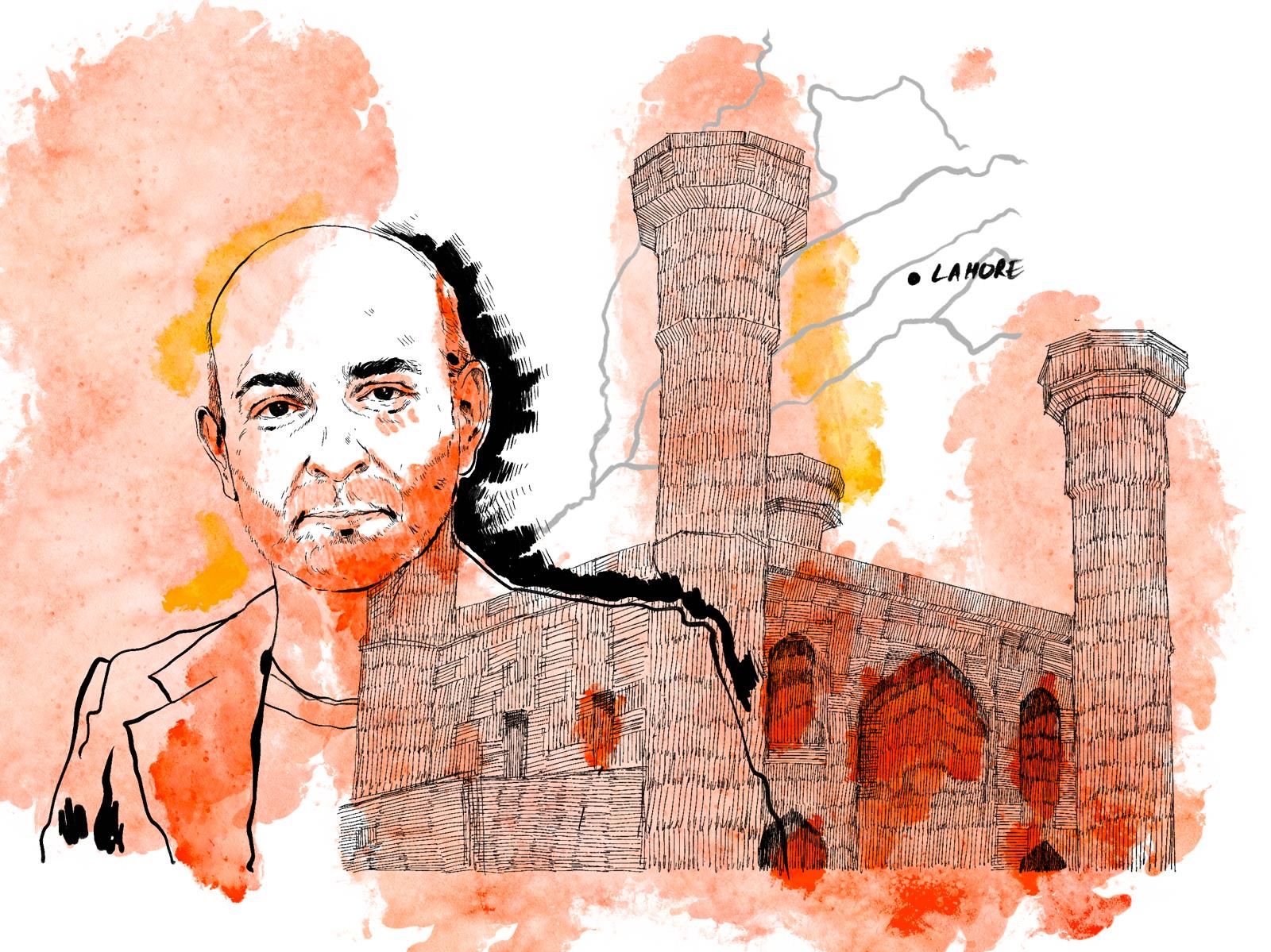

Note: The non-italicized text reflects Mohsin Hamid's words during our conversation in Lahore on August 30th, 2024, while the italicized portions capture my personal musings.

