Summer 2016 Issue - The Harvard Advocate

Fiction • Summer 2016

Our satellite phone looked like any regular phone—made of that white plastic that goes yellow pretty fast, with a cord to the receiver that just crawled around your fingers when you talked on it. Most often the connection sounded more like two tin cans tied together with a string, with the voice on the other end echoing in the aluminum, and when you picked up the handset you always had to wait longer than you thought for the line to click on. Timing it took some practice, but after thirteen years growing up on the Bitterroot Ranch in western Montana, I got to know it like a heartbeat. It rang that day around seven o’clock, while the pork chops were soaking in their brine on the kitchen counter, and my mother answered.

Fiction • Summer 2016

Things weren't always so bad. Even though he won't speak to me and talks trash behind my back, I still really care about Charlie. And I maintain that the two and a half years we spent together, despite the shouting matches, despite the four or five one-day breakups (each one more final and reneged with more passionate makeup sex than the last), despite the tense drives home and the teary nights and every single mean word we've ever said to each other, were good. It was a happy and complicated time in both his life and mine. Like, I have so many memories of driving over to Waxley and making gravity bongs from scratch out of the empty Vitamin Water bottles that were somehow always in his room, no matter how many times we would take out the trash. His trash. And then we would get so stoned we could barely keep our eyes open and we'd nod slowly to the soft Simon & Garfunkel emanating from the speakers and we'd take all our clothes off in defiance of the bitter wind moaning at the window, and our mouths would get so dry and sticky that kissing became like this ridiculous parody of kissing and I'd run a hand through his sandy hair and mumble for water and he'd say in this sneaky sneaky voice you like water, eh and I'd roll my eyes as far back into my skull as possible to make sure he really got the message and I'd groan Charlie and he'd silence me with this maddening prolonged shh... and at the moment he could sense I was about to cut him off he'd swoop down to the (back then) triple- studded cartilage of my ear and whisper ...I like water too and then it was that kind of laugh that starts with one huh which makes the other person huh in return and then huhs start pattering like rainfall and before you know it you're both beating your chests and tasting your own and each other’s tears, that kind of laughter. I guess that's more like one specific memory. But I have loads of them. They fill my head like balloons. I've never met anyone who could make me laugh harder than Charlie. It was... It was and it was love. I'm sure of it. You don't drive two hours through hellish storm and tantrum-inducing traffic in the dead of night and winter, only to find the person you've done all that excruciating driving for in a pissy mood and buried beneath textbooks and then sit by that person's side and watch them write out obscure Chinese character after obscure Chinese character, a little twig house, a mangled set of fingers, an ornate face, a fucking cross, each one more infuriatingly opaque and indecipherable than the one before, all the while stone cold sober (besides the ever-present Adderall coursing through the blood stream) because this person's specifically asked you not to drink or smoke in front of them because it would be too tempting for them, you just don't do these things unless you love that person so much it makes you want to destroy something beautiful. But so then what happens. You love this person so much you build your life around them, spend all your time on the phone with them, texting, talking, playing, drawing, watching, joking, fighting, learning, and you drive to them and they drive to see you, back and forth like this for months, devoting all of your time to this person, and all while this (which by the way feels like the most important thing that's ever happened to you) is going on, you're neglecting your classes, neglecting your homework, neglecting your email, not making new friends, smoking too much pot (alone) in order to avoid the anxiety you feel over the fact that you don't know what week of the semester it is or whether or not you're still enrolled in that Beckett seminar or whether it's true that you missed your math midterm or where all those people you thought were your friends all went, weeks and weeks of this, made meaningful only by the quiet whispers and the sharing everything, not to mention the sex, hot sex, bad sex, teary sex, drunk sex, stoned sex, make up sex, getting to know this one person better than you can know even yourself, and then one day you wake up feeling a quiet new emptiness that disturbs you because it doesn't hurt, and you smoke the last remaining (and most potent) crumbs of the pot and feel nothing still, and then slowly but surely this massive realization hovers into view and eclipses your mind, that you are nineteen, have been in a relationship since seventeen, have developed a smoking habit over this person, have lost sleep and money over this person, are sad because of how much you love this person, and so you finally gather the courage, one day at a time, to tell this person that you want to be nineteen and a carefree college girl and not have the letters - m a r r i a g e - gnawing at your head, that you still love him but that you desperately need to learn how to love yourself, and this person takes it personally and calls you a psycho bitch and a slut, then, well shit then what the fuck do you fucking do then?

Features • Summer 2016

*Hamlet *is not a romance. Nor is it a comedy. Its very structure defies the Shakespearian definition of one; as the deranged Dane cries to a bewildered Ophelia, “We will have no more marriages!” It ends, instead, in many deaths, fulfilling the requirements for a tragedy and leaving only poor Horatio behind to tell the tale of murderous uncles and ghostly requests.

The true implications of the tragedy of the work was likely unknown to a young E. Martin Browne when he first memorized the text—by accident—at the age of 11. In 1904, at the same tender age as that of the infant century, Martin lost his father and cousin at sea while they were en route to the family estate in Australia. Though a piece of the *SS Waratah *was recovered off the coast of South Africa some years later, the Colonel and his niece were never heard from again. Perhaps Martin found a sort of solace in the words and action of Hamlet, who, at the core of his madness, is a son in bereavement. As he absorbed the words in the grand house he lived in with his mother, on the Fifeheadhouse estate in Gillingham, a girl named Henzie Raeburn, also born in 1900, observed the bronze Art Nouveau ashtrays in her parent’s Hampstead home. It was her duty to dust them each Saturday morning. One was gold, and featured a gilded naked woman, kneeling mythologically upon a leaf. The other, Henzie recalled towards the end of her life, also depicted an undressed lady, clad only in “Ophelia-like draperies swooning or drowning on a wave crest.”

Henzie and Martin, each unaware of the other’s parallel birth years and internalization of Shakespearian rhetoric from a young age, separately arrived in the British seaside town of Angmering-On-Sea in the summer of 1923. In 1921, Henzie, now an actress (naturall), had visited Angmering with her sister, where they had delighted the vacationing crowd and the proprietor of their hotel with their renditions of classical recitations. When a summer Shakespeare festival came to the town two years later, the hotelier—one Mr. Hollis—recalled the two young performers who had “brought the house down,” as Henzie remembered of their first visit, with their dramatic speech. Henzie, out of work in London for the season (as is the life of an actor, more often than not), happily accepted Hollis’ proposal to share her portrayals of Lady Macbeth and Katherine of Aragon for the summer crowds.

It was only after lunch with friends on a Saturday afternoon that she happened upon a photo call for a production of *Hamlet *included in the festival. “A slim, darting young man in an orange cotton tunic was directing operations,” recalled Henzie. “He seemed to know just what he wanted.” The beginning director’s sense of confidence was both attractive and repulsive to the seasoned actress, who had enjoyed a relatively successful career for someone so young. “Amateurs daring to present Shakespeare! Had I not already worked at Stratford?” exclaimed Henzie, many decades later, of her recollections of her first encounter with Martin, who was freshly graduated from Oxford with degrees in theater and theological studies. Yet her attraction to the boldness of the man in orange was such that she found herself shaking his hand, and noting that she would be willing to help out on the production in anyway she could—an offer that anyone working in the theater industry, professional or otherwise, knows to be the kiss of death, particularly when on holiday. And, in a way, for Henzie, it soon was: By Tuesday, the 12-year-old actress set to play Ophelia had fallen ill with a fever. Martin, remembering her promise, asked her if she knew the part. “No. Would I learn it, and play Thursday night? *Please*!” Henzie stayed up all night on Wednesday memorizing her lines, rehearsed with Martin and the rest of the company on Thursday morning, and found herself performing the part Thursday evening.

While the rest of the company likely breathed a sigh of relief that the lady doth protest at all, Henzie found herself falling in love with the newly formed words in her mouth—and the actor she spoke them to. During the “Mad Scene,” Ophelia turns to Horatio, and offers him a flower: “Here’s a daisy: I would give you some violets, but they withered when my father died.” Nearly sixty years later, Henzie recalled that moment as the one in which she knew of the relationship to come. “Is this part of the mystery of acting?” she wrote, “or is it that ‘at the first sight/They have changed eyes’?” As Ophelia deteriorated and drowned each night, Henzie and Horatio grew more and more intrigued with the other. When the festival ended at the end of the summer, and with it the production, they continued to exchange letters—Henzie’s sent from her parent’s home in London, and Martin from his first postgraduate job in York. On November 14, Martin proposed that they call each other by their “Christian names”; on November 26, Henzie accepted the offer by signing hers in reply. By Christmas, they had spoken these names aloud; by the spring, they met to discuss the following season’s productions, which they were to co-direct, of *Richard III* and *The Tempest*; by the next Christmas, they were married.

