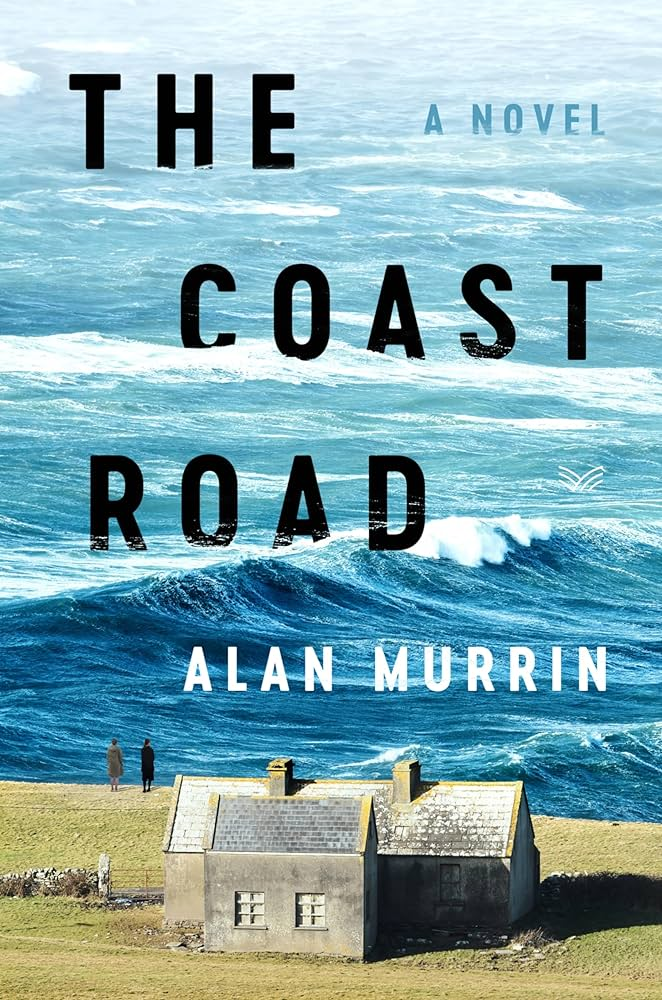

Two tiny women stand on the edge of a cliff, almost hidden, looking out at the oceanic expanse on the cover of Alan Murrin’s debut novel, The Coast Road. The ocean is overwhelming. These diminutive figures are Izzy and Collette, two women living in Ardglas, a small seaside town in Northwest Ireland.

Something bad is going to happen, we know this early on. In the prologue, Izzy speaks to the detective, who asks her about a recent fire that had happened in town. He wants to know how, when she saw it from across the home in the bay, she knew it was set intentionally. Izzy’s response? “That’s another story altogether.”

“The Coast Road” provides a triptych of marital life in Ardglas. Izzy and her husband have fallen into a rut of fighting and making up, fighting and making up. This pattern gets upset by Collette, a “blow-in” (read: out of towner) married to wealthy Shaun Crowley. Having recently left Shaun to move to Dublin with her married-man lover, Colette is back. She manages to find a tiny cottage to rent, owned by Dolores Mullen, who is struggling with her adulterous husband. Following these women’s lives, Murrin paints an entertaining, though not dazzling, portrait of marriage in 1990s Ireland.

Murrin’s Ardglass is brimming with life. He describes the one Main Street and the town’s main throughway, the eponymous “Coast Road.” As Izzy drives home one night, she describes the road, where “hills rose up on one side and tumbled down into the Atlantic on the other” with “the moon hanging low over the bay looked like someone had pared a sliver off it with a knife.” We learn that it’s a place blooming with new money, thanks to the lucrative fishing business, helped along by Izzy’s politician husband. Everyone knows one another — Izzy sits in a packed church, and gossip spreads like wildfire.

Though Murrin paints a bustling community in Ardglas, the potpourri of characters does not allow for us to get close to any of them. The book flits through perspectives, attempting an ethnography of the edge of the 21st century in Ardglas. The reader feels like they have met everyone, but gotten to know no one. It’s hard to connect to one voice.

Because of this, Murrin’s characterizations are weaker than expected. Izzy, who is established as a sort of quiet and demure character, is suddenly and shockingly described as witty, halfway through the novel –sure, she might make a few cracks to Father Brian, but nothing that could reasonably be thought of as witty. Murrin’s structure does not allow us to sit with characters, making every personality trait a revelation, rather than the slow understanding of natural kinship.

The real draw of the book, however, lies in its setting – the world of Irish relationships in a country where divorce hasn’t been legalized. Until 1995, most Irish marriages lived in something worse than the terrible ambiguity of the modern situationship. Murrin shows that a community without divorce is far from a world with only perfect, intact marriages. Though couples could go through the process of “legal separation,” it was taboo. Izzy, Colette, and Dolores explore the pains couples might take to avoid the murky waters of undefined relationships. This couldn’t be further from reality in the US, where almost 50% of American marriages end in divorce.

At the end of the story, Ireland is just on the cusp of the referendum that would lead to legalizing divorce. The margin of the referendum would be razor thin, with roughly 10,000 votes deciding the result. But once I finished the novel, I was still left wondering why the referendum mattered to the story. Though it was often mentioned, it didn’t seem to shape how the characters’ saw their own relationships. In fact, it often felt like their relational issues existed separately to the referendum – had divorce been legalized, I’d imagine they were doing the same thing. Murrin seems to be grasping at a bigger message, something decisive about divorce and marriage and gender in Ireland, that seems to be lost amidst the turbulent lives of the novel’s characters.