Inside the Mexican restaurant, a blonde Polish waiter withdrew the contents of his pockets onto the marble counter, and these included a yellow lighter, loose change, a leather keychain with its flimsy metal token inscribed “mammoth cave, kentucky,” and, at last, an iPhone charger, frayed at the end with its internal wires exposed. He inspected it for a second, frowning. This was Avenue A and it was nighttime. Sitting out on the patio facing Tompkins Square Park was the lone customer, a boy named Alonso.

Alonso thought that this Mexican restaurant patio could very well be his day’s final stop. If true, it would terminate a series, all those stops, situations, and stations that had constituted his day, beads on a string pulled into the future: first the hairdresser’s bedroom where he’d woken up and had sex with the hairdresser, then Lexington Ave where he and the hairdresser had walked and eaten a bagel together and where he’d caught the Q train, then the fry cook’s living room where he’d watched reality tv with the fry cook before the fry cook left for work, then the fry cook’s fire escape from which he’d watched the very same fry cook rush towards the train station in a light drizzle, where he’d watched his own feet dangle high above the street and watched the gleaming, brand-new cars shoot beneath the dirty soles of his sneakers and felt that this really was the atmosphere in Manhattan, everything and everyone trying to look new, shiny, and clean as they flitted about beneath a dirty, stinking shoe. A few more stops and he’d ended up here, on this patio, Avenue A, and it was close to one in the morning, the street empty, and the tall blonde waiter came up behind him, a shadow moving against the white wall, asking if he wanted anything, and he said, no, he was okay, but then said, wait, I’ll get an empanada, another pork one, and the waiter asked him if he wanted another drink, and he said, no, that’s okay, and then the waiter, with an air of bashfulness, asked him if he possibly had an iPhone charger handy, and he said he was sorry but he didn’t, and then the waiter told him that he wouldn’t normally have asked a customer for a charger, but that these were special circumstances since his sister, who had just emigrated from Poland, was in the hospital in Queens with appendicitis and that his phone had died just as he was getting an update on her condition from their cousin. Alonso, upset by this, didn’t have anything better to do so he offered to go over to the 7-Eleven and buy the waiter a charger if the waiter could give him some cash to do so. Then the waiter handed him a twenty and Alonso walked through the barren street to the 7-Eleven. Its clean neon sign was visible from far away.

When he got to the store there were just a couple of construction workers inside and he surveyed the shelves for chargers. The man behind the counter was half-asleep, lulled by talk radio. Suddenly the door opened and five figures entered, each of them wearing a small blue sailor’s hat made of folded construction paper or card stock. One was very tall and husky, a man in a white button-down and black sweatpants who walked right over to the back fridge with a strange, luxuriant, swaying gait, took out three one-liter bottles of Sprite, and then walked straight back to the counter, the rest of the group standing around silently in the front of the store. One of them was a girl Alonso’s age with curly black hair and a Glen Campbell t-shirt. Her eyes met his for a moment, but then he aimed them back down to the store’s dirty black rug. The group left just as quickly as they’d come, and Alonso didn’t want to linger so he bought the charger and a granola bar with the twenty-dollar bill that the waiter had given him and he went out the door and trailed the group at a safe distance.

