Fall 2022 Issue - The Harvard Advocate

Poetry • Fall 2022

They wake me. Like car alarms bleating along an empty

block. How many beloveds in me whom now I survive?

Even Forough must have run her loving hands to water.

My lips move like a merchant’s hoping to sell survive.

Can you use it in a sentence? Swinging their pendulum

heads, they foretell how few survive.

Sour as berries died on the vine. My fingers stay

in the mouth of astonishment. Can such a shell survive?

Like the owl of Sunday morning cartoons, I want one big

chomp! To see what, on the tongue of a cracked bell, survives.

I reach time. I step in front of a honking car—jump

back. I outlive myself. Can’t help but survive.

A citizen of my catch-all drawer. A keep-sake of the stayed-

behind. A one-way ticket, that will to survive.

To worry is a law of nature. Is it enough? To be

inscribed in lighter hue: she is well-survived.

Veiled mother flickers bodily in the lamp-light

of you. Steps, unsteps in the melt that survives.

I want to love so well, that I spell a name with each

foot-fall in dirt. I reach palms down the wet well. Survive.

They say my mother’s was more than a death. Must mine be more

than a life? How to make my name undone? How to spell survive?

Poetry • Fall 2022

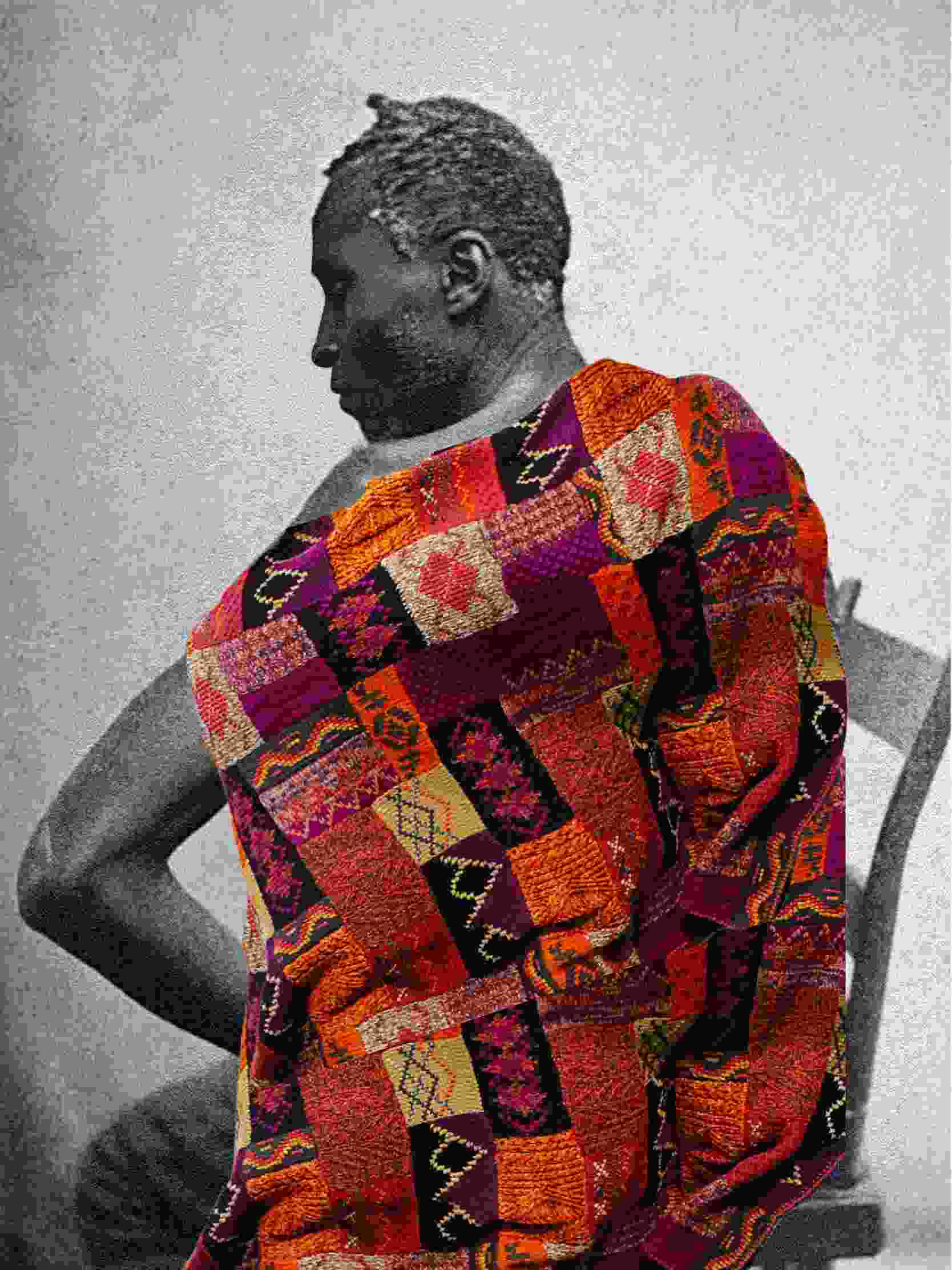

Father was a chair. I was tired but did not sit down. Father was a chair. I moved him to

the other room. When we watched TV, I could feel his chair-like energy growing more

and more anxious. Father was a chair. I went to school. Father was Father was a chair

pooling in the light. I could not tell if he wanted to be more than a chair. In the car, father

is a different kind of chair. Plush. Father drove me to a new school, stone, rich, white.

There was a woman I admired. There were many women. Beautiful warm sensual well-

