriptions of what is going on in the mind and body.

AI: There’s less urgency associated with history, maybe. And so you have the luxury of being able to think about the process.

LM: Yeah, there’s less medical, mortal, necessity.

AI: I’ve been reading Rachel Aviv’s Strangers to Ourselves. In it, she talks about diagnosis as something that’s both constraining and freeing, but it depends on the person you are, or the authority of the clinician, or something else entirely. As Aviv writes: “People can be freed by these stories, but they can also get stuck inside them.” How do you deal with that dichotomy of the term in your work?

LM: We all contain those conflicts. In any given moment and in any given context, diagnosis can range from constraint to freedom. Those feelings can also evolve and shift over time. Diagnoses can provide legitimacy to one’s experience; it can provide a sense of trajectory forward; it can open up treatment options. But all those things have a shadow side as well. There’s potentially a record for an insurance company that wants to deny coverage; or a dire prognosis. A diagnosis is mobile, and labile, and fluctuating.

AI: But it's also a reification, in some ways.

LM: Diagnosis can be multiple things in the same moment. Think about a cancer diagnosis: there’s the relief of having an explanation and the possibility of treatment and there’s a feeling of devastation.

One of the other challenges of diagnosis has to do with the authority of the person rendering the diagnosis. In the age of WebMD and artificial intelligence and self-diagnosis – do you trust the person doing the diagnosis, or the person that you’re doing the diagnosis on, and so forth? There’s a relational quality to it, and a sense of faith in science.