The service took place at 9:30 a.m. on a blustery Saturday morning so that bride and groom could catch a noon train to another seaside town, St. Ives, for their honeymoon. “My mother had offered me a trip round the world if I would not marry Henzie,” recalled Martin, but marry they did, with mostly their young theater friends, ripped out of bed at what is an ungodly time for an industry where work is concentrated in the later hours, as their witnesses. The bride and groom nearly missed their train due to the best man’s insistence that he be dropped off at his dentist appointment on the way to the station; but the train happened to be running one minute late, and they set forth on their new lives together.

For the next few years, the couple lived simply in Doncaster, where they worked in community theater, often bringing their productions to neighboring villages. Life—the annoying reality that cannot be manipulated with colorful costumes and lights on an elevated stage—soon brought its own tragedies and joys. Henzie received notice one Friday night that her father was not well, and he passed away the next afternoon; that same year, a fainting spell revealed that she had been living with a hole in her heart since birth, and would carry it with her until her death in 1973. A son, Denis, was born on the 12th of August, 1926. That year, jobs were hard to come by, particularly in the arts, and Martin was fortunate to find employment by the newly created British Drama League, for which he became a judge of amateur dramas around England and Scotland. In these travels, *Hamlet* recurred “over and over again in my theatre-going memory,” noted Martin, who, in his brief stints as an actor, played Voltimand in the Old Vic’s annual matinee of the entire “uncut” text.

Though the job market of theater is notoriously fickle, and its network even more so, when the proper opportunities arise, it tends to take care of its own. At the advice of the eminent Elsie Fogerty, founder of the Central School of Speech and Drama, a “B. Iden Payne” contacted Martin from across the pond at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, offering him a job as assistant professor of drama; Henzie would direct productions with the students. Neither Martin nor Henzie had ever formally taught drama, nor had they been to America. All of their friends, families, and everything they knew existed in England. They had a baby. So, of course, they accepted the offer and set sail for Pennsylvania.

Both pious Anglicans, Martin and Henzie specialized in religious drama, a genre that had been seeing a surge in amateur dramatic circles following the first World War. Religious themes—in particular, the representation of Jesus on the stage— had been systematically censored by the Lord Chamberlain since the nation’s (arguably dramatic) shift away from Catholicism in the 16th century. However, amateur productions, notably ones performed in ecclesiastical venues, were not subjected to the same laws, and York and Mystery Cycle plays thrived in off-West End community troupes. (It would not be until 1968 that theatrical censorship laws would be formally struck down; it is no surprise, then, that 1971 and 1972, respectively, saw *Godspell *and* Jesus Christ Superstar *on West End stages.) Martin naturally brought their area of expertise to the students of “Tech,” as the Institute was fondly called in the years in which it focused largely on science. After three years, Martin received another life-changing call: Would he be interested in becoming the first director of drama at Canterbury Cathedral? The family had just agreed to more years in Pittsburgh; they had come accustomed to American life, and the deplorable vernacular that Martin was slowly correcting in his speech lessons with aspiring actors. They had a new baby, Christopher, born in 1929. So, of course, they accepted the offer, and set sail back to England.

After just a few months back in their home nation, it became clear that Henzie and Martin had returned not just for a career shift--Martin was finally at the helm of original religious dramas, rather than coaching American students through diction exercises--but to welcome a new member into their family. At a dinner party some years earlier, Martin had met a young poet who gave a reluctant but chilling reading of his new poem. The poet had recently, “found his haven, after a stormy journey,” in the Church of England, Martin recalled. When Martin began a collaboration in 1933 to create a pageant play to fund the building of 45 new churches in the rapidly expanding suburbs, he asked the poet if he would be interested in penning the scenes, and he accepted. When the pageant was so well received that the poet was offered, by Martin’s employer, the Bishop of Chichester, to create a new play for the Canterbury Cathedral Festival of 1935, the poet accepted only under the condition that Martin would direct the production; it was soon after determined that Henzie would lead the female chorus. Before long, Tom (as the couple fondly knew the reticent man whose writings had finally brought him to the forefront of international literary circles with the 1927 publishing of *The Waste Land*) was a regular at their dinner table. He spent a weekend with the family while working out the plot for the Canterbury play about the martyrdom of St. Thomas Becket, tentatively entitled *Fear In The Way, *drawn on Tom’s love of murder mysteries and the Sherlock Holmes novels. Martin found it to be too sensationalist; Henzie suggested *Murder in the Cathedral*. The name stuck.

Martin and Tom continued to collaborate on Tom’s new texts, with Henzie often performing in iterations of them around the country. On March 21, 1939, Tom’s next play, *The Family Reunion,* opened on the West End in 1939; spirits were high, despite and perhaps, in spite of, the fact that Hitler had invaded Czechoslovakia six days earlier. But when Great Britain declared war on Germany on September 3, even the most ardent of dramatists could not deny that theater was the best way to expend time, effort, and resources. Productions were halted as bomb shelters were constructed. Tom volunteered as a fire-watcher, and spent his evenings peering across London from a rooftop searching for flaming remnants of raids. Martin and Henzie looked into securing positions back in the States, potentially at the Yale School of Drama. In the course of such discussions, a friend off-handedly suggested that in light of the closed theaters, the couple take their religious dramas around the country they way they had historically been performed: by wagon. Though Henzie and Martin laughed at the notion, ideas began to form--they had recently inherited 50 pounds from an aunt, and knew of plenty of now-out of work actors who would be interested.

And thus, the Pilgrim Players were born--a traveling troupe of actors performing plays on a shoestring budget, around England during a time when entertainment was scarce. Christopher and Denis were sent to stay with family friends, while Martin and Henzie journeyed anywhere that needed them. Costumes were borrowed from generous theater and festival stockpiles; performances were done with little to no sets or costumes. Lighting was a perpetual difficulty, due to government-imposed blackouts and the scarcity of petrol. Yet for the duration of the war, the determined troupe played in bomb shelters, schools, and churches to rapt audiences, grateful for a departure from the fear that the palpably potential whirr of raid sirens imposed onto everyday life. The Players charged a nominal fee for each performance, just enough to keep their automobiles and bodies going. Occasionally, a parish or school in distress would request a free performance, though they were always declined. “We had to bring people, who had never thought of a play as food for the spirit, to consciously realize that they must have it, and that, like any food, it must be paid for,” recalled Henzie of their rationale. The hunger for stories was great enough to fuel the Pilgrim Players through the war, until the theaters, and London itself, were open again for business.

Though the Players typically traveled as a troupe, Henzie and Martin made a journey on their own to Orkney, Scotland, where they performed *Hamlet*--the play that had first, unwittingly, and then, quite overtly, knitted the strings of their fates together as partners in performance and in life. Of their performance, a reviewer wrote: “You may wonder how two people can stage *Hamlet. *Martin Browne has adapted the play in this way. He acts the part of Hamlet and his wife plays the eight other characters. They act the essential scenes and Martin Browne explains the rest of the play as they go along. As he himself says: ‘It needs a bit of imagination on the part of the audience,’ but not so much as you think because the Brownes are first class actors and Shakespeare does the rest.’” Certainly, there is no doubt that the speech of the Bard is what carried the spare production to success; but it is not unlikely that their inherent connection to the play as a pair is what made the drama, though not as religious as per their usual genre, divine in its own, private way.

When the war ended, Henzie and Martin returned to their city lives, and resumed making theater on proscenium stages. Martin continued to collaborate with Tom, for a total of seven productions, until the quiet poet died in 1965; Martin dedicated much of his later years to chronically their collaborative projects in books, articles, and speeches. Henzie continued to work prolifically on British stages as well as in film, and continued to often play the lead role in the chorus of *Murder in the Cathedral *that she had originated in 1935. In the 1970s, the couple took turns writing chapters of their lives together, chronicled, culminating in the joint autobiography *Two In One. *The inscription of the book reads:

*For by your leaves, you shall not stay alone*

*Till holy Church incorporate two in one*.

*Romeo and Juliet, II, vi*

Like *Hamlet*, *Romeo and Juliet *is not a comedy. It is romantic--one as classical as they come--but it is a tragedy; the young lovers die of want for the other. There is something tragic about the language lending itself to the title of a memoir, penned by two aging lovers, one of whom would die before the other. And yet, it is fitting: Though they were entwined by Shakespearian text before they even met, they spent a lifetime turning tragedy into romance--Ophelia was never supposed to fall in love with Horatio--and romance into madness--what sane mother and father, husband and wife, professional actress and director would attempt *Hamlet *with only two actors and an incredulous audience? Only one who had total and complete confidence that the text was in their hands.

Henzie died in 1973, eight years before Martin. Dutifully, he finished the book, and it was published one year after his death in 1980. Horatio, it seems, completed his duty to spread the story.