Lahore exists where it is because there are five — or really, six — great rivers in the northwest of the South Asian subcontinent. If you were approaching from Central Asia, as many traders and invaders used to do, you would go from Kabul, cross through into Peshawar, then leave the hills for the plains. As you cross the plains, you would cross these rivers, and find Lahore situated in the middle of the Punjab — the five rivers.

You and I are on the eastern side of the river, the protected side, the side that invaders would have to cross to get to Lahore, if coming from the northwest. On this side, there was a walled city and a fort, and that was old Lahore. As you proceed out from old Lahore, you find older parts of Lahore, and eventually, you get to the British colonial part of Lahore, centered around Mall Road. It has the National College of Arts, where Rudyard Kipling's father was the first principal. Then, as you continue out from there, you come to the older suburbs, like Gulberg, where we are now, which were laid out in the 1950s and 60s. If you keep going, you encounter newer suburbs, places like Defence, which are now getting close to the India border. Lahore is nestled right up against the border with India, and it's historically been a sprawling, flat city on the side of a river but not really facing the river, unlike, say, the Seine flowing through Paris. Lahore has its back to the river, probably because of flooding concerns. There's a canal that runs through it, which is sort of like Lahore's little river, with sprawling suburbs and housing developments. More recently, it's begun to go vertical. Where we are now, near Main Boulevard, you see 20-story buildings, with more and more coming up, along with higher buildings and office towers. We're in what feels like 1960s Lahore—about a half-hour drive from the year 1000 Lahore, but also only about a half-hour drive from 2022 Lahore. The city has grown, in my lifetime, from about 3 million people, to over 12 million today.

I visited Lahore at the end of August. It was hot, of course, but not the kind of hot about which you can commiserate with Lahoris, who’ve seen hotter days. They will smile at your delicate season-bred sensibilities to the climate and tell you to visit the city in December, when the city is chilled without central heating, but heated by the wedding season.

“Baahir se ai hui hoon,” I’d grimace. I’ve come from outside, a common refrain for those who've left the country. I was doing senior thesis research in the Punjab Public Library, the National Archives of Pakistan, and South Asia Resource & Research Center, paging through periodicals crumbling in my hands. The English periodicals weren’t cataloged, but I pleaded with the archivists, rather pathetically: I was a student from America, after all, I’d come all this way to look at the archives, here, I even had a letter from Harvard. This revelation was costly — I was charged 10 rupees per photo I’d taken by the archivists, because I was from baahir, and because I spoke Urdu laden with the linguistic insecurity bespeaking a foreigner — mixing up grammatical structures, intonating incorrect vowel sounds, resorting to English words, far exceeding the acceptable threshold. I wore desi clothes, too, to mask my foreignness, as I embarked on these archival excursions, kurtis that covered my behind, linen pants to offset the heat: outfits that members from my class background no longer seem to wear in Pakistan. It is all ‘Western’ clothes in the East now; my Nani said that desi clothes are “peindu.”

I met with Mohsin the day before my return to Cambridge. I’d off-handedly emailed his agent after reading his Exit West, because I’d cried, and I was startled, by my response, into action. I read Reluctant Fundamentalist on the plane to Lahore, and I remember thinking: how have I not read this before? And then, that bitter-sweet, sinking feeling: he’s said everything I've ever wanted to say, and better!

Mohsin and I met at a restaurant in Gulberg, swanky and well-populated. It was late, maybe around 2 o'clock, but Lahoris were still lunching.

There has been enormous growth in the middle class of Lahore, which includes both migrants from other parts of Pakistan and social mobility within Lahore. When I was growing up, there were a handful of elite schools that most middle class kids went to, and you would often know the people—somebody's family was in this school, your cousin was in that school. Now there are lots and lots of schools, and the Lahore my children are growing up in is much more like a big city where you may have no idea where your best friends are. Their friends are scattered across many different schools.