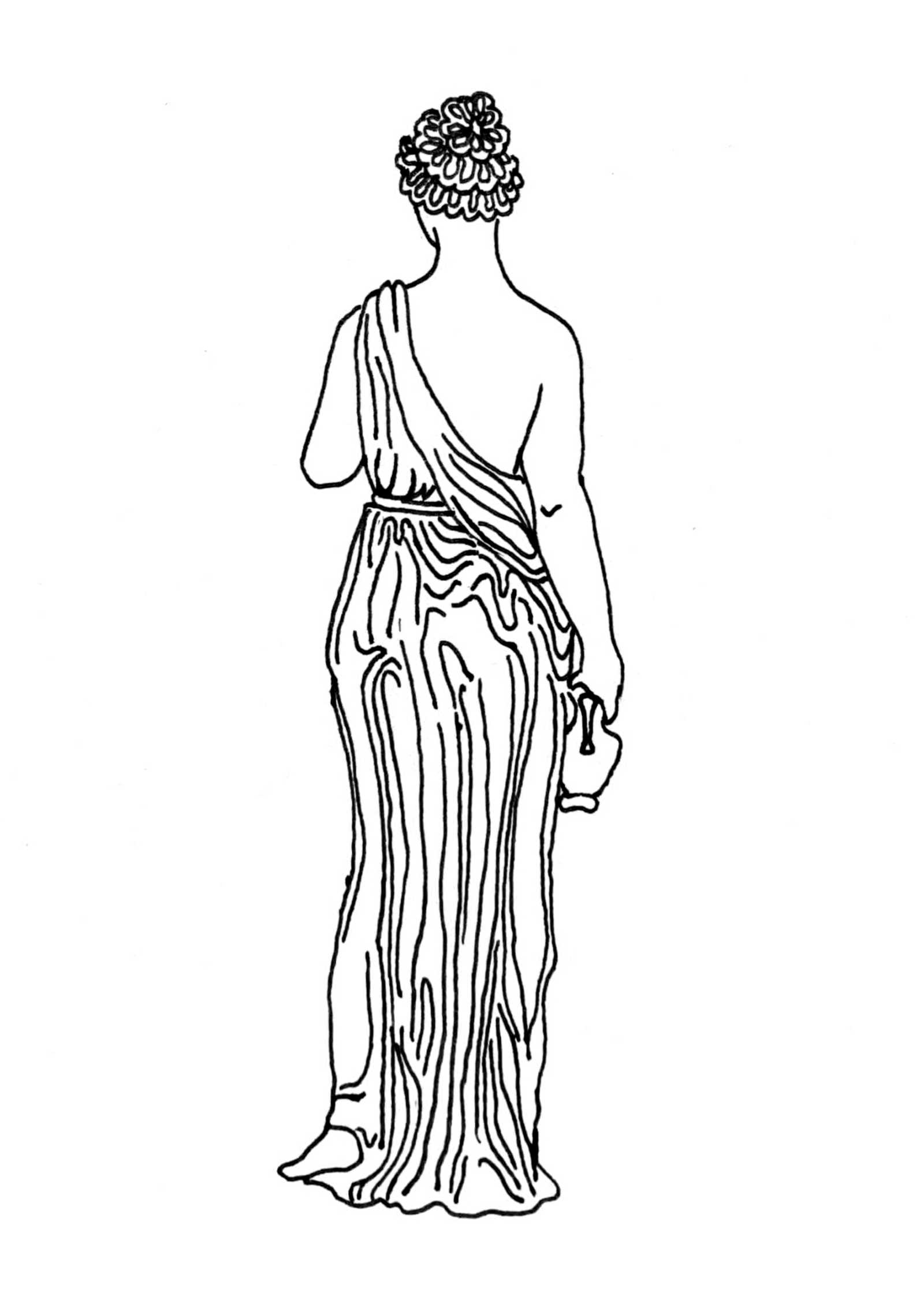

They stopped at the marble pavilion in the park, which was a Roman-style monument with a drinking fountain inside, and on the top was a bronze statue of a toga-wearing goddess (Hebe, with a goblet in her hand) and the word “TEMPERANCE” inscribed into the marble along the rim of the roof below her. Ten blue-hats were mulling around near the pavilion, and the tall man was sitting near the middle with one leg inside the pavilion and the other leg languidly resting two steps lower, and in this way he leaned his back against a column and unpacked the plastic bag full of Sprite bottles and rested them one-by-one on the ground. Off to the side of the group were two hatless onlookers, a young woman in a pantsuit and an old, fat man with a yellowing beard and extremely round, small-lensed glasses that made him look like a character in a Victorian novel. Alonso, not yet bored, stood next to these two and waited with his arms crossed. It wasn’t long before another blue-hat arrived, his arrival slowed by a large, unshapely black object that he pushed, or wheeled, in front of him, up to the pavilion and then, with some difficulty and care, up the two marble steps, and there in the dark of the pavilion center beside the fountain, he unzipped it from top-to-bottom and it was revealed to be a harp, gold and white with flashes of red on certain strings, and the man also produced a small, flat piece of black plastic from the inside of the harp case, and this turned out to be a foldable stool. At this point, the other blue-hats arranged themselves into a little formation or audience facing the pavilion and its harp.

The tall man began to speak in a high-pitched, neurotic voice, welcoming everyone to the gathering, informing them that it was, of course, the monthly assembly of the Metropolitan Society for Dream Inquest, and that every part of the assembly would follow the visions and prophecies of the society’s two founders, Cutty and Winnie Fisher, who recorded free jazz music and published instructional dream manuals from their apartment in Red Hook between the years 1961 and 1978. The society, he said, holds as its central tenet the notion that dreams persist after the death of the dreamer. He elaborated no further and there was a lengthy silence. Then he explained that on this night the goal of the assembly was an “audition,” and that candidates would each play a piece on Winnie Fisher’s chromatic harp. Whoever demonstrated the requisite “level” would become the society’s official harpist and receive an annual stipend in return for a small number of appearances. The society’s previous harpist, he said, had moved to the Maldives.