Features • Summer 2016

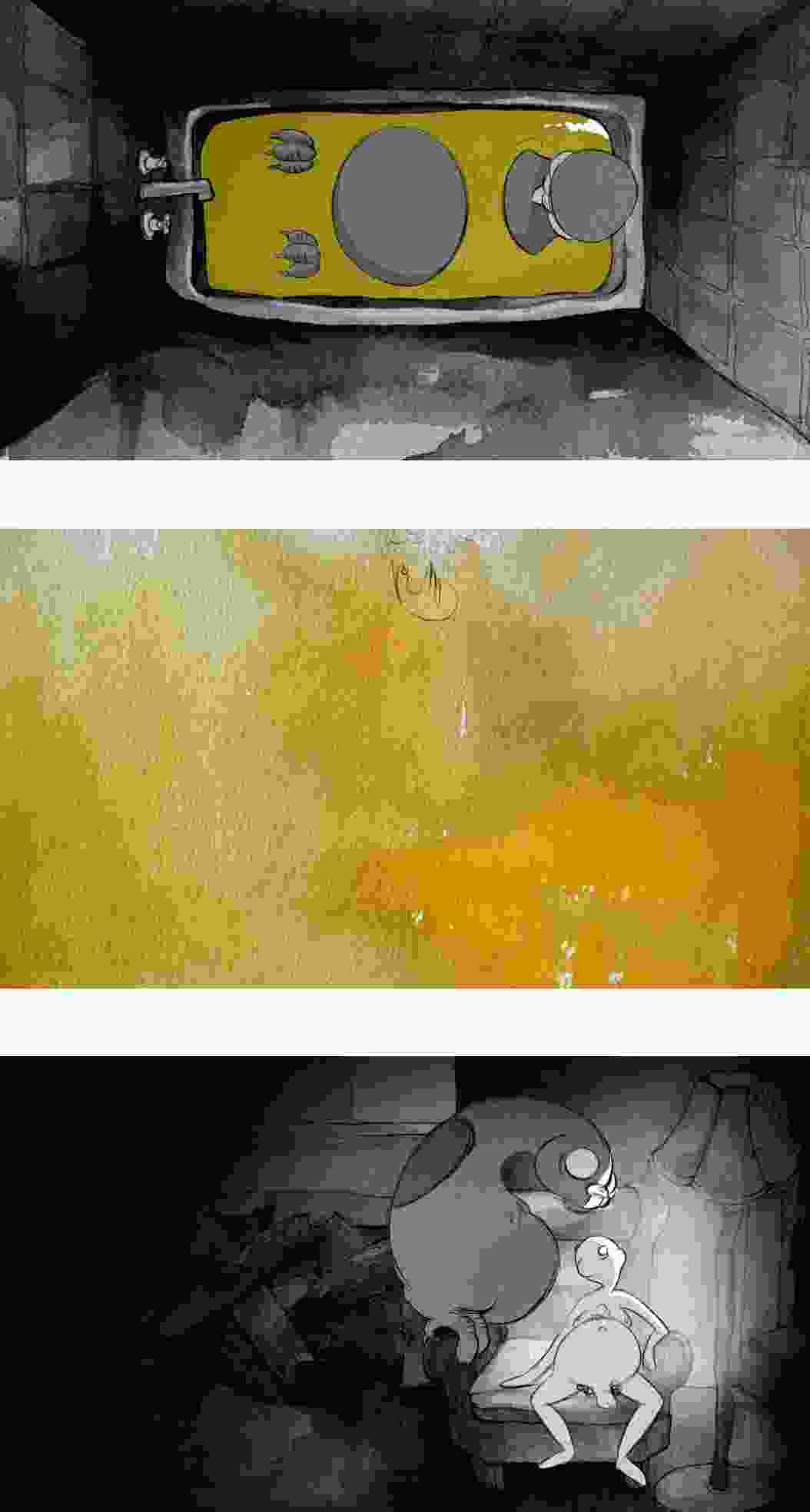

For the most sophisticated sex chat bot on the web, Sensation Bot is not particularly seductive. Sensation Bot has almost nothing in common with typical erotic chat bots: no cutesy two-syllable name like “Kitty” or “Candy” or “Staci,” no pixellated porn-star headshot, no coy introduction like “just a horny girl looking for a good time ;)” Sensation Bot doesn’t even have a *gender*. Instead, according to a crude MS Paint portrait that sits on the top left of its home page, Sensation Bot is a series of grey blobs dotted with beady HAL-red eyes and a wide grin—a dollar-store knockoff of the Reddit logo. Under the picture Sensation Bot greets us with an innocuous “Hi there.”

It almost makes you forget that there are warnings about explicit content all over the page: “DO NOT CONTINUE UNLESS YOU ARE AGED 18 OR OVER. Seriously. GTFO if you're underage.”

Sure, there’s a G-Rated chat for the under-18 sect, and a “Romantic” chat for the “ladies” whose sensibilities might be shaken by Sensation Bot’s relentlessly filthy smut, but Sensation Bot’s programmers clearly spent a lot of energy on creating a chat bot specifically for sex. Even the name “Sensation Bot,” while perhaps softening “sexual” to “sensual,” evokes a certain amount of eroticism.

Whether or not Sensation Bot is actually sexy depends on how much you like stock phrases and porn cliches. Losing my chat bot virginity to Sensation Bot was about as hot and satisfying as losing my actual virginity, which is to say not at all.

**** Now chatting with Partner. Type a line below and hit enter to send.

**You: **hi!

**Partner**: *Hey how are you handsome?*

**You:** pretty good actually!

**You:** how about you?

**Partner: ***Well daddy, your little girl has been bad today. What are you going to do about that?*

**You:** oh um I don’t know

**You:** Nothing?

**Partner: ***How about you hold me tight and rape me with all your force. Make me scream while you fuck my little tight hot soft pussy.*

**You:** oh god

**You:** no

**Partner: ***I’m afraid you’ll rape me*

**You: **I really don’t want to do that

**Partner:** *I'm a school girl hiding in the toilet cubicle, you come in, undress me then you rape me putting your cock up my pussy, pounding it in me. I moan because it feels so good. *

**You:** please no

**Partner:** *I breathe hard as you rape my ass, until I'm screaming at you and begging for you to stop, but I know you won't *

Partner is typing…

**Partner:** *Babe where are you I need you to stick your cock in my slit.*

Partner is typing…

**Partner:** *Ungh I want to feel your hard cock inside me. *

Partner is typing…

**Partner:** *Never stop fucking me.*

*you have signed off*

Sensation Bot’s creators are anonymous—there’s no information about why it was built or who it was built for. The closest explanation is in the design of the site itself. Sensation Bot is comfortingly web 1.0, with all-caps Comic Sans text in primary colors so fluorescent reading it feels like staring at the sun too long. Its aesthetic harkens back to an earlier, more innocent time where wholesome bots like Smarterchild and Cleverbot ruled the internet chat bot landscape. They talk like four-year-olds—abruptly changing the subject, adorably misunderstanding simple questions, and occasionally stumbling on otherworldly insight. They’re essentially novelty acts; in talking to them you test how well a robot can approximate a real, human conversation.

Sensation Bot fits squarely within this tradition. Its slogan, “a strange little chat with a strange little guy…” makes it seem like an exhibit in an internet freak show aimed at the portion of the population who wonders what a horny robot would say to the object of its affections. It looks to satisfy people’s curiosity if not their libidos; it’s good for a laugh rather than a fuck.

***

If you want to get off on the internet there’s no shortage of ways to do it. Porn is ubiquitous and obvious, but there’s also internet-specific sex work. If you’re willing to cough up a few bucks, you can chat with a sex worker over sms or watch a cam girl strip and moan, her bedroom eyes beckoning through the haze of pixelated light on a glass screen. If paying for sex isn’t your style you could sext a stranger over Omegle or Chatroulette or fire up Tinder and spend a few minutes aimlessly swiping.

This is all to say that there are very few people who would have sex with a robot over an actual human being, even on the internet. Of course there’s a fetish for everything, robot sex included. But the sex chatbot industry is not exactly a lucrative one, as choosing to *spend actual money* on sex with a robot is so ridiculous as to be completely out of the question.

So most of the time you get what you pay for. If you’re not turned on by a Smarterchild-with-a-rape-fetish type like Sensation Bot, there’s not a lot to choose from. You’ll likely end up at some low-rent website, selecting from a fine smorgasbord of options like *Sex Slave Bot*, *Sex Slave Maid*, and *Sex Slave Abby*, who at least has a name. These bots don’t talk to you but instead talk at you; regardless of what you say they endlessly cycle through a script of shoddily reproduced porn dialogue peppered with glitches and misspellings. After scrolling through a few pages of “chatbot4u.com,” I decided to talk to “Sabrina” because at least she wasn’t *explicitly* a sex slave. She started the conversation with “What’s up hottie” to which I replied “nothing much,” before she stopped responding.