It has become a more impersonal, bigger, but also in some ways more dynamic city, much more polluted. One of the biggest changes is that the Lahore of my childhood was a Lahore where the winter, from November until March, had gorgeous weather — you'd be outside all the time. But now, not anymore. Now, it's like a Blade Runner-ish, post-apocalyptic situation, with horrific air quality, where you run your air purifiers, and the kids can't go to sports practice, and everyone tries to stay indoors. That's not entirely charming. It has become a big city in both good and bad ways.

Recently, it has been a very difficult time, both economically and politically, not just for Lahore but for all of Pakistan. I can't say that I feel enormously optimistic. But that said, when I travel, people aren't in a very optimistic mood in the UK either, or in the US. So maybe it’s not an optimistic mood anywhere.

I think that it's dangerous to be despondent, because when everyone is despondent, then what emerges is like a politics of reactionary nostalgia. You know, whether that's going back to like Islam of 800 years ago, or going back to like America 100 years ago or Britain 50 years ago: these reactionary nostalgic politics are born out of a sense of despondency. So if we actually want to find a more inclusive, progressive future, we have to be optimistic about the future, and so I try to write novels, which, in their own way, are critically optimistic. Now, that being said, you’ve caught me at a sort of somewhat despondent moment, and why I'm not publishing a novel at this very second.

I think writing a novel is like having to tell your kid: Look, kid, you're gonna die. That's just how it is. We're all dead, you know. You know it's true, but maybe not the best mode of parenting. If it is, I don't know, it's just not how I parent. But if you sort of say, look, there's amazing beauty and truth and interesting things possible while we are here for a temporary time — that feels like a better stance than that. Similarly, there's so much desperately wrong with the world that is heading into terrible directions, and yet: there is the possibility for better things to happen.

It's not to say, Oh, if we do nothing, it's all going to be fine., but rather, if we do something, it's possible that things can get better. And that kind of critical optimism, I think, is useful. It comes back in a way to these Gaza protests right on us. Are they really doing anything for foreign policy? Who knows.

People are trying to shape the future that requires a certain degree of optimism, and it's only because of that kind of optimism on not just the Gaza protest, but a million different other things, that change happens. So for me, that position of critical optimism is essential. Really. The alternative is just a reactionary, ‘might makes right.’

I've been reading a lot about the "brain drain" crisis and how it's been reported that 700,000 people left Pakistan this past year. The destinations are telling; lower to middle-class, single men, fly to the Gulf, where initiatives like the Saudi Vision 2030 demand labor, so much labor, that the trickle to these states has reliably increased. The elite, on the other hand, debate which American and British and Canadian colleges to send their kids to. Harvard kids bemoan the “brain drain” matriculation to careers in finance and consulting, but in Pakistan, it is the hordes of people eager, anxious, to leave the country. There’s no civil war, no dire or desperate impetus for this exodus.

While I was in Lahore, my family said much of the same: nazar na lage, we are so proud you are studying at Harvard, stay in America, what is there for you to do in Pakistan, why are you writing about our country for your thesis? Write about America instead.

Well, there are two things I will say. The first is that when I moved back to Lahore in 2009 from London, it was a difficult moment politically. Around the time of Benazir's assassination, the restoration of democracy after the Musharraf period, the lawyers' movement—there was a lot happening. But we had a considerable degree of free expression in Pakistan. We have nothing like free expression in Pakistan today. It has been a very sad trajectory, and today we live in a society that is enormously restrictive of speech. It's been growing that way for a long time, but it has reached its highest degree more recently.