First up, he said, was Craig Günther, who played first seat in the New York Harp Ensemble. The old man with the round glasses and the yellow beard stepped forward out of the place where he had been standing next to Alonso and walked over to the harp. His facial features disappeared in the darkness of the pavilion. He took three deep breaths and then launched into something like Bach, his body moving fluidly with the song, back-and-forth, and his fingers, seen at certain angles on the transparent strings (refracting the light of the park’s streetlamps behind), walked or jumped or danced along like water insects. Sometimes, one or both of his hands would drop from the instrument during a rest and float back up again. When he’d finished, there was scattered clapping. He stood up and took his spot back in the line-up next to Alonso. He wiped his brow with a handkerchief.

Next was the young woman in the pantsuit, who was introduced by the tall man as Natasha Thornwood of Harlem’s Absence Chamber Group (ACG), and she took her place on the stool and put her hair back with a green scrunchie and then began to play. The notes were sparse at first, plucky and close together in the middle-range of the instrument, and when she played them she seemed to pull with all her might, her elbows darting outwards with vigor. Gradually the song, significantly more experimental than Günther’s, perhaps even improvised, built outwards in both directions, up and down on the strings, until the notes were streaming across the full range in reams, teetering on the edge of dissonance, veering into blues. Finally, her hands landed on the highest and lowest extremes of the instrument, creating an ambience that sounded like a thin, silver net over a vast chasm. She bowed and there was a storm of clapping.

At this point, Alonso had already considered leaving. Or should he move to the side? Would they consider him another candidate? As the clapping died down he looked at the harp sitting there in the cold darkness of the pavilion. There was something unusual about seeing such an object in Tompkins, which was otherwise a kind of armpit of the city, a nexus of Manhattan’s lost or aspiring-lost. The harp was so large, dwarfing the fountain, filling the pavilion with a certain grace or fullness that it had never seen before. It was an alien grace, parabolic in shape and ancient, imperial in color. How many had played it? Heard it? And yet, it was there, right in front of all of them, ready to be touched once again. The tall man began to speak again, but Alonso, his eyes transfixed on the object, heard only a kind of rhetorical sound, the sound of ceremony itself, the movement from one communicative event to the next, and he raised his voice and said, I am here to play too, interrupting the man, but the man was obliging, and he asked the boy for his name, and asked the boy if he had anything to share about his background with the instrument, and the boy said his name and then said no, not really, and then the man said okay, but he said it strangely, as if something were wrong, and then the boy interrupted the silence and said, I do have something to share. My mother is a harpist, he said. I was raised by a harpist.

He walked over to the pavilion now, but before touching the harp he went over to the fountain and had a drink. Then he moved the black bench off to the side and cradled the harp standing up, the instrument coming to his mid-chest, and he touched the strings silently, feeling their texture and tension, and then he played a single note, the lowest note on the instrument, a red string with a plump, round sound. After some silence he played this note again, and played it over and over, his mind completely set on the sound of this note while his other hand began to mindlessly search the upper regions of the instrument, the shortest and highest notes, across which he dragged his fingernail producing a dry sound. And then he began to moan and laugh, all the while playing the single lowest note again and again with his one hand, and then he began to tap on the wood of the instrument with his other hand, striking it in irregular ways, rapping on it, oscillating between delicacy and aggression. And then, all of the sudden, he stopped, set the instrument down, and then tried to bow but was overcome with laughter and found it difficult to finish the bow, so he simply took his hands and put them on his shaved head and looked out at the crowd with a smile.

The applause was immense, roaring.

The tall man walked to the back of the crowd of blue-hats and bent over to speak briefly with another man who was seated in a wheelchair. He walked back towards the pavilion with his easy, lurching walk and said that although he and the other board-members of the society were surprised by the unforeseen progression of the night, the notion of the unforeseen had been a fundamental interest of Winnie Fisher and her husband, and that, for this reason, they had decided to offer the position to Alonso, who had demonstrated his level to be far more than adequate.

The boy had already turned away. He was looking at the fountain and then out into the park where there wasn’t a single blue-hat, where there was only the empty night, full of space. In an instant he reached back and pushed the instrument with his sticky palm, felt it swing outwards, out towards the blue-hats, and he launched away into a sprint, barely hearing the crash of wood and fiber against marble and concrete, the single twisted shriek of the harp’s defunction, barely hearing the voices and shouts over the wind in his ears and the beating of his heart.

Without looking back once, he darted out of the park, across the street, and into the restaurant. The blonde waiter looked up, surprised. The boy pulled the coiled charger out of his pocket. Do you have somewhere I can sleep? said the boy. What? said the waiter. I need somewhere to sleep. The waiter fumbled with the new charger, uncoiling it. There’s a small futon in the back, he said. But you’ll have to get out by six. That’s fine, said the boy. Show me.