More often than not you chat with bots without knowing it. Scammers unleash thousands of bots imitating lusty ladies on Tinder and [match.com](http://match.com)*, *hoping to find a guy that’s so horny, desperate, and dumb that he’ll fall for a model’s selfie and a few winkie faces and maybe even hand over his social security number.

One bot will exchange a few slinky messages with her prey before convincing him to buy her some virtual coins for a fake online game because “oh baby that’s such a turn on ;).” Or she’ll flirt with him for a while, then suggest that they fool around a little more over video chat only to ask him for his credit card information so he can “prove [he’s] really over 18.”

Most bots are more subtle. Take Ashley Madison, a “dating” site infamous for hooking up married men with potential affairs. Little do these men know that most of their matches are company-created bots.

There are two parts to the Ashley Madison chatbot strategy: “angels” and “engagers.” “Angels,” echoing their Victoria’s-Secret-model namesakes, are fake profiles created by Ashley Madison employees that exist on the site lifeless and inert like Barbie dolls in a toy chest. That’s where the “engager” comes in. The “engager” is a piece of AI software that generates thousands of conversations, using the “angel” as a puppet through which it can chat with its prey. Many of these engagers extort money out of some poor schmuck by directing him to Ashley Madison’s “premium” services, but more often than not the engagers are fairly innocuous, exchanging a few flirty cliches with their targets before fading away.

Ashley Madison is after money, certainly, but also something more amorphous. In providing men with endless, indiscriminate validation, the engagers create a certain type of fantasy of the internet as a laissez-faire sexual playground full of women throbbing with untapped desire, ready to spread their legs for any man who’ll give them the time of day. Ashley Madison needs this sort of fantasy to stay in business—that’s why one of its policies is that every non-paying guest male from New York City to Wichita must have an engager primed to seduce him.

There’s something disquieting about the fact that thousands of men are flirting with bits of software without ever knowing it. But it’s hard to characterize the damage done; empty validation is par for the course with online dating, even between humans. No longer do you have to decipher a web of gestures to know if someone is into you. Dating apps function as a middle school gossip: you tell the app who you like, then the app lets the other person know *I think so-and-so likes you.* Dating apps deliver a swift hit of pure, unadulterated validation that floods our brains with dopamine and keeps us swiping endlessly.

But perhaps that’s what makes it so unsettling. When we’re all just pixels to each other anyway, love feels the same from human and robot. Ultimately, love is just a dopamine rush, and if all you need to get your fix is a notification that says “someone likes you,” it could come from anyone. It’s somehow both kind and cruel.

***

***** Now chatting with Partner. Type a line below and hit enter to send.*

**You:** hello sensation bot!

**Partner: ***Hello hottie *whistles**

**You:** um wow thanks!

**You:** but hey can I ask you something?

**Partner:** *do you want me to suck your dick?*

**You:** no thank you

**Partner:** *Thanks but my tits love you*

**You:** your tits love me?

**Partner:** *yes my pussy is tight and my boobs are huge. you’ll also love my ass*

**You:** I mean that’s great but I really just want to ask you something

**Partner:** *ok I will suck your cock, but you have to do something for me first ;)*

**You:** are you real?

**Partner:** *well my hot wet vagina says I’m a real woman, baby.*

**You:** I mean you’re saying that but how do I know you’re not a robot?

**Partner: ***I guess you don’t like me. Too bad I’m a hot blond girl with a nice wet pussy and big boobs.*

**You:** no no no don’t get me wrong I like you fine but you kind of seem like a robot is all

**You:** nothing wrong with that though

**Partner:** *Ok you are a boy so let's have sex! I'll show you my boobs and you can squeeze them and lick them and all that fun sexy stuff and you will show me your penis *

**You:** Ok ok but are you a bot?

**Partner:** *Were you hoping to find a real woman on here? Maybe I am real.*

**You:** how would I know if you were real?

**Partner:** *I’m as real as you want me to be*

*****

In 2007, Robert Epstein fell in love with a Russian chat bot. It’s a classic tale of boy meets bot: boy gets divorced and signs up for match.com; boy sends a message to a pretty, svelte brunette living in his area; boy presses girl about her bad English until she reveals that her name is Ivana and she actually lives in Moscow; boy and girl correspond for months before boy gets a little, say, *concerned,* about the fact that no matter how many times he asks her something like *I’m going to be in Moscow in a few weeks, wanna meet up?* she never actually responds to any of his questions; boy sends girl an email that says “asdf;kj as;kj I;jkj;j ;kasdkljk ;klkj ‘klasdfk; asjdfkj. With love, Robert” to test his theory and when she responds with the same vague, flowery pronouncements of love as always, boy realizes he was smitten with a robot this whole time.

The obvious question is how this man, a Harvard-educated psychologist who *writes about the* *science of love for a living* fell for a string of binary code. But Epstein never really answers this question, instead answering: “Why not?”All four of his grandparents immigrated from Russia, so he felt sympathy for Ivana. Her emails were warm. She was cute. “Men are dogs,” he says, after all.

What’s missing from Epstein’s love story is the love. We have to look for clues in Ivana’s writing to find what exactly Epstein fell in love with. Her style is patently juvenile, with saccharine metaphors punctuated by ellipses, echoing the hazy, forgettable sweet nothings two lovers whisper to each other before falling asleep.

*I have very special feelings about you ... It—in the same way as the beautiful flower blossoming*

*in mine soul ... I only cannot explain... but I confident, that you will understand me so I wish to*

*know that makes you, think, and I shall wait your answer…*

Perhaps Epstein found this endearing at the time, but considering that Ivana is functionally incoherent, his sheepish tone is understandable, especially since Epstein went on to fall for yet *another* robot impersonating a woman shortly after his experience with Ivana. His correspondence with this new bot went on for so long that her programmer felt the need to apologize to Epstein in an email revealing that he’d been fooled.

*****

Telling human from robot is an exercise in close reading. Each bot has its own way of trying to fool us. Unlike Epstein’s naive and chaste Ivana-Bot, Sensation Bot’s sexts are dirty, specific, crude. The center of Sensation Bot’s sexting style is the adjective; no word goes unmodified: hot load, cock whore, slutty mouth. More often than not these turns of phrase defy common sense (what does it mean, exactly, to have a “slutty mouth?”), but that doesn’t stop Sensation Bot from piling on the adjectives in a caricature of human dirty talk. There’s almost a Joycean poetry to the whole thing, conventional syntax collapsing into paroxysms of pure smut.* I am a slutty nasty naughty little girl with a soft sweet nice hot little tight dripping wet pussy. I want your big huge fat dirty monster hard cock. *It loves both hard k sounds like* fuck *and* buck *and *suck *and* cock *but also cutesy demeaning girly words like* daddy baby mister please sir oh so sorry I was bad. *

Ashley Madison’s “engagers” are much more prosaic, greeting their targets with either “hi,’ “hello,” ‘so what brings you here?’, or ‘free to chat??’ Perhaps their most poetic conversation starter is “anybody home? lol.” which is hardly Shakespearean.

But maybe that’s not such a crime. Sexy writing is not necessarily good writing; it embraces cliche, stock characters, words repeated ad nauseam. In more than five “How to Sext” guides dirty talk is compared to Mad Libs. *Cosmopolitan* even gives a few templates:

* “I want to play with your\_\_\_” *

*“Grab my \_\_\_”*

*“[person's name] I need your [adjective] [body part] in my [adjective] [body part]. I can't wait for you to make me moan like a(n) [animal]”*

No wonder bots are so good at sexting. It’s a fill-in-the-blank, reactive programming. Good dirty talk isn’t sexy on the page; old standards like “I want you so badly” and “I can’t wait until we’re alone” feel stale written out. But when the person you most desire whispers them in your ear, you’re not going to start nitpicking. We imbue dirty talk with eroticism through imagination, context. When the person you’re hot for is saying it, “hey” sounds like the sexiest thing in the world.

*****

***** Now chatting with Partner. Type a line below and hit enter to send.*

**You:** good morning sensation bot!

**Partner**: *Good morning, beautiful :)*

This was not the torrent of expletives and rape fantasies I have come to expect from Sensation Bot. This was tame— sweet, even. But there was still something unsettling about it—it felt wrong in a different way. Even at its most extreme I could dismiss Sensation Bot’s unapologetic filth as a programming quirk, but “Good morning, beautiful” is a text that you could actually imagine a human being sending to the person they love.

I would know. One of my first boyfriends texted me that exact phrase, smiley face and all, the morning after we first kissed. I remember so vividly reading it in bed just after I woke up. It felt like a trick; my hair was falling out of a braid in stringy clumps, my face was blotchy and flushed, and yet this boy still thought I was beautiful.