dressed intellectual women. When they discovered I was not their daughter, they shook

their hair in shock. They had to move on. They were lively women who would never

survive in a pen. Father was a chair. I took a last look and closed the door.

Poetry • Fall 2022

Look. The deer is dead because I killed it.

Because I saw a hunk of flesh

and couldn’t remember

brakes existed. Because I was crying

and driving. Because it was winter

and things fall apart. Because

I kept going. Because I like to drive.

Because I know

these roads. Because the road

coming home is dark.

Because I go fast, faster when I’m sad.

Because I saw a pair of eyes

and closed mine.

Poetry • Fall 2022

and she picks me a tooth from her pile of tools, carved

in half-moon curves along its front edge. The other

edge covered in two-sided jags, falling, marked

by my inability to find it again. Behind her, columnar

light from the moon and a street lamp blazing. Cried

into her arms, she says, it’s alright to fall. Did you care

for bad teeth? I seized the morning on a fogged

up roof. I was stuck in Japan. Now it’s late September

and the dream house wakes me up. While I punch

at the clouds for air, for respite, and find pigeon dust,

she passes me the crumbs. It’s a fine bread crunched

into pieces. In any other city, you make a fuss

about the dream house, its engineers and bandits perched

on the deck with their rules, infinitudes, thin lust.

Fiction • Fall 2022

The day she turned forty, my mother burst into flames. I watched it reflected in my father’s glassy eyes across the dinner table, yellow and orange tongues of fire that danced in their devouring. Flesh doesn’t burn like wood or paper, doesn’t turn immediately to ash; it sears and bubbles, melts in layers, and sloughs away in chunks. She collected in a pile of chalky, mangled bone and blood broiled into sticky black tar.