Now, of course, in 1980s Pakistan under dictator General Zia-ul-Haq, we had very restricted speech. But then with the arrival of satellite dishes, the period of democracy in the 1990s, the Musharraf government—which was actually quite pro-free speech even though it was a dictatorship—there was a 20-year period of opening up. Now we have seen, over the last 15 years, a period of closing down, which coincided with my return here. The vibrant sort of self-criticism and critique is much less, which creates its own sort of mood. I have always thought that one of the things that saved Pakistan from a fate like Iraq or Syria—countries that are totally driven by civil wars—is that in Pakistan, we didn't just have an all-powerful dictatorship. We had moments of dictatorship interspersed with moments of democracy or semi-democracy. We had imperfectly functioning but somewhat functioning courts, media, etc. I think moving away from that makes us a more fragile society. So, I'm not feeling particularly optimistic, but that said, it's just a blink in history, and things could change. Things might change dramatically, but at the moment, most people I talk to feel utterly despondent. They feel they can't articulate their thoughts politically, and they feel economically like the country is stuck.

My first book of Mohsin’s was Exit West; I was told I would like it because it was by a Pakistani and about refugees (don’t ask). Turns out, I really did like it, and so I read The Last White Man next, about a white man who wakes up many pigments darker. Moth Smoke, The Reluctant Fundamentalist, and How to be Filthy Rich in Rising Asia followed, thematically ranging from 9/11 and racial politics, class struggles and doomed romantic relationships. Two of the books take place in Lahore, and the rest draw some kind of inspiration from Lahore. Mohsin has made a really compelling case for Lahore’s promotion to the ranks of City-hood, akin to New York City and London, due to their cosmopolitan characters and layered histories. “Lahore, Lahore Hai,” Lahoris say: Lahore’s Lahore.

I think the country is stuck in a way, because you can imagine two paradigms for how to build an economy. One paradigm is the one we've been told in Pakistan to follow, which is this geoeconomics idea—that our location is our asset. We leverage our position into some kind of economic gain, which is really a rentier model. I don't think that has worked particularly well. The other model would be to focus on the people. The amazing thing about the people is that Pakistan keeps producing a huge pool of very talented, hardworking, creative people, and it takes enormous mismanagement to prevent them from having a very successful country. But we have mismanaged ourselves.

Our driver’s son has just completed a bachelor's in computer science and is looking for a tech job. Lahore is a place where lots of people go to university. I think the statistic is that more than 300,000 students are enrolled at universities in Lahore today, which is a number probably as big or maybe even bigger than Boston. These people come out into the world, and if we had a system in place where we allowed them to flourish, I think we'd be doing great, but we don't. As you say, many of them desperately want to leave. I don't have much hair —but the guy who used to cut my hair for years moved to Canada. He's there now. This brain drain is an immense waste of potential. So, I'm not saying that people shouldn't leave; everyone has the right to look for a better life. But I'm saying it's a real shame that a place like Lahore, which could be so much more than it is, is letting that potential slip away.

Ezra Klein said he imagined Mohsin’s The Last White Man to be taking place in Scandinavian countries, based on the names of the protagonists. Mohsin did something similar in Exit West and How To Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia — blurring the features of character and place. Still, identifying features make themselves evident to the reader, irrespective of the valiant attempt to obscure. The city in Filthy Rich, for example, feels distinctly like Lahore, despite Mohsin’s deliberate veiling of its identity.

My sense is that readers make novels in concert with writers. And in a way, I tend to try to write novels that give space for readers to make it up. The way this works is that, you know, I'll go into an interview and somebody will say, "Why did you decide to set this novel in the United States?" or, "Why is it set in Sweden?" or, you know... And I'm like, "You know, this is set in the UK, isn't it?" What's happening is each reader is making their own novel, and they each make different novels.

And so I try to write novels that give a lot of space for readers to do that. Just enough imaginative strokes that there's something for the reader to build on, but lots of space. In Exit West, Saeed's mother is killed, and the book talks about his mother, but his mother doesn't have a name. Now, what function does that serve by not naming her?

If it was a mother whose name was my mother's name, then that wouldn't be your mother's name; it would just be this particular character who has died. But when it's "his mother" who has died, it is almost natural for you to impart that word with what you understand a mother to be, which is, of course, influenced by who your mother is. And so it has a different weight, that death.

Pakistan seems to have split in half: the upper class is patriotic to itself, allegiant to those who exist in the same circles, to the West; and the poor masses are outside of this, an ‘imposition’ on the wealthy, the victims of unnamed issues.