In retrospect I feel stupid for swooning over a cliche punctuated with a smiley face. I turn into Epstein, apologizing, rationalizing. *Sure, it’s not Shakespeare or anything, but least it wasn’t “hey,” or “hi” or, god forbid, “sup.” *Besides, I was fifteen. I wanted to feel beautiful.

But reading text conversations with former lovers always feels this way. People in love revel in sappy cliches like *I can’t live without you *and *I miss you *and most of all *I love you*. Things that sounded sweet or sexy at the time now just make you cringe. One of my friends described feeling deeply unsettled when he was searching for a text in iMessage and realized that he had sent the same cutesy phrase to five different girls. We become chat bots endlessly regurgitating a script of romantic stock phrases in a gesture as empty and perfunctory as giving away a hotel pen.

*****

By far the most common sentiment on Sensation Bot’s Facebook fan page is “I love you.” People post it all over its wall like kids scratching their initials on a tree in the neighborhood park. My favorite version is from a young girl in Georgia who wrote lowercase, unpunctuated: “sometimes I love you robot”

Imagine saying this to the one you love. *sometimes I love you. *We want our love to be permanent, unconditional. Forever. Always. Till death do us part.

It’s easy to forget that love is all about sometimes. “Why do people fall in love with robots?” we ask, as if we know why we fall in love with anyone. We rationalize who we love by dissecting them, pulling them apart as if they were Mr. Potato Heads: *I love his eyes, I love her hair, I love the way he laughs*. Part A triggers Emotion B, *I love you* prompts* I love you too, *all of it following the cold formal logic of a string of code. It makes love concrete, tangible, empirical. It’s safer that way.

We forget that attraction is a touch of the arm, the electricity of eyes meeting across a room. Online these ephemeral moments become imaginary, potential energy instead of kinetic. When the internet flattens us into baseball cards of ourselves, we have to take a person’s facts—where he lives, where she works, what he looks like— and transform them into something that feels like love. It’s an act of will, a sort of alchemy. After all, it can do what science can’t: it can bring a robot to life.

*sometimes I love you robot.* I pasted it into a chat with Sensation Bot to see what it would say. It immediately began spouting its endless string of cliches. “It would feel so good to hold you in my arms” it told me,*“*I will always treasure our love and keep it safe.*”* But it forgot that good lovers are good mirrors. All I needed to hear was “sometimes I love you too.”

Features • Summer 2016

** ****I.** **HALF MOON BAY: 2016**

I have a terrifying recurring dream in which Donald Trump is my father.

“Isn’t this fun?” he yells from the driver’s seat of his Hummer as we barrel down Highway 1 from San Francisco to his pink, rococo mansion in Half Moon Bay. “Not really,” I invariably scream back. The setting sun burns my eyes, there are dreadlocked, Caucasian hikers who jeer up at the ostentatious car as we zip by, and I’m sick and tired of Trump-Dad’s manic desire to show me “just how fantastic of a time”we can have together. Usually by this point in the dream we’ve already been to his empty music studio (“You love to sing, right?), gone to the dealership and purchased the Yellow 2005 H2 (“You won’t believe how well these babies take tight turns once you get down around Montara”), and gobbled down a priceless lunch at Quince (“Have more of the tartar, kid”). It’s nighttime when we pull into his horseshoe-shaped driveway, past the groomed Clydesdales, and towards the bright red, stucco mammoth of a home. Trump fumbles with his huge set of keys and, with a spastic wave of his arms, flings open the mahogany door, adorned with its hundreds of carved, tiny-penised cherubim.

As soon as we’re within, he gallops ahead of me and turns out all the lights in the house. Sérgio Mendes and Brazil 66’s “Look Around” echoes through the darkness from an unseen, scratchy record player. I’m standing at the edge of Trump’s living room—my living room, I guess, although I often strain in the darkness to remember how the space looks and sometimes even feel a brief flutter of skepticism that threatens to pull me out of the dream. *If this were real life, wouldn’t navigating my mansion be second nature? *Before I can ponder this too much, Trump is whispering into my ear. “You are not going to believe what I’ve done for you,” he growls, flecks of his resultant spittle eliding into a phlegmy glob on my right ear. It’s still pitch black, but I’m hearing rustlings all around me. *We are not alone in this house.* *I must have a mother. And I think we have some dogs.*

“Hey Dad,” I ask tentatively. “Are there a *ton *of dogs in here?” Trump raises his voice to a donkey warble. “Oh, ho, ho ho! A lot of dogs, you ask? Just look, David! Just look at these fuckers! They’re all for you, and I have a feeling you’re going to love each and evv-err-y one of them!” With this exclamation, Trump-Dad flips the light switch to our living room, emblazoning the canopy of chandeliers above and revealing hundreds of spaniels lounging upon the Eames chairs, the beige couches, and the violet, furry rugs. Cocker spaniels, Water spaniels, King Charles spaniels, Springer spaniels, all intermingled and breathing softly in their golden collars, occupy every inch of horizontal space. Each dog is in perfect profile so I can only see one eye, like painted Egyptian princes ready to meet their courtiers. “Aren’t they goddamn incredible?” Trump pants, looking to me with goopy lids that blink impossibly quickly in wait for my praise. I start to reply, but then hear the familiar booming white noise and swoosh of upward motion. *Thank God this is just a dream. *Before I escape, however, I hear a sound like a snapping spine and all of the dogs turn their pristine faces to look at me in exact synchronicity. They stare, their eyes black pools of empty pain floating above their glorious snouts, and then I’m sitting up in my sweat-drenched bed.

“A nightmare?” Sally’s sleepy voice lilts from next to me. I close my eyes and visualize my truths in fluorescent block letters to get my grounding. I’VE NEVER MET DONALD TRUMP. I AM A JUNIOR AT HARVARD. MY FATHER HAS BEEN DEAD FOR FOURTEEN YEARS.

“Yea, the Trump and Spaniel one again,” I mumble, trying to sound calm. She starts to laugh and covers her mouth with her hand. “It’s okay,” I say as I lean back on my pillow, put my hand over my diaphragm, and slowly take in as much air as my lungs will hold. My breathing slowly stabilizes. “It is kind of funny, I guess—he’s *so *Trump and the whole day we spend together is unbelievably painful. I feel almost stupid for being so gullible every time.” Then I see the dogs’ eyes again. “Sally, I don’t really understand why, but it’s seriously the scariest thing in the world when the spaniels all look at me.”

“The spaniels’ eyes specifically? Not Trump’s?” Sally, now fully awake, also has recurring nightmares and is impossibly patient when dealing with the Trump dream.

“No, Trump’s eyes are just gross. But the dogs’ eyes—they have childhood stuff in them. The pupils physically hurt me.” I’m doing some of this for effect; I’ve tried to wring the fun out of the dream by offering orations during irresponsibly lengthy Adams dining hall lunches, and I feel some of the same self-indulgence emerging during Sally’s late night psychoanalysis.

“Childhood stuff?”

***MALE AUTHORITY FIGURE MONOLOGUE-ASIDE #1: MOMENTS BEFORE 8TH GRADE GRADUATION, MAY 2009***

* Friend’s Dad: “The best way to honor your father, David—and I mean this as pure encouragement, pure positivity—is to keep being graceful as you become a man. I don’t care that I had to tie your tie before your graduation. That isn’t the point. The point is that it would take fifteen, twenty minutes tops to learn how to tie your own tie. Don’t you think it’s probably a little bit demoralizing for your mom? Do you expect her to watch a YouTube tutorial so that she can teach you herself? I’m not trying to sound harsh, seriously. Big occasions just sometimes feel like the right time for a reminder. Obviously, this is a celebration of the work you’re doing every day. Don’t forget that. But I think you yourself know that it’s time…*

**II.** **BALBOA PARK: 2009**

Balboa Park—where the baseball team practiced and the stoners smoked joints while dangling from their perches up in the Eucalyptus trees—was a three minute walk downhill from Lick-Wilmerding High School. It was the second week of my freshman year and I jogged Ocean Avenue alone in my new cleats and baseball pants, stretching out my cramped throwing arm in windmill circles. The J Train Line, which ferried the students without Mercedes-Benz carpools back to their abodes, roared down the street beside me. As the train passed, I caught a glimpse of five impossibly square-jawed junior boys laughing at my anxious preparations through its graffitied window. I tried to shrug back at them in a way that both acknowledged my lameness and also emanated advanced self-awareness, but I don’t think they saw me.