Fiction • Fall 2022

If you’d like to experience love, book a plane ticket to western North Carolina and ask the tall woman at baggage claim what’s the best spot for trout fishing this time of year. She’ll tell you the second-best spot, but this is good enough; we’d all do well to safeguard our most precious places. Secure a riverside campsite and a few maps, even though you know these woods. Buy a tent and a sleeping bag and set them both up, and sleep sleep sleep, deeply. The next morning, throw your cell phone in the river. Or—place your cell phone in a large pot, then fill the pot with river water. Revive your neighbor’s dying fire and bring the pot to boil. Dispose according to cell-phone-disposal regulations. Get a fly rod and reel; buy the cheap but sturdy purple fly that the man behind the counter at the bait shop is at first hesitant to recommend. He’ll know you’re not to be toyed with. Set out to the tall woman’s second-best place, known only to eight people as Horseshoe Creek and otherwise unknown to everyone. It’ll be just over the edge of your paper map, on all four of its edges. When you get there, submit to interrogation—Dennis will want an account of how you found the place, who told you about this spot. Give him your whole life, in reverse. Don’t forget to mention that time when you were fourteen, when you snuck out of your house and biked to the next city over to steal some time with the boy you loved. Look straight ahead at the river when you say the part about how he’d gone home when you arrived. Don’t let your voice waver, and don’t blink, or so help Dennis God, he will hog-tie you and send you to the bottom of Lake Glenville. Believe him, but find joy in the knowledge that he’s been through much worse. Befriend Dennis, in every way you can. Give him every fish you catch. Baby him, but do not pander. He will call you names; he will step on your new boots and fling dust from the riverbed into your eyes. He will think up several jokes about your appearance, the way you talk, and he will say them all to you. They will hurt; they will be personal. Laugh, at all of them. Agree. He may put you in a chokehold, and if this happens to you, he intends to kill you. Make sure to use your Taser in this event, which you have brought and kept concealed and accessible in the waistband of your waders. He will, for a moment, relent. In a long silence, he will almost certainly say something about his runaway faggot son. Resist, resist. Just after last light, Dennis will leave abruptly. Follow him. Sprint, if you must. Ditch all your gear. You must time this next move extremely carefully: just as Dennis starts the engine of his red Ford F-150, hop into the truck’s bed. The coughing motor will cover up the sound. Once on the road, stay low. A vulture may follow the truck the whole way home; if she does, enjoy her presence. It will most likely contribute to the overall creepy vibe of the situation. Shoot her a thumbs-up. She’ll return it, most likely. The truck will stop at the end of a long gravel road. Jump out of the bed at the exact moment that the driver’s seat door shuts. This is of the utmost importance. When Dennis locks the truck, look toward the house. If I remember correctly it will be full of wicker and glass, sitting brightly at the foot of a giant hill. Look up at the crescent moon, like the bodies of two opposite lovers, light spooning dark. Consider this thought extremely profound, then forget it immediately. Pine after this lost memory until you die. Then wonder where the vulture went. Follow Dennis up the driveway and through the side door. Don’t worry, he won’t look behind him for the rest of the night. This is to your great advantage. Dennis will head to the kitchen and remove the paper-wrapped trout from a cooler. He will filet them beautifully, separating the meat from the shit-filled guts and humming a song from the year you were born. As he turns on the flame, the primer will click twice. Use these clicks to mask the two steps you will take to lunge toward the couch and slide under it. Wait, for an unconscionably long time. You will hear a knock on the door. It’ll be Eric, probably, or Alan—regardless, after a while they’ll all be there, the eight fishermen of Horseshoe Creek. They’ll turn on the television and—this next part is absolutely necessary to your survival —you must not, under any circumstances, scream, when your naked body flashes onto the screen. The men will be watching the video you shot and posted and monetized when you were with Ren, your ex from college who pretended he didn’t know you when you weren’t in bed together, and it’ll be the good one, when you surprised yourself with your own flexibility—Ren had asked you to put your legs behind your head, and you had scoffed, but he was serious, and when you tried it and actually did it it was like your body could do anything, and you remember the Yes and the Good job, Ren’s whispering, smiling mouth next to your ear, and you said Thank you and you meant it more than anyone ever had. I’ll give you a rare piece of information, because I like you: the eight men won’t be touching themselves, or each other. Eric will be on his cell phone and Alan will be transfixed, his hands dormant in his lap, looking twenty years younger. And Dennis will be on the couch, stroking the dog, with a blissful, pensive expression, as if fondly remembering something. When it’s over, watch the men clap each other on the back, goodbye. Watch Dennis give all the leftover trout to his friend whose kid is sick with pneumonia. Watch these men love each other in the age-old way, watch their love screaming in the distances between their bodies. Watch them neglect this love, their creation. Watch Dennis shut the front door. He will clean frantically; ten minutes later, the tall woman from baggage claim will arrive. They will lie on the couch together, and Family Feud will be on, but neither of them will be watching. They will be kissing gently, no tongue, each asking very little from the other, a simple something soft to save for later. Begin to love Dennis and the tall woman, and in loving these people, who so hate you, martyr yourself. Recalibrate your personal ethics; these river-rounded mountains were the very first philosophers. When you’re ready, crawl out from under the couch and present yourself to the two fallible lovers. Ask of them only their unconditional love, ask them about their first most favorite place. It is your birthright. It’s okay to feel sad when your tall mother shrieks; it’s okay to cry when Dennis, spewing paternity, goes to get the shotgun. Wipe these tears while you run down the front steps with the keys jingling in your hand. Realize you’re only crying because you think you’re supposed to. When you’ve put two state lines between you and the glass-and-wicker house, pull over at a rest stop. Touch your body, all over, to be sure it’s still there. Look at yourself in the bathroom mirror. Wash your hands. Put them in your mouth. Dry them, and wonder what to do next. Decide. Buy a Honey Bun from the nearest vending machine and eat it in the car and nearly keel over, it’s so good. Say thank you out loud, then freeze. Pick up the payphone. Call me.