Murad Bacha, from Mohsin’s Moth Smoke, says: "People are fed up with subsisting on the droppings of the rich. The time's ripe for revolution." In The Last White Man, Anders the protagonist posits a Robin Hood paradigm: "It is a poor person's right to skim money." The money in question is his own.

Pakistanis are always prophesying the death of our country, but I’m convinced that Murad Bacha’s Parasite-esque revolution is near.

When I came back to Pakistan at the age of nine in 1980, I remember seeing a cleaning lady at my grandfather's house. And I could tell this person is different from us. You know, she looks different, she dresses differently, she speaks differently; her demeanor is very different. She's not one of the family. I remember turning to my mom and saying, you know, my parents, and saying, "Is she a slave?" "No, it's not a slave, like a servant." And I was like, "Oh, okay." But coming from the States, I didn't know what a servant was, and I could only associate in my imagination. My natural thing was, "This is some person who's like an enslaved person, right? Like, why are they acting so differently? Why are they being treated like this?"

And so that encounter of a partly Americanized consciousness with this Pakistani reality has always stayed with me. And I guess I've just been attuned to class. But then on top of that, I think having lived in different places and become a kind of chameleon as a kid—how do I fit in? Wherever I go, to fit in, you have to observe quite closely, right? If, you're going to be a green lizard on a green wall, you have to know that the wall is green.

So you very quickly begin to read the way class functions. You know, here in Lahore, in New York City, at Harvard College, for example. And so I became very interested in this, as both an insider and an outsider. You know, somebody who, at various times, has been an elite, and also on the outside, arriving in California as a foreigner, becoming kind of a Californian kid, returning to Pakistan as a foreigner, becoming a Pakistani kid, going to the States, having this elite job, then after 9/11 being this weirdly othered — and then, kind of a feared — person. So being on both sides of these divides has made me very attuned to it.

So I look at class, very aware that it has been constructed, that this isn't the innate way of things. We have made these structures. There's no reason why I went to Harvard, and somebody else is serving us coffee right now. Some system exists that allowed that to occur. Not that I'm saying there's no free will, and there's no difference in, you know, somebody's ability or work ethic, but those things occur inside a much more powerful systemic structure. So I write about that.

Changez, protagonist of The Reluctant Fundamentalist, describes himself as a member class of professionals with dwindling wealth, and how the decline of wealth in Pakistan is far outstripping the pace at which status is declining.

It’s kind of true. My Dada is a member of a ‘country club’ — for which there is a robust ecosystem in urban Pakistan — called Gymkhana. I’m pretty sure his loyalty to Gymkhana far surpasses that of Lahore, or even Pakistan. I spent many days of my childhood summers and winters in this club, which has changed much over the span of my life, allowing for more Pakistanis, of different family and class backgrounds to join, about which my Dada grumbles. Now, as an nearly-minted American citizen, armed to the teeth with my democratic self-righteousness, I find myself offended by these clubs.

Yup. All these clubs that non-White members couldn't belong to until, like, 1947.

I think that, increasingly, money is coming to be a stand-in for social class, not just here, but everywhere. So, you know, whatever the norms of how a billionaire was supposed to conduct themselves in the US up until recently, you know, are now gone, right? And the sort of crass "I have the power, I can do what I want. I'm gonna tell Harvard what to do. I'm gonna tell the country what to do. I'm gonna tell you what to do." This is new, right. And there are a lot of people who were not ancestral billionaires. They are self made billionaires, right? And they are the new power class in the United States. Well, something similar is happening [in Pakistan], whether it is somebody who's risen up in the military or in the bureaucracy or in, you know, in the private sector, or whatever, how people have made their money, they made it, and then they have this power. And so I think, I think all over the world, we're seeing old class hierarchies, you know, being upended, not replaced with a more egalitarian society, but with new class hierarchy, obviously. And I think one of the things that I suppose is quite interesting is, you know, we imagine that power acts from a class privileged position, let's say, in the US to a class unprivileged position in Pakistan. But actually it's much more complicated than that.