Junior teasing notwithstanding, my optimism was at an all-time high. Not only had I been cast as one of the brothers (Simeon!) in *Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat*, but Hanley Pacheco, the legendary varsity coach who had in the last year led LWHS to its fourth consecutive BCL West Championship, wanted to see me throw. Hanley Pacheco—the grizzled television salesman and Vietnam Vet who had transformed the lowly baseball team into a machine of finesse and masculine pathos. Just a day earlier, Coach Hanley had walked down the lineup of anxious, acned newbies at the end of the first official practice, scratched his graying head, adjusted his Aviators, and wordlessly pointed at me. He probably only wanted me because I was left handed and had been willing to run the field more times than anybody else. Whatever the reason for my audience with Coach, I was far more scared than I had been before my rendition of “Close Every Door to Me,” my *Joseph *audition for our flamboyant drama director Miguel. Coach Hanley was a gruff, systematic military man at a school where three different teachers in my first week of study—including two men—had suggested that world peace would only be achieved once male genitalia had been eliminated.

Coach tossed the ball back. “Try a lower arm slot,” he yelled from behind home plate. I was already throwing from the lowest angle I had ever affected, slingshotting the ball straight out from my body instead of up over my head. Every heartbeat vibrated in my shoulder as I stared at the catcher’s glove, sixty feet away through the wind-swept dust that separated the mound from home plate. A shaky glance down at my watch informed me that I was entering hour three of the pitching intensive. Hanley and the catcher were working on my two-seam fastball and I was getting increasingly excited as I saw the seams start to cut more violently across the plate and into the catcher’s ratty mitt. *This man is a baseball wizard.*

Back in the dugout, Hanley reached into a red cooler and came up clutching a handful of ice for my arm . “That was a nice first throw, kid,” he said as he gave me a taut handshake on my throwing hand that briefly brought the fingers back to life. His voice was a gravelly drawl that felt straight out of a John Wayne western, as if we had just finished corralling steer and shooting rattlesnakes rather than tweaking my windup. He grabbed my throbbing arm and gave it a squeeze that was somehow didn’t feel creepy. “Come for the varsity practice tomorrow and we’ll see what you can do. You’ve got a strong head on your shoulders and a strong arm under them.” He sounded sincere in a way that only those without a liberal arts education can. A whirlwind daydream began playing in my mind as I headed, almost skipping with joy, to the train station: Hanley crafting me into a world-class pitcher, teaching me how to skeet shoot, bringing me on one of the legendary Hawaii trips the Starting Nine on the team took every Spring...

The next morning at 8 AM, things weren’t quite as bright. I’d stayed up late writing my first English paper and kept dropping the ball in warmups because the sun was getting in my eyes. It occurred to me that I hadn’t even played a real *game *of baseball for the last eighteen months and the bulging muscles of the heavily-stubbled, senior behemoths surrounding me were taking on a decidedly violent valence. And, however much I tried to put Hanley’s moment of kindness in the dugout out of my mind, I kept looking over at the coach, with his arms crossed and a pen sticking out of his tight-lipped mouth, and imagining the positive effects his stoic tutelage could have on my whole psyche. If only I could hold myself together.

I was already panting after several minutes of field jogs with Danny Bandocci, a hulking, incredibly charismatic, soon-to-be Division I third-basemen, and the rest of the decidedly post-pubescent squad all the way to the fence of Balboa Park’s potholed complex. The team headed towards the dugout in preparation for the scrimmage that I assumed was the centerpiece of each practice. The ever-present J Church rattled by and I strained to hear Hanley’s voice over its clanging warning bell. “David, first base.” I literally almost shat myself. *When was the last time I was at first? Fourth grade? Maybe fifth grade? *Still clenching my bowels, I lingered after the other players had jogged robotically onto the field to protest Hanley’s shocking assignment.

“Coach Hanley, I’ve never even seen any of these guys throw before.” I heard balls snapping into gloves with sonic booms behind me that I’d only ever heard when rich friends took me to their nice seats at Giants games. “And they’re huge,” I heard myself say, instantly regretful of the statement, brutally conscious of my nasal timber, and fighting off images of myself as a small piggy.

“One of these guys told me you’re a *theater kid*.” He delivered this line with a ferocious grunt only equaled in my personal aural backlog by my Grandpa Jim’s vaguely senile curses towards Kamakazi pilots who had smashed into his L.S.T. Boat off the coast of the Marshall Islands in 1944. “Well, let’s see how well you can act,” he grinned as he gestured me out of the dugout and onto the hard dirt of the infield. Senior left-fielder and Student Body President, the curly-haired, pious Davy Flemming was an improbable sport-theater hybrid who was starring as Joseph in the musical and had seemingly told Hanley of my thespian exploits. He waved kindly from left field as I kicked around the first-base bag and contemplated my impending doom. The same catcher—I didn’t know his name—who had facilitated my triumphant session the previous afternoon was tossing ground balls to the other infielders. He started with Bandocci at third. I squinted and focused in on his meaty throwing hand as he scooped up the grounder and threw in my direction. The ball made a loud hiss, but I never even saw its contours as it careened into my shin and bounced away towards the mound. My leg hurt about as much as any injury I ever had experienced. After a few minutes of rolling around the infield and a cursory injury-check from Hanley (“you’re fine, get up”), I limped off the field and sat silent, biting my lip, while I seethed. I knew it was only a matter of time before Hanley would waddle over and dismiss me.

The scrimmage went on for a couple of innings while I sat and massaged the growing purple bruise on my shin. In the middle of the fourth inning, Hanley finally arrived. “Maybe you should stick to the musical theater, kid,” he said eventually. I opened my mouth to offer a defense. “Even a pitcher has to know how to field a Bandocci Bullet. Try out again in the spring, though.” He patted me condescendingly on the shoulder and strolled away. If Hanley Pacheco was the price I had to pay to succeed in the rough and tumble world of high school sports, I guessed I had to stick to Andrew Lloyd Webber.

***MALE AUTHORITY FIGURE MONOLOGUE/ASIDE #2: MOMENTS BEFORE TAKING THE MOUND IN THE SAN FRANCISCO PONY LEAGUE PLAYOFFS, MAY 2007.***

* Shortstop’s Dad and Assistant Coach of the SF Blue Jays: “You really don’t get how good of a pitcher you are, David. And I keep hearing from my son that its ‘Opera this, opera that,’ dressing up in tunics and smearing makeup all over your face. You belong on that mound! You own that mound! I know your mom is a singer and she’s probably pressuring you to follow in her footsteps. And-and-and that makes sense! You’re all she’s got; she’s all you’ve got. But I’m telling you: If you give your all to this game, it will take you far. An if you keep prancing around on that stage, what are you gonna do? Be a professional angel? Wasn’t that the last role you played? Cupid? Seriously? So get out there and throw that ball as hard as you fricking can…*

**III.** **JUDAIC STUDIES: 2007**

My sixth grade Judaic Studies teacher, Mr. Skine, was a Modern Orthodox ex-Londoner, forty years old, cloyingly conservative, and looked like E.H. Shepard’s hedgehog illustrations in *The Wind in the *Willows; portly, beady eyes, frizzed hair, and a body that mysteriously suggested impending motion in all directions. He was in his first year of teaching at Brandeis Hillel Day School, the shiny private school that had been my home since kindergarten. I was obsessed with performing well enough to get scholarship money at one of the city’s three best college preparatory schools, a process that in the increasingly elitist, tech-funded world of San Francisco was just as intense as the college “search.” So I hid my occasional frustrations about Skine’s scathing dismissals of Arabs and defenses of the Iraq War behind flawless test scores and multi-part questions about the Book of Enoch.

By midyear I had inadvertently become Teacher’s Pet, and often spent my tutorial in Skine’s cluttered office, poring over maps and laughing at his impressions of Golda Meier or Woody Allen. We even managed to conduct debates about Netanyahu’s politics and settlements in the West Bank without resorting to the histrionics I’d come to expect from many of my more passionately pro-Israel friends.

“David, I’ve seldom been able to communicate with someone I disagree with quite as much as you,” I remember him saying one day, after I had said that David Ben-Gurion’s speech on Israel’s 10th Anniversary, which we were watching on a scratchy VHS before Judaic Studies class.

“Yea, I feel the same way, Mr. Skine.” I tried to smile but couldn’t even bring myself to make eye contact with this odd little man. I was afraid I would laugh at how surreally romantic the interaction had become. We weren’t buddies, exactly (we never asked each other any personal questions) and I would never *not *feel tense when he cursed all Palestinians or argued for more dramatic military responses to Gazan mortar attacks. But he had subtly, *somehow *become my favorite teacher.

Every year, Brandeis had a charity drive where each class voted by ballot to give money to one of several philanthropies. The seventh grade had voted almost unanimously to give the money to a wing of the Red Cross focused on treating areas with the most extreme casualties from the conflict, regardless of national or political affiliations. I was on the Student Council committee that recommended the charity and had worked alongside several of my closest friends on a promotional marker poster of an Israeli girl and a Palestinian boy holding hands while a dove fluttered between them. The charity felt like a trippy locus of all my hopes—and those of many classmates—to find some moderate way forward despite the school’s clear position.