ACT III: DIAGNOSIS AS A CONSTRUCTION OF PERSONHOOD

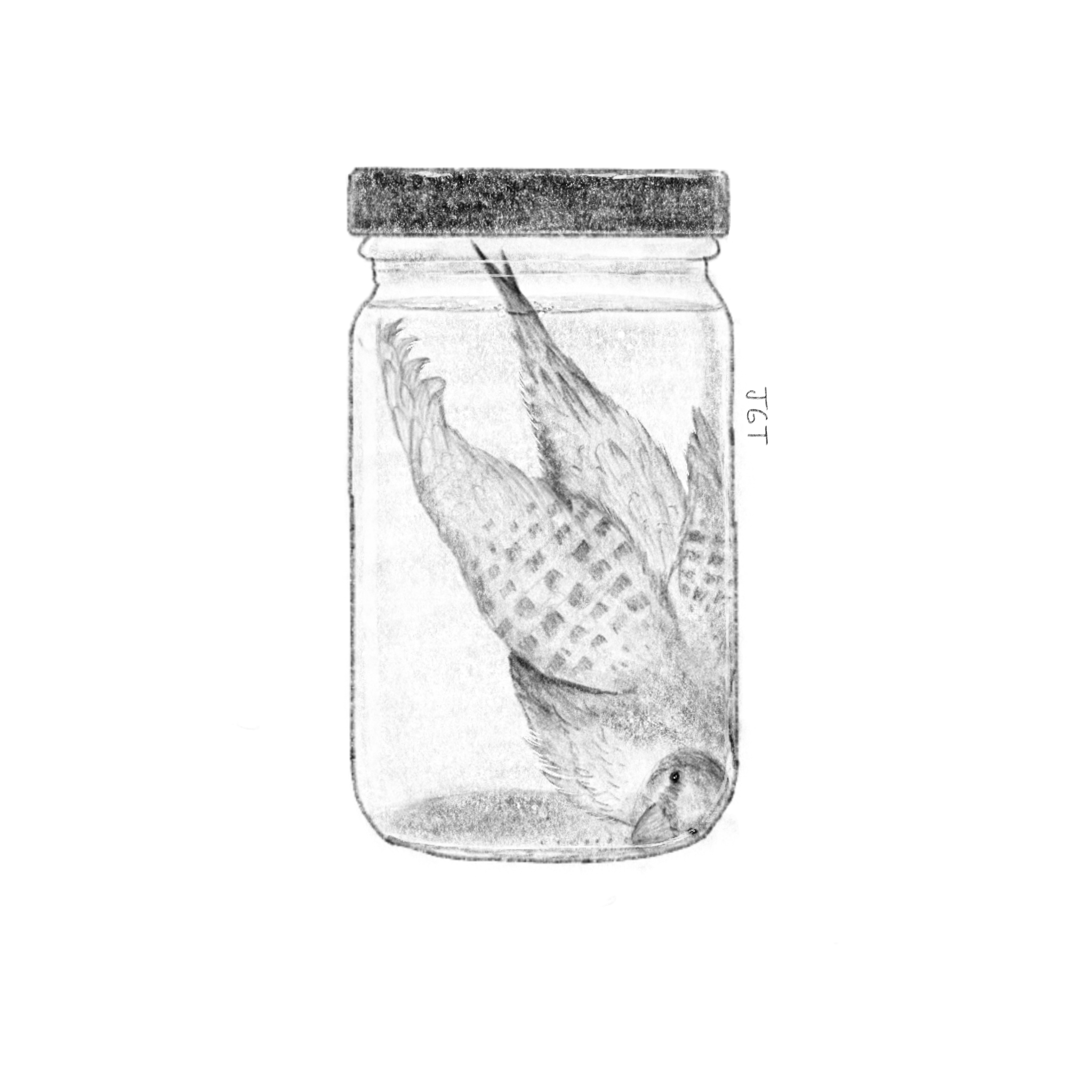

When I was eleven, R & I saw a bird crash into the glass of our classroom window. We took some tri-fold paper towels from the bathroom, rolled its stiff body into a makeshift cradle, and carried it, still warm, into the sixth grade laboratory. Our teacher, not wanting us to confront the loneliness of a gravesite, placed the bird in a specimen jar and filled it with formaldehyde. The smell made us dizzy. The teacher placed a piece of masking tape over the lid, and handed us a sharpie. Name it, she said.

AI: In your work, you talk a lot about diagnosis as a way to create or cultivate personhood. Could you elaborate on what you mean by that?

LM: A clinical diagnosis has all of these expectations of personhood. You can’t think about a diagnosis like schizophrenia without having a whole bunch of expectations of what kinds of symptoms someone with schizophrenia is likely to manifest. You're talking about a disease profile that actually has changed dramatically over the last hundred years. In the early 20th century, schizophrenia was largely racialized white and gendered female, and was characterized by a kind of apathetic withdrawal. In the middle of the 20th century, that completely changed. Schizophrenia became racialized Black, gendered masculine, and now characterized by aggression. The paradigmatic image of who received that diagnosis looks very different.

AI: There’s an idea in the world of psychotherapy that chatbots use cognitive behavioral therapy as their preferred method of treatment, because it's easier for a computer to ‘think’ in terms of beliefs and corrections to beliefs than in psychodynamic psychotherapy’s fluid narratives. If diagnosis is a form of classification, it also seems to be a process that trains your mind to think mechanically. How do you square that with its essential human-ness?

LM: There’s so much narrative contained within what we now think of as diagnosis. Contemporary case studies are these long narrative histories of people’s childhoods, who their parents were, where they grew up, their exposures to this, that, or the other. Prior to the 19th and 20th century, those case studies were much shorter and much less robust. What’s the etiology? What’s the prognosis? Diagnosis had a more causal logic to it. But my disposition, as a historian and a narrativist, is to want more explanation. I think of our humanity as interwoven with itself. Diagnosis is not just a singular thing that confers legibility on one’s entire experience, but rather diagnoses often coincide with one another, and act in mutually informative ways.

ACT IV: THE CULT OF DIAGNOSIS

During the process of editing this conversation, I received a diagnosis of my own. I found myself returning to her words solipsistically and cyclically. I looked, somewhat desperately, for an answer – an errant declaration that would resolve the infirmity of the term ‘diagnosis.’ Almost as if, in finding a definition to diagnosis as such, I could find an answer to who I was under this I could address the burgeoning uncertainty that was bubbling up inside of me. I grew frustrated with the uncertainty of the term, and our inability to define it during the conversation.

AI: That dovetails into my next question, which is about this idea of diagnosis as something that has the end goal of improvement that you speak about in your work. How do you see that goal shifting and changing throughout history? How has the definition of a ‘well’ person changed over time?