In fact, if one perceives one’s class position as very vulnerable, that results in all sorts of things. Like Osama bin Laden was a very weird guy, you know? Why was he so incensed by what he saw? So many of the sort of 9/11 and post 9/11 actors that we read about were upper middle class or wealthy people. Think about the US War of Independence: a lot of these were like slave owning gazillionaires from their time, rising up against Britain. Like, these Thomas Jefferson type figures, even George Washington? These weren't like the poor peasants. They weren't, you know, Ho Chi Minh. They were, in a sense, upper class Americans. So oftentimes, in the contest between cultures, ideas, and society, what we're actually seeing is a displaced upper class, or a slighted upper class, or an upper middle class jousting for power. And so we see that in Pakistan too. And part of the tension between the clerical-minded, religious-minded power base in Pakistan, and a more secular-minded power base in Pakistan, is the unresolved conflict of two sets of elites, deciding which is the real elite. So I think when you start looking for this stuff similarly, in the US, in the conflict between the cultural elite of newspaper writers and the money elite, there are two different elites that are in contest. And so they have different cultural values. And for me — not quite like an insider in any of them — but a semi participant in many of them, I feel like I write from a sort of insider-outsider standpoint.

More on Changez: he describes his White interlocutor — with whom he dialogues, for the entirety of the Lahore-based novella — as having that foreigner’s feeling of being watched. I’ve painfully experienced the same: a few days earlier, I was sitting in my grandparent’s car, just a few miles away from the restaurant at which I met Mohsin. A woman selling hair ties knocked on the window, and I rolled it down to give her some money, and she said: Yeah, you should be giving me dollars, because you're not from here.

And I hadn't said a word. Normally, when I’m shopping with my Nani at bargaining markets like Liberty, my Nani will hiss at me not to speak English. I got that. But based on nothing — just my person — she’d discerned my foreignness. I was awed by her canny, the accuracy of her foreign-dar, reaching this conclusion from so little.

In a sense, you’re one of the ones who was fortunate enough to get up and out, and you made it. And then you come back here, all rich, and people want a piece of that.

I don't know if they even think of you actually, as a foreigner, exactly, but in the sense that within the category of people from Pakistan, there are those who got out and made lots of money, and those who didn't. So are you a foreigner?

Or are you the really rich cousin who left — you're just like the rest of us, but you have a lot more money because you got out and the others didn't. I’m not sure exactly what it is, but certainly there is that thing where some people in Pakistan have been elevated to this saintly class of foreign passport holder. Others are still living the benighted life of being unable to leave. My former hairdresser is now fortunate to be in Thailand, and my current hairdresser is stuck here.

So there is that now, but there is also, of course, the whole idea of Whiteness, because there are many different skin colors in Pakistan. You know, in my own family, there are people who look White, people who look dark — we have everything.

It isn't exactly racial, but it is also not entirely neutral, right? It's not, oh, this person is a white person, and this person is brown, because they're all Pakistanis. But on the other hand, there is a certain plus to being lighter skin: a pigmentocracy. So it's very confusing. You know, it's not exactly the American understanding of race, but it's also not like, Oh, it doesn't make a difference. It does make a difference, but it's not race. What is it?

It’s a bit like you're foreign, like you have a second passport, to see somebody who would pass as White in the United States — but it's just a Pakistani and Pakistan. But it also has advantages to having light skin, in the American context, and that complicates how we think of these things, what the imaginary is. Now, would they have those advantages if we hadn't had a colonial history and invaders coming? Maybe, if we had always been invaded from south to the north, and the powerful people were Southerners, we’d have the exact opposite pigmentocracy, but we don't. It leads to this position of being able to feel that there isn't just one way of imagining things, and that the American imaginary on race is not the only one. What is Pakistani is kind of an interesting question. You know, am I a foreigner or not? All of these things are all wide open and so they're worth exploring, partly because one is trying to figure out what one thinks. You know, what do you think about the situation? Who knows?

Well, write a novel, and see if you can figure it out.