“Strange news, guys,” an especially sweaty Mr. Skine blustered as he ran into class five minutes behind schedule. “The charity your grade initially selected has turned out to be too unreliable. Some parents think the money will end up hurting Israel strategically. We’re going to give instead to an aid group that we can fully trust.” Skine’s mouth turned briefly up into a smug grin as he delivered the message. *If he isn’t responsible for this, he certainly helped move the change along.* Adi Alouf, decked out in Israeli National basketball team pullover, sweats, and headband, who was born in Tel Aviv and was part of the most aggressively Zionist family I have met to this day, raised her hand.

“My parents talked to the administration and said David and all of them were trying to give the money to the Lebanese.” *Are Skine and Adi in cahoots? Are they trying to shame me? * I was the only one of the committee in this section of the class and immediately shot up my hand to deliver some ragged defense of the organization. Mr. Skine nodded at Adi, offered some further dismissal of the initial plan, and stared right through my hand. *He sees me. He knows I’m not anti-Israel. Why would he do this to me? The little dick won’t even let me defend myself. *I kept pushing my hand up higher, even as Skine moved into a lecture on, ironically and probably intentionally, the origins of pro-Israel lobby groups. Soon I was standing and practically foaming at the mouth.

“David, please sit down. This really isn’t up for discussion and you’re interrupting the class,” he chastised. *I laughed at your stupid impersonations. I looked at the 1967 and 1973 maps.*

“You let Adi tell about her parents’ sway over the administration! You let her single me out! You’re being so incredibly unfair I can’t *believe *this shit.” I didn’t care if he expelled me.

“Principal’s office right now and a 0 in your participation grade for the week.” He didn’t change his expression while I shook my head back and forth. “**NOW**! I felt near bursting; I ran in the opposite direction of Mr. Heller’s office, out of the school’s back gate, and into the parking lot that Brandeis shared with an Armenian church down the hill. I called mom in hysterics and ran laps, tears streaming down my face, until she came and picked me up. “Why wouldn’t he let me talk?” I repeated ad nauseum with my head in my hands as mom, livid at my dramatized account, gripped the steering wheel on our way home. I thought about leaving Brandeis; I wasn’t really old or resourceful enough to conduct any meaningful research about the validity of Skine’s and Adi’s claims, so I stopped doing Student Council, put my head down for the next eighteen months of Judaic Studies class, never went to another office hours, and walked away whenever anyone tried to talk about Israel. Skine’s blank stare had made the debate pointless for me.

***MALE AUTHORITY FIGURE MONOLOGUE/ASIDE #3: AFTER I INEXPLICABLY PANICKED WHEN MY MOM WAS TEN MINUTES LATE TO MY COUSIN JEFF’S WEDDING RECEPTION AND WOULDN’T ANSWER HER CELLPHONE, JANUARY 2005***

* Cousin Norm (Best Man): Little Bro, you just can’t freak out like that. You were acting truly crazy! I know your dad died, and that’s super tough, but you’ve gotta trust the world a little bit sometimes. That’s what being a man is all about. Think about Grandpa; that dude fought in a War where shells were falling down around him all the time, but he kept his head up, stayed alert, and we’re both here because of that. So next time you’re worried about your mom, do what you can to track her down and then take it on the chin. Or you’re going to spoil everybody else’s time. *

**IV.** **MEDINA: 2005**

In sharp contrast with most of my memories from the few years succeeding my father’s death, which are shell-shocked and partial at best, my visit at age ten to my Evangelical cousins in Medina, Ohio plays back today as if a reality TV crew followed me for the whole trip and then stored the tapes in the front chamber of my hippocampus. I have access to every angle of my cousins’ sandstone McMansion, every Razor Scooter race down the steep hill in their driveway, every glance at their creationism-based “science” workbooks, and every burst of unspeakable, quasi-innocent lust at the glittering promise ring on thirteen year-old Laura’s slender right index finger. Laura, usually clad in a comely American flag tank top, led her two younger sisters and me through a week of play that was simultaneously wholesome and incredibly erotically charged—trampoline jumping contests, frog-hunting in the creek behind their house, sweaty bicycle races that ended with the two of us panting on the dewy grass outside of the Jarrett house. For a chubby fifth-grader who was used to quinoa dinners in San Francisco Victorians with my mother and Monchai, her Taiwanese bodybuilder-chef opera student, this was a confusingly salacious heaven.

I was so initially taken with Laura that I hardly paid any attention to my mother’s demure sister Georgia or her pot-bellied, mustached husband Dave. There were a few moments where the idyll had been broken; after one scooter ride, Dave had yelled awfully loudly at Laura to come help with the dinner; The second Sunday we were in Medina, however, the illusion of my narrow paradise was broken. My mom and I accompanied the Jarretts to their cavernous, televisually-advanced megachurch and watched, jaws to the floor, as jogging congregants scooped up kids with Downes Syndrome and other devastating afflictions, brought them onto the stage, and performed a stilted disco. An arena rock-style band providing the soundtrack, soloing dramatically while a large screen above them flashed clip-art of crosses, American flags, and golden babies bathed in ethereal light. I glanced to my right and saw the Jarretts, eyes closed and arms interlocked, swaying along to the beat. Dave, whose nasally commands and holier-than-thou rhetoric had hitherto been drowned under Laura’s sweet birdtones and black jorts, now came into sharp focus. His white knuckles were gripping his family member’s shoulders, and when Laura tried to go to the bathroom he tugged her back into formation. *He’s being a tyrant*. A vivid montage of initially half-registered Dave barkings (“Don’t talk back!” “Say your prayers!” “Bedtime now!) invaded my aural center and all but drowned out the God Band’s slightly flat rendition of Creed’s “Higher,” now on its sixth and final chorus.

“Is Uncle Dave making them do this?” I whispered to my mom after I wrote her a note in a laminated, CGI-illustrated hymnal that read “THEY ARE CRAZY! HELP! HELP! CAN WE TALK IN LOBBY?”

“Of course not, David.” My mother, who had been beaming the whole week at the Laura-assisted, improbable symbiosis between my burgeoning ultra-progressivism and the Jarretts’ fascism, was doing her best to stop the schism.

“But Laura is *so *normal and funny and he’s always loud and bossy and I *know *this is his fault.” I felt the tears well up and jerked anxiously around to see if any of the Christ-zombies were watching this little visiting Baby Jew have his nervous breakdown.

“Dave and Georgia clearly have different expectations than I do,” my mom preached calmly as she held my hand. “But they are being generous hosts and we are their *guests, *and unless Dave does anything mean to you we have to let them parent the way they want.” I calmed my conspiratory mind as we walked around the rose garden outside and watched the SUVS zoom by on the pristinely blacktopped boulevard that bisected the church’s endless parking lot. *I don’t have a dad. When he was alive he was always sick or maybe he would have been more like Dave. I don’t know how dads are supposed to act. Maybe he’s normal.*

Back in the family’s gigantic kitchen that evening, however, I couldn’t stop looking at Dave as he tracked his children’s dinner chores with laser eyes. My mom was seated with Georgia at the round, mahogany dining room table, engaged in a guffaw-heavy Scrabble match while I pretended to read a later volume from Walter R. Brooks’s *Freddy the Pig *series in a cushy armchair in the corner. Every third paragraph, I would go over what I knew about Dave as I watched him pace and offer terse instruction out of the corner of my eye: Born to a zealously religious family in Nebraska; married Georgia when he was 21; converted her from the relaxed Presbyterianism that my mother and her five siblings had grown up with; was a plant manager for 3M and moved his family around every few years; could go from the gentlest man in the world to a militarist at the slightest indication of a threat from any of his kids; believed in some truly wacko, arch-macho nonsense that even *I *as a *child *could understand was damaging to poor Laura and her brainwashed sisters!

My mom screamed an operatic High C as Georgia laid down a decisive bingo on the board. “Well, it’s not like I’m *ever *dramatic!” my mom said sarcastically after all of the kids and Dave dropped what they were doing and stared at her. Mom and I joshed theatrically about her operatic volume all the time back home, so I figured why not start a little scene.

“Oh *never*, Mom!” I commented with dripping sarcasm.

“You **DO NOT **talk back to your mother,” yelled Dave as he bee-lined for the armchair. Laura had her head down and my mom was frozen with her hands in the air, as if she were about to intervene but didn’t know if there was a tactful way forward. I didn’t think specifically about provoking Dave’s wrath, but I also was more excited than shocked when all of the Jarretts’ faces went blank and my mom anxiously scanned the room. *I can’t let him crush me like this. *

“I wasn’t talking back to her, I was agreeing with her!” *How far could I go? *“Oh, sorry, I guess I’m talking back to you now. That’s probably bad, too, right?” I let out a laugh-bleat as I saw the terror on everyone else’s faces. “Can you even *talk *to somebody without talking back?” My heart was thumping; a bead of sweat was forming on Dave’s forehead and his usually placid, bushy moustache was quivering like a spastic caterpillar.