LM: Freud famously said that the goal of psychotherapy was trying to transform hysterical misery into ordinary unhappiness. That’s so different from the promise of 2025 – who would settle for ordinary unhappiness? That’s not what the market is about. The generous version is that psychotherapy is about sustained well being. The less generous version is that wellbeing is an epiphanic euphoria, which isn’t possible. It’s the equivalent of being at Coachella on drugs, like lightning in a bottle – that’s the affect that’s suggested.

LM: In America, we’ve always believed that the pursuit of happiness was theoretically possible in this country. But Freud thought that we were over-promising.

AI: Do you see this idea of diagnosis as solely a cultural phenomenon? Or is it psychological, maybe evolutionary, or even epistemological? How do you view it?

LM: There’s certainly an evolutionary component. There’s a value in understanding that something is wrong, and trying to correct that problem. There's a tiger over there, and I can correct that problem by running. My foot hurts, and if I wrap up the wound, it stops hurting, and it also seems to stop bleeding, and that seems to be better. In some way, diagnosis is part of some survival of the fittest mechanism. I’m not an evolutionary biologist, but I assume that those who felt pain and said, “I’m just going to lie here and see what happens” — are probably not our ancestors that survived.

I think we are living in a world now that is also very diagnostically obsessed, and that is exacerbating and amplifying whatever more natural tendencies we might have as a species.

I was at a wedding and someone who wasn’t familiar with my work mentioned the New York Times ‘Diagnosis’ column, where an author explains a patient’s confusing problem and follows doctors until a diagnosis is made. They asked me if I’d read it, and I said, no, I wasn’t familiar with that work. Then they mentioned that this week, the author had gone through the whole article and there wasn’t a diagnosis. And this person felt completely wrong– what’s the point in writing a column about diagnosis, and there’s no diagnosis? What’s the point? And I wanted to say, like, isn’t that life, isn’t that mortality, isn’t that existential phenomena all the time? How often do we actually get a diagnosis?

ACT V: DIAGNOSIS AS A LEAP OF FAITH

In Genesis, God asks Abraham to sacrifice his only son, Isaac, at the top of the mountains of Jerusalem. On the peak, he lays down the wood, makes an altar, binds his son Isaac, and stretches his hand out with the knife towards his beloved’s pulsing, patient body when God calls down – Wait!! Abraham, mid-breath, pauses dutifully. God explains that Abraham had passed the test – he was faithful (for faith, see: obedience, trust, virtue, reason, belief, emotion, hope, God).

In return, God makes a promise: “blessing I will bless you, and multiplying I will multiply your descendants as the stars of the heaven and as the sand which is on the seashore,” God says. “In your seed all the nations of the earth shall be blessed, because you have obeyed My voice.” Neither Mendelman nor I are Christians. But, I can see the way that diagnosis demands that sort of obedient faith – asking the believer to sacrifice their beloved at its altar, promising the possibility of infinite blessings.

AI: Are you referring to a response to the mass doubting of science we’ve seen in the last ten years, when you say that diagnosis requires faith? Or are you referring to a more devotional leap, sort of like the way we have faith in God?

LM: Yes, both — I think that they're related. Science is a religion, science is a leap of faith, because there's so much you can't see and you can't know. I grew up in a household with two scientists– my parents– and that was not a religious household, beyond, as I have come to realize, a deep faith in science. For me, science remains the kind of faith that I can sign up for, even though I've had a really raw, poignant exposure to clinicians as very fallible human beings.

You can get it right every time in theory, and then humans enter the room and all of a sudden, surgeons make errors. Residents overlook something. The report doesn't get read correctly, like it's riddled with human error, not necessarily out of any kind of malevolence on the part of those people, right? Just because we're all human and we make those kinds of mistakes.

AI: You mentioned a personal experience with the fallibility of clinicians. Would you be comfortable speaking more about that?

LM: My mother, who was an immunologist, died of cancer in March of 2024, after a series of human errors. I saw the thing that I had the most — that we both believed in the most…

Mendelman pauses.

AI: I’m sorry for your loss.

LM: Thank you.

LM: But, that’s the hard part, right? You can’t really avoid medicine. But you also can’t put all your faith in medicine.