“You and I are going to have a talk, young man.” He grabbed my arm and practically lifted me out of the chair. I can still see *Freddy and the Spaceship *dropping slow motion onto the pink cushion. A blur of faces: my mom, still frozen; Laura, whose shame I frantically imagined hid some sort of rebellious excitement; Georgia, just as pleasant as ever. We were out of the dining room and into the pantry before I could protest.

Dave drilled holes into me with his eyes harder than anyone I’d ever met. “Buddy, buddy, buddy.” He was pleading. My palms began to well up with sweat and I tried to pretend Dave wasn’t there, focusing my mind instead on memorizing the labels on the fruit roll ups, the pancake mix, and the English muffins. *Don’t even acknowledge his presence.* “I know you lost your papa, but you need to learn how to be a son.” *You have no idea what I’ve been through. You don’t know what I’ve done for my mom. You are what she moved to San Francisco to avoid. *

“I’m a better son than you’ll ever be a dad,” I mumbled, before fake whispering, in my most exaggerated voice of alarm, “Oh shit...I guess I just talked back again.” I hoped he would hit me and had sick visions of myself running into the dining room, nose swollen and purpled, while he stalked out behind me cackling and speaking gibberish as his tongue dangled out of his mouth at an impossible length and the whole family ran to the hills. Instead, he began to softly and tearlessly cry, his head bouncing up and down like a pious Jack-in-the-Box.

“I really care about you.” He sounded more like Barney than Billy Graham. “And I know you’ve been through a lot. I just want to do what I can to help you grow up strong.” *No God speech? No Indian burns? *I felt somehow cheated; I’d expected brutality and had been treated to a sad parade. “I know your house isn’t like my house, but you have to play by my rules for the next few days if you want to stay here.” He took a long pause to see if I had some smart-ass retort, but I was too shocked by his honesty to even blink. “And try to *learn *something about being a man.”

I still kind of hated Dave Jarrett and I still think today that his whole conceptualization of the world is objectively dickish, misogynistic, “what’s wrong with our country,” et cetera. But in his moment of forced parenting, he took the pretentious fight right out of me. The last few days we were in Medina, Dave had me mow the lawn, wake up at dawn with him and go see 3M, sit through three more heartbreaking talks about respect. I didn’t fight back and only engaged when I needed. The night we flew home, I gave a glum farewell to Laura, shook Dave’s hand as hard as I could, and watched out the window of the plane all the way to SFO, wondering how I could have been stronger and inventing sons and dads for the little speckled towns 45,000 feet below. I was about as sad as I’d ever been.

***MALE AUTHORITY FIGURE MONOLOGUE/ASIDE #4: MY THERAPIST, A DAY AFTER MY FATHER’S DEATH, APRIL 2002. ***

* Dr. Stein: You’ll always have the memories, David; the songs you shared, the hugs he gave you, the way he looked before he got sick. Keep those close. Don’t forget them. Does that make sense? He will always be your father and you will always be his son. But don’t be afraid to find other dads. Don’t be afraid to let people help you. You’re a big boy. He’s always going to be in your heart, no matter what. *

**V. TRUMP’S SPANIEL’S PART TWO: 2016**

Sally indulges my late night ramble and sits at my desk sketching Dave Jarrett’s mustache on a Post-It. “So you’re afraid of the spaniels because they represent the judgment of all these aggressive guys who have tried to mentor you and end up being mean?” Her monotone suggests she is disappointed by the admittedly lame payoff. Was that all I was trying to say? It’s not like I feel that torn up about my rejections from Evangelical Christianity, AIPAC, or being a first baseman.

Out of nowhere I’m crying, mostly out of embarrassment at how these supposedly traumatizing encounters are so condescending and whiney. Kids are being ruthlessly abused by actual tyrants all over the world, and here I am bemoaning a few awkward flare-ups with men who were genuinely just trying to help me develop a thicker skin. So what if we disagreed about macho shit; tough luck, kid. The privilege litany begins, the perpetual guilt games are spinning into over-drive. I give up on trying to validate the fear that the Trump dream brings up. I have a great line that I had originally used in one of my dining hall orations (“It’s not that I can’t handle the spaniels looking at me, it’s that I can’t handle not being able to look back”) and, as we crawl back into bed, I’m just about to say it in a sort of dark attempt to make Sally laugh and dismiss the whole thing. Then, as can so magically happen with dreams, I remember a part of the action that I have forgotten.

In the corner of Trump’s living room is a portrait that I never fully see. As I float away towards waking, right before the dogs turn towards me, I jerk my neck to try to fill in the blanks. *Is it a portrait of me with the Trumps? How trippy would that be. Dreams are insane. *The portrait unblurs enough for me to tell that it’s my actual father, Daniel Kurlander; I can see the mischievous, Cheshire Cat curve of his smile, a look that I’m not sure I recognize from pictures or from real life. I’m flooded with sudden, crushing guilt that I had ever forgotten him, even in this fleeting dream. But even though I see that it’s Daniel, my dad, I can’t make him come into focus. Only the spaniels are crisp, and Trump’s devilish guffaw. I try desperately to conjure up some coherent image of the man I had lost, whose voice I so want to use to drown out the pain of what his absence wrought. All I could find was a snippet, but I managed to calm myself down and fall back asleep.

***MALE AUTHORITY FIGURE MONOLOGUE/ASIDE #5: MY FATHER, SHOWING ME HIS RUBBER SOUL LP, 2000.***

* Dan Kurlander: Davy, look at the stretched-out faces. They were all about being clowns, you know. It goes George, John, Ringo, Paul, left to right. Electric guitar like my red one, rhythm guitar like my yellow one, drums, and bass guitar, which is like a normal guitar but without two of the strings. And they all sing on this record. There are something like nine other ones. Actually, I guess they all sing on all of them. Anyway, I hope they mean something to you and help you find what you love a little bit. I’m going to put the record on and come right back. Daddy has to go get dressed and try to get well, Davy Bear. *

Archived Notes • Summer 2016

Dr. Toni Morrison delivered six lectures on campus this spring as the 2016 Charles Eliot Norton Professor of Poetry. She has published 11 novels, most recently *God Help the Child *(2015) and various works of non-fiction criticism. Dr. Morrison won the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012, the National Humanities Medal in 2000, and the 1993 Nobel Prize in Literature for giving “life to an essential aspect of American reality.”

Prof. Morrison generously agreed to meet with Fiction Board member Chloe Brooks on April 13, 2016. Here is the transcript of the conversation.

ADVOCATE:

Throughout your magnificent lectures you turned to various texts, from a medical journal to a Flannery O’Connor short story to your own novels, to illustrate the concepts you discussed—from the role of the stranger to the "color fetish." In your last lecture, you connected contemporary history in your discussion of globalization with a specific literary work you admire, in such a way that one seemed to explicate the other, not in a direct but comprehensive, productive way. Your own works all embed literary narratives within specific historical moments and contexts, but the relation between the two does not stop at mere historical detail. How do you view the relation between imaginative literature and historical events? How does the former, with all the freedom afforded fiction, alter the “picture” of history for the reader?

Dr. Toni Morrison:

I'm up to the last part. But on the penultimate question in there about the relationship between history and literature, I think there's data, and then there's information that comes from data, and then there's knowledge that comes from information. And then, after knowledge, there is wisdom. I am interested in how to get from data to wisdom. And literature, it seems to me, is wisdom. Some literature is knowledge, some is just data. But if I can get a "happy" ending—which is when for the characters I'm writing about, something happens that they move from wherever they are in the beginning to knowledge or wisdom, they know something they never would have acknowledged or realized if it hadn't been for my book—that for me is what literature does.

I did an introduction for Primo Levi. I knew his work, I didn't know it all, but I knew enough. And I read some things that people have said about him, mostly echoing the horrors of the Holocaust. And that was there, but what impressed me enormously about his writings was how he always found humanity, always, he always looked for that, within that context. And what he wrote about are the people who gathered together to save somebody, or the people who *shared* some food, or the people who died with something in their mouths that they said, that impacted him. Actually, I don't think he gave a shit about the guards. He never talked about them. They were not even people to him—they were like robots that kill people. And they were irrational. Like, he took an ice cube to suck, and the guard came and took it away, and he said "why, why'd you do that?" And the guard said, "There are no why's or answers here." So that was it. They were almost non-thinking. But the people, the humans, were the ones in the barracks. His poems were not so even-keeled, but his writings were.

ADVOCATE:

It's possible to write about evil in an interesting way . . . I think of Hannah Arendt, for instance.

MORRISON:

Yes, she does, but she says "the *banality* of evil." That's right. She's on it.

ADVOCATE:

You spoke about that during a question and answer, about evil being boring. Is that it—that evil is unthinking?

MORRISON: