Winter 2015 - Possession Issue - The Harvard Advocate

Features • Winter 2015 - Possession

When he called from Italy to tell us, he phrased it like this:

“You’re getting a stepmum!”

Even then, in the midst of the spasm of joy that followed, I remember thinking it was a strange choice of words. Not *I proposed to Sarah*, not *We are getting married*, but *You are getting a stepmum*, as if she were a toy we’d requested after seeing it in a TV commercial. There was, within it, the promise of newness, of a whole different person—yours to take home today!—which is, mind you, what people used to think actually happened when women got married.

And, to some extent, it is what happens. The next summer, in the somewhat inexplicable presence of a Catholic priest, we all said goodbye to Miss Wietzel and hello to Mrs. Seresin (a person my own mother, in her brief marriage to my father, never chose to become). More thrilling for my younger sister and me, though, was saying hello to our very own stepmum.

For a long time we had begged them to get married, not because marriage would really change anything, but because we’d wanted so badly to have that word, stepmum. To hold it and wield it in our hands. This is the kind of impulse that comes from growing up in a family like ours: lopsided, always requiring explanation. For four years we’d struggled to know what to call her, scavenging for some way to summarize what she meant to us and always coming up empty-handed. “Dad’s girlfriend” may have been accurate, but could not describe the person who knew the names of all my teachers, who accompanied me to grimy bathrooms in foreign countries, who was the first person I told when—secretive, shy, 11—I got my first period.

Not only that, it dislocated our connection by a degree. “My dad’s girlfriend” does not contain the undertone of ownership we all, on some level, crave in our relationships. My best friend, my fiancée, my roommate, my teacher, my stepmum—myriad bonds tied together by the same infantile word: mine, mine, mine.

“Do you like her?” people ask, often grimacing, picturing Cinderella.

What to say to this? She understands how to talk to people—to me—like no one else I’ve ever met. In sixth grade, my darkest hour, I would spend hours in my room playing loud and terrible R&B on my CD player and crying myself to sleep, and she loved me even then, even though I was objectively horrible. When people ask me if I like my stepmother, I want to say not “yes,” not even “YES!”—I want to tell them it’s a ridiculous question.

***

On the first night of the first trip we took together—a short and low-stakes weekend in the country—my sister Ruby grew suddenly flustered, turned to Sarah, and yelled:

“*You* can’t be Papa’s girlfriend. *I’m* his girlfriend!”

Ruby at that time was five years old and prone to wearing our dad’s baseball caps on her tiny head, where they resembled upended boats. None of this prevented her from seeing herself as competition for my stepmum, who was 23, 5’11”, and modelled for Tom Ford at Gucci— and, among these other advantages, not my father’s biological offspring (though a whole string of waiters over the years have assumed otherwise).

This episode is one of our family jokes. Today, when we laugh about it, it is with that particular ruthlessness of families, a laughter that promises catharsis from future conflict by confirming that our old traumas are truly dead and cold.

Sarah, on the other hand, has a relentless capacity for sympathy. One way in which she sticks out: She is never as thoroughly cruel as we are.

“You must have felt like I was stealing your dad.”

This is probably true. But it’s funny, how we talk like this––as if the people we love are things that can be stolen.

***

“I don’t know what’s happened to you. But remember: There’s no problem too big for Jesus.”

I had been nakedly sobbing for 13 subway stops when the elderly woman sitting opposite me decided to pat me lightly on the knee and tell me this.

“Thank you,” I sniffed. I more or less agreed. The imminent deadline of my senior year extended project—a play I’d written, for which I’d planned to compose an as-yet-unfinished score for solo cello—was likely not too big for Jesus. But it was indisputably too big for me, a fact I remembered immediately, the tears streaming again.

When I arrived at the house that, at this point, Sarah still shared with my dad, my face was swollen and twisted as a red balloon animal.

“Sit down,” she said. “Let’s sort this out.”

My parents—all three of them—are of the “hands-off” school of child-rearing. This is a fact for which I will always be grateful. I recently watched a documentary that chronicled the life of a bourgeois black kid in Brooklyn whose accomplished parents would circle and criticize him every night as he struggled to get through metric tons of private school homework. Watching with horror, I understood properly for the first time what people mean by “helicopter parent.” Seeing these two adults hover and hound and peck at their son, however, I could not help but feel a more accurate term might be “vulture”.

On the rare occasion that my own homework would lead me to sit morosely at our kitchen table and weep, my mother always provided the same, usually sage advice: “Just don’t do it.” My dad, connected to my academic life only in the third degree, never knew these moments even occurred. When he called from abroad and asked how school was going, it was never during those occasional blips when I couldn’t honestly tell him it was great.

Some days, though, I did need help.

“Here’s a pen. Write down a list of everything you have to do.”

I obeyed. Once the list was complete, Sarah looked at it.

“Right. So now you have to do it.”

“I don’t know if I can.”

She shrugged, but not in an unkind way. No—this shrug was more like a gift.

“I mean, you just have to. That’s all there is to it.”

There is something beautiful about British pragmatism, a method of problem-solving guaranteed to cure even highly-advanced strains of emotional hysteria. Neither of my biological parents are British, but Sarah is, and though I generally feel rather estranged from the culture in which I grew up, at this moment I could have got down on my knees and kissed the Union Jack.

But it was more than just that. I needed my stepmum’s help at that moment because of how little she cared— how little she was capable of caring. Make no mistake: We have come to love one another unconditionally, a love grown from the ground up, the way a colossal oak tree blooms from the tiniest of seeds. Yet unlike a “real” mother, Sarah does not see an image of herself in me.

I used to think about this during parents’ evenings at school, which always reminded me of the first scene of *101 Dalmations*, in which Pongo watches dogs and owners who resemble each other in comic ways—the same sloping walk, the same fluffy hairstyle—parading together down the street. There was something in the eyes of the parents that betrayed a feeling that each triumph, each sting of embarrassment, belonged as much to them as to the child being discussed (hence the evening’s unfailing atmosphere of high drama).

Mothers and daughters are especially susceptible to this conflation of identities. I have a friend who starts dieting a few weeks before every vacation in order to make sure that, when she gets home, she’ll fit into her mother’s clothes. My relationship with my own mother has, thank God, never come close to resembling that one. Yet sometimes, in the middle of the simplest conversations, her eyes glisten—with tears of pride, concern, or simply the ferocity of maternal love.

Writing on pregnancy in *The Second Sex*, Simone de Beauvoir reflects: “[The mother] experiences it both as an enrichment and a mutilation; the fetus is part of her body, and it is a parasite exploiting her; she possesses it, and she is possessed by it.” It is from this intense reciprocity, this place of possession, that my mother’s tears flow. And it is for this same reason that, when I have spent 13 subway stops sobbing about a minor problem, I go to see my stepmum.

***

Since I’ve been in college, we’ve made a tradition of drinking bison-grass vodka at her kitchen table and talking until I miss the last train home to my mother’s apartment. This winter, when I call to arrange this, she says my half-sister, Marnie, has been sick with a consistent 109 temperature and they’ve all been trapped inside for a week.

I picture the three of them confined indoors: my half-brother crazed as a puppy to get outside again, my stepmum celebrating New Year’s Eve alone while Marnie sleeps in the room next door, her lungs rattling like little radiators. I tell Sarah I will make us dinner.

This is the kind of thing I relish about growing up: making promises like this, embarking on a special trip to the grocery store to buy fresh herbs and tahini, and refusing Sarah’s offer to pay me back. It’s a particularly adult way of showing love, a performance I’m still in the process of learning.

When I think about how families are supposed to love, my mind drifts to nouns: a good wife, a good parent, a

good daughter (that the nouns are skewed feminine should not require explanation). Such phrases litter our culture. *The Good Wife* is a popular CBS television show; Simone de Beauvoir herself called her first autobiography *Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter*. There is no such thing, however, as “The Good Stepdaughter”—not even “A Good Stepdaughter.” There is only me, insisting that Sarah sit still while I look for an ice-cream scoop, opening all the wrong drawers.

***

Often, when people talk about non-biological parents—step, adoptive, or otherwise—they speak in terms of a special connection that’s supposedly missing. I won’t deny such a connection exists. As a kid I was once involved in a horse-riding accident, and before my best friend’s mother (whose watch I’d been under) had a chance to let my family know, she got a call from my own mother, miles away.

“Sorry to be paranoid, but is Indiana alright? I just got a weird feeling.”

Regardless of the unconditional love that has over the years steadily blossomed between my stepmum and me, regardless of the fact that I consider her as much a parent as my own dad, I doubt she would ever experience this kind of cosmic tug. Here’s another example: When I was nine, I fell off a boat. Within seconds, my father, the only person capable of commanding the boat, jumped in after me. The look on his face is still frozen in my mind, and there is no way to describe it other than stupid: eyes round as coins, lips pursed single-mindedly.

All instinctive love is stupid, and without it, none of us—not one dumb, devoted mammal on God’s green earth—would survive. Yet its consequences can be disastrous. For just as one child was heroically saved that day (more so by her lifejacket than her father’s love, but that’s not how this story is told) the other was left stranded on a boat, yelping, accompanied only by a stepmother who didn’t know how to sail.

This story, too, has become a family joke, albeit one we approach with more caution. For years afterwards it remained charged with the potential to provoke an argument between my stepmum and my dad.

“It’s the *one* rule of sailing!” Sarah would cry in exasperation. “If you’re the only one who can sail, you don’t abandon the boat!”

After the birth of my half-sister, however, her anger subsided.

“I do get it now,” she tells me, a tinge of disgruntlement lingering in her voice. “It was still a terrible idea to jump in after you, but I get it, because I would probably do the same.”

What actually ended up happening was, while my dad and I bobbed fairly contentedly in the warm water, my stepmum and sister zoomed off toward the horizon, propelled by a suddenly violent wind. Sarah—25 at the time, only three years older than I am now—had no idea how to even begin slowing the boat, let alone turning it around. She didn’t even know the three-digit emergency number, the only means of contacting dry land. Meanwhile, the shoreline withdrew, and the wind swallowed my sister’s screams.

After an undetermined stretch of time—to my dad and me, minutes, for Ruby and Sarah, years—a yacht cruised by. Restraining her panic, my stepmum managed to communicate with the two experienced sailors aboard, slowly regain control of our boat, and eventually steer it back toward my father and me, who were still buoyed by our life- jackets and amusedly comparing our plight to the movie *Open Water*. With some fumbling, we climbed aboard— me first, then my father—into an emotional thunder- storm of relief, fading hysteria, and furious glances.

Not for the last time, my stepmum had rescued me.

Features • Winter 2015 - Possession

Étienne Balibar is a French philosopher. As a student of Louis Althusser, he coauthored the influential *Reading Capital*. His extensive writings have analyzed the nation-state, race, citizenship, identity and, most recently, the problem of political violence. Balibar is a visiting Professor at Columbia University’s Institute for Comparative Literature and Society. *The Harvard Advocate*’s Art Editor, Brad Bolman, sat down with Balibar on the occasion of his lecture, “Violence, Civility, and Politics Revisited,” at Harvard’s Mahindra Humanities Center on November 5, 2014.

*I was wondering if you could speak about your work through the lens of possession. You often write about citizenship, which is a matter of being possessed by a nation or government, but also in terms of possessing rights, country and space.*

This year, Verso published* Identity and Difference: John Locke and The Invention of Consciousness*, a commentary on John Locke’s* An Essay on Human Understanding*. This essay is a classic, an absolutely fundamental reference for discussions about personal identity. I’ve always had, perhaps a very continental idea, that a philosopher’s metaphysics or epistemology and his politics and political philosophy must have very intimate and intrinsic relations. That’s the case for anybody from Plato to Spinoza. I found analogies between [Locke’s] theory of personal identity and his political theory, where individual liberty is famously based on the notion of self-ownership, which he called “propriety in one’s person.” So on one side, he has a basic notion of “possessive individualism.” And on the other side, a theory of autonomy and conscious identity where the only basis for an assignation of identity is the consciousness that an individual has that his thoughts, memories, etc. are really his and not somebody else’s.

*For Locke, then, individual identity is fundamentally a matter of asserting one’s control over one’s thoughts. How does he explain this process? *

How do I know that I am myself, and not you? That’s because my thoughts are *mine* and your thoughts are *not* mine. And I can also be sure that my thoughts are not yours, you are not owning my thoughts—owning is an extremely interesting category. On the other side, you have the idea that one’s individual, social and political autonomy comes from the fact that something is, so to speak, inalienable. So it’s “propriety in one’s person,” which Locke develops by using a formula that was central during the English Revolution, one by which English revolutionaries, including such radicals as the Levelers and so on, would claim they were independent from the state. It’s the formula that “propriety in one’s person” is one’s life, liberty, and estate, a very interesting formula which resonates with *habeas corpus* and a number of issues.

*Because in the latter example, at least, it is a matter of maintaining ownership of one’s own person against a sovereign power.*

Yes. And to continue with your theme of *Possession*, something interferes, so to speak, an extremely long and bizarre part of Locke’s chapter [which] is devoted to counterfactuals—cases in which the criterion that he proposes yields results that are counterintuitive from the point of view of what most people think to be the identity of a person. Cases in which there are multi- ple personalities or split identities, including an extraordinary passage which seems to directly anticipate and foreground [Robert Louis] Stevenson’s famous novel* Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde*. It’s a question of somebody who does something—he calls the two personalities the Night-Man and the Day-Man, and the Day-Man, not by chance, is an honest man, while the Night-Man is a criminal—and the question is whether the night man, who has absolutely no memory of the crimes that were committed during the night by his alias, should be held responsible for these actions. The logical answer is no.

*Because they are different men to some degree. The parallel with Stevenson is fascinating.*

Then there are other cases which are more similar to problems of possession, precisely, or *invasion*, I would say, of one’s identity by somebody else’s thoughts or powers, which are not cases of *split* identity but cases, so to speak, of *fused* identities. So Locke invents a mythical example. He says, “What if I could find among my memories the thoughts of somebody who has lived centuries ago?” or “What if Plato?”—that’s wonderful because it seems to anticipate [Jacques] Derrida—

*And particularly his essay “Plato’s Pharmacy,” perhaps also his use of “specters” and “haunting” to describe the function of speech and memory.*

Yes, of course. So he says, “What if Plato did not simply interpret or transmit Socrates’ thoughts, but actually had Socrates’ thoughts in his mind?” I find this extraordinary because, though I’m not superstitious myself, I think what we learn from psychoanalysis and other deep psychology theories, etc, is the fact that after all it’s not so easy to distinguish sometimes between your own thoughts and others that have been somehow adopted. So it appeared to me that Locke was a key figure to investigate in the classical era, and at a moment when philosophers of his kind are supposed to be pure rationalists, if you like, in fact a whole array of questions involving the two sides of this relationship: membership, on one side, or relationship to others; and possession, or property, or appropriation and belonging on the other side.

Now I’ve also reached the moment when I want to say something about not only individualism, but the construction of the abstract individual who is supposed to be the bearer, one would say, of rights—and that includes rights to possess and to acquire, in Marxist terminology, the bourgeois “Discourse of Modernity.” This combines two sides of the problem: Why is it necessary to be able to possess rights and things, but also knowledge, etc., to become a normal or a full member of the civic community? And how can we understand that the kind of legal and social normalcy or normative framework that was progressively built in Europe, and therefore in the world during the classical age, especially in England and France and the United States, has a very strict correlation between membership in a civic community, on the one hand, and being a bearer, being defined, I would say, as a universal person by one’s capacity to possess and acquire, again, not only things, but one’s self, one’s labor force, one’s knowledge?

*To be this subject that constantly seeks to possess and master both itself and everything around it. *

Of course this is fascinating in many respects: first, it involves that you accept very strong constraints, I would say, or logical axioms both concerning community and concerning individuality. And then it is also interesting because, as classical theorists knew, there are limits. At some point you reach a limit where it’s no longer reasonable to have this absolute right. Intellectual property is an obvious example. Philosophers like Kant and Fichte wrote seminal essays on how to define intellectual property and secure the rights of one individual over his thoughts, his work. What is it that you exactly own? What is it that ought to be protected? What is it that should not and could not be defined as an object of absolute individual appropriation without catastrophic consequences? Is it your thoughts? Is it your words? Is it your style when you write something? And so on. Where does it cease to be rational?

And of course these things are, today—I’m not an expert on that, but legal theorists and others are permanently concerned with it not only because new technologies profoundly modify the ways in which thoughts are shared but for that reason also invented or appropriated—subjectively, the relationship of individuals to their own ideas is changing rapidly. If you’re on a chat on your computer, there are words and ideas that flow permanently and circulate among different persons. It’s an incredible acceleration which in earlier times would take much more time and, so to speak, give you the time to identify with your thoughts, etc.

And then there are the pathological limits, I would say. It was of course on purpose that I used the formula that what classical philosophers and, in fact, the law itself characterized as this correlation between possessive individuality and civic membership is a sort of normalized vision or representation of the human. I’m not contesting that we need normalized forms, except they’re not exactly the same in all cultures and that’s an important point. What transgresses the limits of normality is, in some cases, not only as important or interesting as the normal itself, but it is also something where it’s not only a question of rights that individuals have, but it’s also a question of what kinds of constraints and, in some cases, *violent* constraints they’re subjected to and they can exert on each other.

*There was one moment in your lecture yesterday when you spoke about “cruelty” very close to the beginning. You mentioned the way it stretches or challenges the difference between subject and object and the form of “violence” that might exist between those two categories. The two examples that you gave of objects, and violence done to or by objects, were “Art” and the “Museum,” and I thought you were maybe referencing Steven Miller’s *War After Death—

It’s a beautiful book. It’s a wonderful book.

*I thought of the Buddhas— *

—of Bamiyan, yes.

*And so I wondered if you could develop this idea further, in terms of how you think about violence and the object in relation to art, and perhaps the museum, in particular, which I thought was an interesting example— *

Not only was it quick, but it was provocative and perhaps reached the limits of absurdity because I simplified [Miller’s] presentation enormously. Because his presentation involves some considerations on not only the question of death, but the way in which you apply the adjective “dead,” which could trace back to our previous discussion, and because the criterion of something being *living* or being *dead* suddenly plays a role in every discussion of possessing, appropriating, mastering, and so on. But of course “dead” has two different meanings in our languages: either it’s the result of the action of killing, so what is dead is what used to be alive, or dead means it’s not alive because it was never alive. So you say that this table was a *dead* object which apparently doesn’t mean the same thing as “I’m sorry you asked about my father’s health, but he’s dead.” You know?

Some things are dead because they died, but others are dead because they never lived. Now the interesting thing is that progressively you discover there are all sorts of important objects which are in a dubious or intermediary situation between these two poles. And we are used to saying “This is a metaphoric use of the term.” But first, again, if you move to another environment, things become rapidly, extremely different. So of course our rational—and I have to say Eurocentric and colonial—way of looking at things easily pushes into *superstition*, *fetishism*, etc. every idea that statues or objects are alive or dead. But we have our own fetishism, as Marx perfectly well knew and others explained.

*The “queer” agency and life granted to the commodity. *

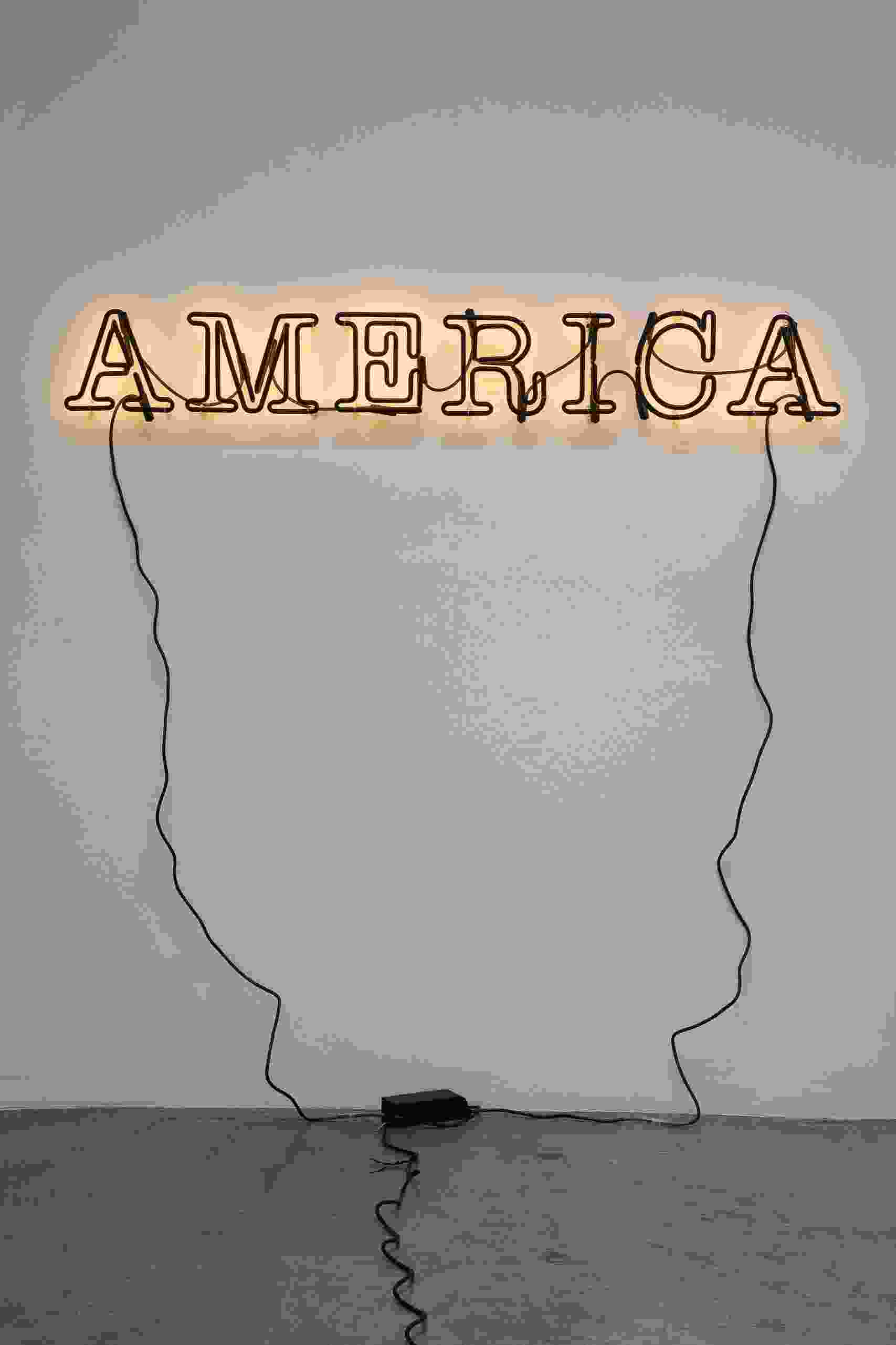

And art finds itself in a strategic situation also because we think that art, I mean we speak of “live” performances, the fact that painting, writing, taking pictures, etc. are activities which either bring to life or create life, so to speak, or, on the contrary, kill, in a sense, their objects. That’s again metaphoric. In a famous passage the poet Mallarmé explained that the word, in a sense, kills the object. You see anthropologists today who pay great attention and respect to the idea very broadly shared and accepted among Native American Indians, for example, whose religious or cultural objects have been taken in one way or another and transformed into a museum object—that they have been *killed*. You can extend that and say they are in a cage, or have been killed, or have been held hostage.

And then, if you admit that life has a symbolic dimension and art is an essential discourse or practice to reveal that symbolic dimension, you no longer find it extraordinary or absurd to extend and take seriously such categories as imprisoning, or enclosing, or killing, etc. to cultural objects. There are moments in which we are all angry and we think that the museum is sordid—while it can be beautiful, it can be extremely refined and scholarly—but some artists would say, “My works were not made to be put in a room, in a museum. They were made to circulate.” Which in fact of course leads to another form of appropriation and possession.

Features • Winter 2015 - Possession

Ah remember walkin along Princes Street wi Spud, we both hate walkin along that hideous street, deadened by tourists and shoppers, the twin curses ay modern capitalism.

–Irvine Welsh, Trainspotting

There is geometry in the humming of the strings. There is music in the spacing of the spheres.

–Pythagoras

Peacock Princess

The dancers hop around the stage, dressed in polyester costumes, accompanied by the music of electronic lutes. The women are uniformly attractive in their false eyelashes and youth. Most of the men look mediocre, but two tall chiseled fellows keep pushing their way to the front of the ensemble, aware that they’re the stars of the display.

Now the dancers flit their way backstage for a quick change. Soon they’re back, some in flower cuffs that radiate petals from their necks, others in imitations of Miao, Hani, or Dai ethnic dress, beaded, tasseled and zipped up. It’s a production of “The Peacock Princess,” a Dai folk tale that parallels “Swan Lake,” in the largest indoor auditorium in the town of Xishuangbanna, Yunnan province.

The audience is overwhelmingly Han Chinese, and most of them are tourists. The town follows an official demographic policy of “three-three-three”: one-third Dai, one-third Han, and one-third other minorities. The province is known for having 25 of the People’s Republic of China’s 56 officially recognized ethnic groups. As tourism in China booms, however, more and more Han Chinese flock to so-called minority attractions to watch ensemble performances, tour ethnic villages, and eat and drink.

“Han run pretty much everything,” says a cab driver, a transplant from Jiangsu province. “The local people are too lazy.” After a moment, he reconsiders, “Well, not exactly. The Dai king is still a big shot around here. The government couldn’t build that new airport until he gave the go ahead.”

Indeed, the locals are far from complacent in this business. A tour of a traditional Dai village is often a classic fool’s gold scam. In this case, the gold is silver—a young woman brings a group of tourists into her family’s traditional Dai home, raised on wooden stilts, in an ostensible cultural exchange that ultimately turns into a marketing pitch for fake silver trinkets.

Not that tourists aren’t easily duped. At the end of her spiel, the woman brings out a black velvet-draped table hitherto hidden in a corner. She whips off the cloth to reveal gleaming silver bracelets, belts, cups, and bowls; a king’s ransom in ancient times. The tourists descend on the shiny things like magpies.

The Chinese tourism business is the business of spectacle. The production of “The Peacock Princess” imitates the most lavish of Broadway musicals or Disneyland shows, but without a multi-million dollar budget. It’s no Tchaikovsky ballet. Men in cartoon elephant suits pretend to play fake gourd flutes, while music emanates from speakers. The flute syncing is impressive, but when one player misses a beat, he smiles sheepishly at the front row and continues pretending. The show must go on.

Despite the peacock glitz and glitter of the production, certain movements emerge like jewels from sand. The dancer who plays the Peacock Princess is a slender, sickle-backed young woman. Her white dress billows from her body as she arcs around her prince in uncertain pirouettes. She circles toward him; their fingers nearly touch.

Bread Loaf Bus

A ubiquitous form of transportation in China, next to the classic motor scooter, is the bread loaf bus. Named for their shape, the vehicles are precariously top-heavy and so often tip over that their sale has been outlawed. Many buses, however, are still in service as tour vehicles. Prized for their large carrying capacity, the buses zoom cheerfully down mountain roads. I could swear I’ve seen their wheels leave the ground, but the passengers inside usually provide a heavy enough ballast against catastrophe.

Inside the bus, the tour guide, if he is a good one, is a combination of travel agent, marketing representative, and comedian. Our guide, the son of a Han father and Dai mother, quips trivia about the local culture. I wonder if he ever gets tired of repeating the same stories day after day, but he seems animated, if rehearsed. He’s a thin man with crooked teeth. When he walks down the bus to collect our ticket fares, golden rings slip and slide on his bony fingers.

“This is such a good deal,” he tells us. “If you had bought the tickets on your own, it would have cost two times as much.” We take him at his word.

The passengers in the bread loaf bus are a decent representation of the Chinese middle class. An older father tells us proudly that his children, a daughter and a son, are both enrolled in “international” schools in Shanghai. Two friends, women in their early thirties, trade iPhone photos on the WeChat social network. A family with an adult daughter hardly says a word the entire ride. Two families are accompanied by sets of grandparents.

The tickets in question afford entrance to a Dai Water Festival show. According to our guide, the Dai celebrate the New Year (in April by the Gregorian calendar) with a water fight from dawn to dusk. Capitalizing on this novelty, daily New Year’s Water Festivals have sprung up around the city. Before we make it to the show, we make an obligatory stop at a tourist-centered jewelry store, a common but unadvertised itinerary item on Chinese tour trips. For a commission, the tour guide drops his passengers off at a jewelry store in the middle of nowhere for an hour or so and “encourages” them to make purchases.

We eventually make it to the Water Festival, which takes place in a round amphitheater. Middle-aged local women splash water from a shallow circular pool onto giggling visitors, who stand all around the edges. At one point, a fully grown Asian elephant is brought out, flapping its ears at the arcs of sparkling water landing on its back. Like our tour guide, its feelings about all this are unreadable.

The festival is not one for those in search of authenticity, unless they can find it in the faces of the women selling plastic bags of dried coconut and papaya and sugarcane juice, or the peddlers weaving through the crowd, pressing flower and nut shell garlands into hands, for a price. This is the New Year, rehearsed and paid for, but perhaps no different from any other. Soon the water women are parading around the amphitheater, baptizing us with splashes from plastic bowls.

Mechanical Buddha

A gilt Buddha statue, 49 meters high, looms over Xishuangbanna. It’s the showpiece of the Mengle Great Buddhist Monastery, the largest Theravada Buddhist site in China. 300 monks pray at the monastery daily, but today not a one is to be seen. To reach the Buddha, we take 2,000 steps up a small mountain, interspersed with temple halls.

When we reach the temple at the feet of the Buddha, an angry old man bursts out its doors. He curses the tour guide, stuffs his feet into his shoes, and flies back down the mountain. We raise our eyebrows at his apparent irreverence and step over the threshold into the cool temple.

We soon discover the reason for the old man’s rage. A guide leads us clockwise around the temple, depositing us at successive stations like children at a craft fair. At each station, we are asked in solemn tones to buy commemorative candles, statuettes, or bracelets, items which become successively more costly as we rotate along the temple—all the better to reach nirvana. A woman tries to sell us a lotus-shaped candle for 25 yuan. When we don’t take the bait, she lowers the price to 15. We escape her clutches, and the eternal spiral, by stuffing a ten-yuan bill into a donation box.

Escape leads us to an observation deck, high above the city. From here, everything is a miniature kingdom. Bridges and cars are toys, and the river is a distant ribbon. The Buddha presides over a circular plot of land, a wasted area like some Tolkienesque fortress. Officials plan to one day turn it into a park.

As we descend from the deck, we enter into another hall, occupied by a statue of a sitting Buddha. Touring monks from Thailand snap cell phone pictures. Above them, large paintings depicting Siddhartha Gautama’s life encircle the hall. They start from the entrance and end behind the Buddha’s back, like a continuous comic strip.

The paintings are strange. The usual clouds and halos mingle with weird futuristic imaginings, some downright psychedelic. In one painting, the Buddha is flanked on his left by a metallic city full of steel-blue towers. On closer inspection, floating vehicles zoom between the buildings, and in the sky are what look like flying saucers. On his right is a misty, wooded glen: Between two columns of rocks issues a mysterious blue light.

Following the progression of the paintings, I walk behind the statue. There, in the darkness cast by the Buddha’s back, is a wall to ceiling painting of a demon. His eyes bulge from his red face. His tongue lolls, and horns sprout from his veiny head. I step back quickly, but in retrospect, maybe I should have paid more attention. For if the golden Buddha could hide a demon behind his back, there may very well be an accountant inside his belly.

Market Economy

Any good trip requires an inventory of the food consumed. The complimentary breakfast buffet, an industry standard in China, is vast enough to fill any intrepid belly. Staples include steamed buns and noodle bowls, as well as sliced white bread and pastries. Buffet trays of vegetables—bok choy and potatoes fried to an oily sheen —line a banquet table. A pot of bitter Arabica coffee and a kettle of Pu’er tea, both produced in Yunnan, are nods to the local flavor. The backdrop to all this is the main Xishuangbanna hotel, boasting marble floors and a diorama with real Land Rovers.

Another staple is the convenience shop, though not the chain markets familiar in the United States. Although these small shops sell much of the same goods, they are independent, manned by their owners who sit and fan themselves behind the cash register. The shops themselves are often little more than an alcove just off the street. The narrow shelves, cluttered or neat depending on the owner’s inclination, are stocked with items like mango creme Oreos and Pocky. Each has an ice cream freezer, crammed with mung bean popsicles and ice cream cups. In warm Xishuangbanna, the freezers are insulated with a thick cotton blanket to cut refrigeration costs.

The nocturnal sibling to these shops is the Jinghong night market, which winds under the bridge over the Mekong river. Here, anything imaginable is for sale, from electronics to nail decals to long underwear to real tattoos. But we’re really here for the food, which comprises an overwhelming majority of the market. Fruit juice vendors jostle for space with barbeque stands, which will grill anything imaginable: river eel, cuttlefish, fungus, potatoes, and more. The entire scene buzzes under hot fluorescent firefly lights rigged to generators.

If the night market and the convenience shop go hand in hand, then their natural antithesis must be Xishuangbanna’s only Walmart store, at the anchor of a busy intersection. Entering the store, however, the same variety of goods and foodstuffs are found for similar rock-bottom prices. The only major difference seems to be that the store is air-conditioned and the workers are uniformed in Walmart’s trademark blue.

Land Dam

The winding old road from Kunming (the capital of Yunnan province) to Xishuangbanna to the Yunnan Tropical Botanical Garden will be replaced within the year by a new highway, which will cut travel time in half. The bones of the highway are already laid down. They embrace Xishuangbanna like prehistoric ribs.

The electric zing of steel and concrete can be heard for some time when driving on the old road, but the sound is soon lost among the banana trees, which stretch out as far as the eye can see. The trees are not tall; these bananas are a short, fat variety that must be protected against the cold night air. Each banana is individually wrapped—they look like small sleeping bags dangling from the trees.

Not to be outdone, the rubber trees, like bent beggar men, are outfitted with one wooden bowl each, tied to the trunk to catch their precious sap. Hordes of these odd couples, these stout banana trees and slender rubber trees, march over the mountains. Tourists, rubber, and bananas, in their overrunning glory, are the three mighty pillars which hold up the region’s economy.

The mighty Mekong river shoots through Yunnan province before it curves through Laos, Thailand and Cambodia and reaches the South China Sea. An inflatable boat trip down the river reveals the full scope of the highway project. A series of latticed concrete beams hold back the mountains, which have been scooped away to make way for the road. Eventually vegetation will grow between the lattices, but for now they are bald and empty. The red earth of the mountain bulges through the gaps, as if threatening to burst through. River swallows scream at the sky, and farther down the river, the forest is thick as tree moss.

Our boat docks in a tiny bay. The boatman tells us to get off and take a break as he reels in a fishing net, cast earlier that day. We climb some steps to find construction in progress. In a flat clearing, space has been made for a sandy volleyball pit. Above, workers pour gravel into metal chutes, the sound like breaking glass or miniature avalanches. Thick stacks of bamboo are everywhere. Eventually, this clearing will become a riverside resort.

We snap photos and return to the boat. The boatman has finished reeling his net. “Nothing today,” he says. “But once I caught a fish that weighed a hundred pounds.” He casts out the net again. It whirls and wheels out over the water and sinks into the current. We get back on the inflatable boat, the engine sputters to a start, and we head back toward the city.

Earthly Mysteries and Celestial Spheres

Xishuangbanna marks my third trip with a Chinese tour group. The first was a journey through Qingdao in Shandong province, best known for German influences that culminated in the form of Tsingtao beer, and its official designation as China’s Most Livable City.

The second was through Hainan, an island in the southernmost tip of China. We were plied with coconuts and fried tofu, and stuffed to the gills with seafood. Our tour guide tried to con us a couple of times, bringing us to the wrong hotel and several jewelry stores.

In each of these tropical paradise destinations, there is one constant. Red-beaked seagulls migrate every year from Siberia to winter on the temperate coasts. Since 1985, tens of thousands have alighted each winter on Kunming’s Dianchi Lake, where the local people call them “the winter angels.”

Residents and tourists, gather each year at Dianchi to greet these familiar friends. Parents, who remember the first bold flocks, now bring their children. Carts along the lake sell fluffy loaves of French bread for a few cents per bag. The visitors toss pieces of bread into the sky. With steady precision, the gulls swoop and catch. The cool lake, which rivals Lake Ontario in size, shimmers and reflects their enigmatic flight.

How they found their way across the frigid miles to Kunming is a mystery, but generation after generation they come. They must be attuned to the magnetic stars, to the music of the celestial spheres; when they are startled by some invisible sign, they lift from the lake like spirits. They come, and they leave. Where they go once winter ends, no one knows. What remains only is the hope of their return.

Features • Winter 2015 - Possession

1.

In the reign of George III, Captain James Cook, who was called captain out of necessity, he was a mere lieutenant before that, left England for that land mass in the Pacific Ocean called then Terra Australis Incognita, to observe the planet Venus as it traversed the space that stood between the Earth and the Sun. He sailed on a ship called the Endeavour and he took with him: botanists (Joseph Banks, who brought along Daniel Carlsson Solander, a disciple and former student of Linnaeus, who brought along his friend and fellow botanist Herman Sporing); artists (the painters William Hodges and Sydney Parkinson); and scientists, and it is in this way that the Second Age of European global domination begins. Cook and his crew left England in August, 1768. They stopped off in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where they noticed that there were no beggars on the streets. And if anyone told them that those former beggars now owned land and owned people to work that land, and so therefore had no need to be beggars anymore, I can so far find no record of this.

2.

A Scottish geographer named Alexander Dalrymple was originally named captain of the Endeavour on this first voyage, but the First Lord of the Admiralty, a man named Edward Hawke, objected to Dalrymple because he was not a seaman, only a mere geographer. I note Edward Hawke because I grew up in a section of Antigua called Ovals, a term associated with cricket, a sport with rules said to embody the honorable character of the English people. This place is a neighborhood made up of five streets, and each street was named after an English maritime hero/criminal: Rodney, Nelson, Hawke, Hood, and Drake. Among my daily duties was to pick up our bottle of cow’s milk from a woman who lived on Hawke Street. We lived on Nelson Street, and this was only two streets away from Hawke, but for me the journey was full of dread, for I was afraid of dogs, and there was always a dog who would bark at me, and I imagined that the bark and the bite were the same; and there was also a house in which lived a beautiful girl, not so much older than me, who did live with her mother but had silenced her, so that her mother’s commands not to play calypso music very loud, and not to congregate with boys or men were completely ignored. Her name was Marie, and she frightened me, but not for very long: She ran away to Trinidad to be with The Mighty Sparrow, and we all knew the song by him, “I love the way you walk Marie, I love the way you talk Marie,” was about her. She lived on Hawke Street, I lived on Nelson Street. The Mighty Sparrow was of Trinidad, and Trinidad is a word of Spanish origin, a word born of the imagination of that other greater and earlier explorer, whose name does not appear in James Cook’s Journals, as far as I can tell.

3.

In Rio de Janeiro, the women are addicted to gallantry. Solander notes that in the evening, women appear at every window to present “nosegays” to the men they favor.

But Solander knows flowers, and a nosegay is made up of flowers. What flowers made up these nosegays? He does not say. In any case the climate of Rio, which in August is not Summer, he finds okay. The soil, he notes, produces all the tropical fruits: oranges, lemons, limes, melons, mangoes, cocoa nuts. And then this: “The mines are rich, and lie a considerable way up the country. They were kept so private, that any person found upon the road which led to them, was hung upon the next tree, unless he could give a satisfactory account of the cause of his being in that situation. Near 40,000 (forty thousand) negroes are annually imported to dig in these mines, which are so pernicious to the human frame, and occasion so great a mortality amongst the poor wretches employed in them, that in the year 1766, 20,000 more were drafted from the town of Rio, to supply the deficiency of the former number. Who can read this without emotion!” That was on August seventh.

4.

On the eighth, they left Rio and sailed on into the Pacific Ocean where nothing happened until the twenty-second, when they came upon a colony of water-dwelling mammals, grey in colour. On the twenty-third, they witnessed an eclipse of the moon, and the next morning, this: “a small white cloud appeared in the west, from which a train of fire issued, extending itself westerly; about two minutes after, we heard two distinct loud explosions, immediately succeeding each other, like those of cannon, after which the cloud disappeared.”

(Right here I want to interject something: for the journal keeper, and this is Cook, the world is still familiar: he knows beggars and so the absence of beggars is interesting; women who are in a confined role and now women who are whores and borrowing the symbols that flag purity and worthiness; the contents of the mines being extracted by forced labour.)

5.

On the fourth of January, 1769, Cook’s crew mistook a fog bank for an island. On the fourteenth, they encountered a storm in the Strait of La Maire, but found shelter in a cove which Cook named St. Vincent’s Bay. Banks and Solander went ashore, and the journals recount: “having been on shore some hours, returned with more than a hundred different plants and flowers, hitherto unnoticed by the European botanists.”

6.

On April tenth: “looking out for the island to which they were destined, they saw land ahead. The next morning it appeared very high and mountainous, and it was known to be King George’s III’s Island, so named by Captain Wallis, but by the natives called Otaheite. The calms prevented the Endeavour from approaching it till the morning of the twelfth when, a breeze springing up, several canoes were making towards the ship. Each canoe had in it young plantains, and branches of trees, as tokens of peace and friendship; and they were handed up the sides of the ship by the people in one of the canoes, who made signals in a very expressive manner, intimating that they desired these emblems of pacification be placed in a conspicuous part of the ship; and they were accordingly stuck amongst the rigging, at which they testified their approbation. Their cargoes consisted of cocoa-nuts, bananas, breadfruit, apples, and figs, which were very acceptable to the crew, and were readily purchased.” (But how was this purchase made? There is no account of it.)

7.

Twenty days later: “Tomio came running to the tents and taking Mr. Banks by the arm, to whom they applied in all emergent cases, told him that Tubora Tumaida was dying, owing to something which had been given to him by the sailors, and prayed him to go instantly to him. Accordingly Mr. Banks went, and found the Indian very sick. He was told, that he had been vomiting, and had thrown up a leaf, which they said contained some of the poison he had taken. Upon examining the leaf, Mr. Banks found it to be nothing more than tobacco, which the Indian had begged of some of their people. He looked up to Mr. Banks while he was examining the leaf, as if he had not a moment to live. Mr. Banks, now knowing his disorder, ordered him to drink cocoa-nut milk, which soon restored him to health, and he was as cheerful as ever.”

8.

On Tuesday the ninth of May: “The natives, after repeated attempts, finding themselves incapable of pronouncing the names of the English gentlemen, had recourse to new ones formed from their own language. Captain Cook was named Toote; Hicks, Hete; Gore, Toura; Solander, Tolano; Banks, Opane; Green, Treene; and so on for the greatest part of the ships crew.”

9.

On July fourth, Banks planted “a quantity of the seeds of water melons, oranges, lemons, limes, and other plants and trees which he had brought from Rio de Janiero. He gave these seeds to the Indians in great plenty, and planted many of them in the woods: some of the melon seeds which had been planted soon after his arrival, had already produced plants, which appeared to be in a very flourishing state.”

10.

On the ninth of July, when Captain Cook wished to leave, two of his men were missing. He held important native people hostage, demanding his men be freed. But the “Indians” did not have them. They were in the mountains, they had taken wives. When his men returned, they told him that the Indians were right, they wanted to stay there, and had hidden themselves, hoping he would leave without them. In the middle of all this, Cook’s note: “They have no European fruits, garden stuff, or pulse, nor grain of any species.”

11.

Between the fifth of August and the fifteenth of August: “The island of Ohiteroa does not shoot up into high peaks, like the others which they visited, but is more level and uniform, and divided into small hillocks, some of which are covered with groves of trees; they saw no bread-fruit, and not many cocoa-nut trees, but great number of the tree called Etoa were planted all along the shore.”

12.

On the twenty-fifth of August, the adventurers from England celebrated being away from home for one year with Cheshire cheese and port, and the port would have come from Portugal or Spain, places they didn’t think much of, but which all the same contributed much to their intimate identity, their intimate mannerisms and posture, the people they were when no one cared to look. The journal records that the port was “as good as any they had ever drank in England.”

13.

Sometime around the twentieth of October: “Mr. Banks and Dr. Solander visited their houses, and were kindly received. Fish constituted their principal food at the time, and the root of a sort of fern served them for bread; which, when roasted upon a fire, and divested of its bark, was sweet and clammy; in taste not disagreeable, but unpleasant from its number of fibres. Vegetables were, doubtless, at other seasons plentiful. The women paint their faces red, which, so far from increasing, diminishes the very little beauty they have.”

14.

On the morning of November third: “they gave the name of The Court of Aldermen to a number of small islands that lay contiguous. The chief, who governed the district from Cape Turnagain to this coast, was named Teratu.”

15.

On November eleventh: “oysters were procured in great abundance from a bed which had been discovered, and they proved exceedingly good. Next day the ship was visited by two canoes, with unknown Indians; after some invitation, they came on board, and trafficked without fraud. Captain Cook sailed from this bay, after taking possession of it in the name of the King of Great Britain on the fifteenth.” (For me, it’s rare to see that: taking possession in the name of a monarch of Great Britain.)

16.

On the eighteenth (still November), Cook, Banks and Solander go off to examine a bay where a river empties. They find trees that are tall and thick in trunk, trees they have never seen before. Cook calls the river Thames, “it being not unlike our river of the same name.”

17.

William Bligh was born on the ninth of September, 1754. He joined the navy at 16. At 22, he was appointed master of the Resolution, one of the ships accompanying James Cook on his third and last voyage to the Pacific. After this, he was placed in command of ships that protected trade in the West Indies. In 1787, Joseph Banks commissioned him to go to Tahiti and collect plants of the breadfruit tree, which were to be taken to the West Indies and distributed among the many British-owned islands, where they would be grown as food for the enslaved African population. This journey was not a success. His crew mutinied, and threw him and the plants he had collected overboard. He did not sink to the bottom of the ocean, but the plants did. In an open boat that was about 20 feet long, and accompanied by some sailors loyal to him, he arrived in Timor six weeks later. In 1791, in a ship called Providence, he sailed again to Tahiti, to get some more of that same monoecious tree, and this time his efforts were successful. The men did not mutiny, but they did complain that he rationed their supply of water, all to make certain that not one plant would die. Bligh was eventually made governor of the prison colony that Australia had become, but eventually the prisoners, like his crew, mutinied against him. He was arrested and jailed in Sydney for more than a year. He returned to England in 1810 and died in 1817. He is buried in a churchyard in Lambeth, with his wife and two of his five children. In that same churchyard are buried the Tradescants, Father and Son. I once saw these graves while visiting an exhibition devoted to Gertrude Jykell. The church is now a museum devoted to the garden.

18.

The breadfruit belongs to the genus Artocarpus, and in that genus there are some 60 shrubs and trees. The genus in turn belongs in the Moraceae or mulberry family. The name Artocarpus comes from the Greek language: artos means bread, karpos means fruit. These plants were named so by Johann Reinhold Forster and J. George Adam Forster, father and son botanists who accompanied James Cook on his second voyage to the Pacific. They were passengers aboard the Resolution.

19.

HMS Providence arrived in Kingstown, St. Vincent in early 1793 with many live breadfruit plants. By then, in St. Vincent as would be so in many other islands that were British-owned, a Botanic Garden had been established. In actuality, these places were not Botanic Gardens at all. They were primarily of economic importance, involved in the prosperity of the mother country. They were modeled on Kew Gardens, which was established by Joseph Banks, who became its first Director. (The second and third were the Hookers, father and son.) Some of this first collection of breadfruit plants was also sent to Jamaica, which was the largest British-owned island.

20.

Near the end of the eighteenth century, there were many slaves in the West Indies. Certainly by then to say you were from the West Indies was to say you were black or of African descent. Europeans didn’t like living there. Most people who owned plantations paid other people to manage them. White people who lived in these places, where there were so many enslaved black people, were not considered really white people anymore: they were creole, the first meaning of that word. The word now can mean all sorts of things but it’s in that way it was first used: to designate a white person born and living in the black and enslaved world.

21.

Those many slaves had to eat food. And they had to have time to cultivate it. It isn’t hard to imagine the calculation: If an easy source of nourishment could be found for these people, they would produce more valuable goods instead of growing their own food.

22.

The slaves never liked the breadfruit. They refused to eat it. With the exception of my mother, a woman who was born on the island of Dominica, I have never met anyone who liked the breadfruit. In particular, and especially, I have never met a child who liked the breadfruit. The breadfruit is said to be bland but there are other bland foods and they are not shunned. It is said to be starchy, but I can think of many other foods that are starchy and they are not shunned.

23.

The breadfruit or Artocarpus altilis is a flowering tree in the family Moraceae. It is cultivated in a lot of places that are warm in climate all year round. It is native to the islands in the Pacific Ocean. It grows to an enormous height. Its leaves are large, thick and deeply incised. The plant yields a latex-like fluid that can be used in boat caulking. The fruits are seasonal, says a book I consulted about it, but I seem to remember it as always in season and readily available to my mother, who used to insist to me that it was of great nutritional value. The tree itself is of such generous height and breadth that it can be used as a shade tree, yet I have never seen such use made of it, even in a place as sun-drenched as the place where I grew up.

24.

My mother was born on the island of Dominica, and notice the way this is phrased: for of James Cook, I would say that he was born in a village, and that village would be in a country, not an island. An island is ephemeral, and yet James Cook was born on an island; but my mother was born on the island of Dominica, and she grew up there; she left when she was 16 years of age, taking passage in a boat that almost sunk when it ran into a hurricane in an area called the Guadeloupe Channel. She had quarreled with her family and did not see them again for 30 years. She continued her quarrel with them through letters, and those letters traveled through the postal arrangement that had been put in place by Anthony Trollope. When she was in her sixth decade of living, she began to return to Dominica and see the people who made up her understanding of the world before she knew men and children and other people. While there, she ate a breadfruit that to her had such extraordinary flavor, that she collected the seeds, and brought them back to Antigua. She planted the seeds just on the boundary of our yard, and from those seeds grew one tree of unusual height and of unusual beauty. Shortly before her son, my brother, died, there was a hurricane, one with a man’s name, and it was very destructive but we were spared, except that the breadfruit my mother had planted was destroyed. It fell down on her neighbor’s house, completely destroying it. Its loss was never spoken of with any sadness, it was just one of the many things that came from somewhere else and then disappeared into an even vaster somewhere else, which is nowhere nameable at all.

25.

If a want of food is signal of poverty, then as a child, I was never poor at all. I had an abundance of food, only all the food that was presented to me was food I didn’t like at all. I wanted food that had the names of food I had read in a book. I wanted food from far away. Once, I saw an advertisement in a magazine for beans: there were brown beans in a heap, saturated with brown sauce, and on the top of the heap was a piece of meat, glistening and large, which was pork, for underneath the image was a description of the dish, and it said it was pork and beans. I longed for it. No food my mother could cook came close to tasting the way the advertisement for pork and beans looked. I was an extremely tall and thin girl, and my mother was always making me foods that she thought I would like, and would also make me fat. Or stout. That was a compliment, a stout woman. One day she presented to me an unusual looking dish, something that looked in texture like potato, but was arranged in form like rice. I had never seen it before. In colour it looked like the breadfruit and knowing my mother, I refused it because I thought it was breadfruit. Again and again, she told me that it wasn’t breadfruit, that it was a new form of rice from England. I ate it, not with any enthusiasm, and all the time I kept saying that I was sure it was breadfruit. After I ate the meal of it, she said, yes, it was breadfruit and she told me how good it was for me.

26.

Near the end of his third voyage, which was just as spectacular as the other two, regardless of the weather, interfering with views of the transit of Venus on the first outing, and treasured friends and colleagues dying before returning from the first outing, and all the rest, while trying to return to his beloved England, which is the seventeenth largest island in the world, Captain Cook was killed by some people who seemed to wish they had never set eyes on him in the first place. I am so sorry to say my belief that they boiled and ate him after capturing him is not supported by the facts.

Features • Winter 2015 - Possession

I found out I was a man when I was nine years old.

Next to a small woodpile deep in the mountains of Kobe, my grandfather grasped my hand and put a centipede on my wrist.

“Take it,” he said. If I hadn’t smiled at its 100 orange legs, if I had recoiled instead, then maybe ten years later I would have been on that plane from Logan Airport, running towards his hospital. But when the bug coiled, my arm calmed, and I cupped the centipede, feeling my palm warm. I asked if it was poisonous.

“Men are not afraid of bugs,” he said.

So I shed my girlhood for ten long summers, and sat in my dorm room at the age of twenty, getting ready to take a bath, as my grandfather went on dying.

“Catch a flight immediately after your test, then. He’s stable right now.” My mother’s voice echoed on the tiles. Her piano-teacher voice. “Are you sure?” I said. “I’ll be there as soon as I can. Call me if anything changes.”

I set my phone down, and walked to the bathroom to fill the bath with water and set the temperature to scalding, boil-a-lobster hot. I sat naked on the white cold tile floor. My ass numbed as I waited. This was part of being a man, being able to stand the heat. This was part of being the eldest of five granddaughters, and being the only son. I dug my feet into the water, my toes leaping from it without my consent. Soon my feet lost feeling and I inched my thighs in, clenching both sides of the bath for their cold support. I watched my body swell, pinked, my skin crying. I lathered. Every summer after Kobe, my mother used to try to scrape the tan off my skin, to expose the warm whiteness of woman. She would sweep my rail body with its lack of fat or breasts, her hard fingers pinching my chin left and right as she scuffed my neck. I was burned, tarnished. Eventually she taught herself Photoshop and used that to bleach my skin.

My mother was the only one who never accepted my manhood. But even she did not make a sound when my grandmother wrapped up my long thick hair and snipped right under my ear with her gray pearl-handed sewing scissors until the rest of my hair was the same length as my bangs. She was looking at her stomach, her chin from that angle crumpling in unexpected elderly folds.

She left the room as my grandmother told me to join my grandfather. He was cutting wood.

***

My grandfather liked simple things. He wore the same sweat-stained baseball hat on his head for 22 years, but he married a woman who likes to cover her long, white fingers with amethysts. A single flaw mars her hands: an index finger crooked at the first joint to the right, bent permanently in the angle at which she pinches her embroidery needle.

Their house is filled with dozens of tapestries of embroidered cloth, not Bible verses or proverbs but explosions of vicious color, fierce shrimp and fields of flowers and dancing children and red Noh masks and castles in Scotland. She started one every time my grandfather left for a business trip, and he framed each one once he got back. Tens of thousands of stitches formed neat silk bandages over clean white cotton.

A few years after he resigned from his job as the vice president of a metalworking company, he started learning Korean with a female Korean tutor. A few months later, my grandmother caught him trying to sneak out of the house with the second-floor air conditioner.

That was when my grandmother accused him—for the first time—of having an affair.

“It’s summer,” he said. “Her children need it, and they don’t have the money to buy one. No one was using ours, anyway.”

“I don’t accept that,” my grandmother said.

I knew instinctively that he was innocent. My instinct was supported by more than the childish belief in the faithfulness of grandparents, stronger by far than the belief in the faithfulness of parents. The idea was that if they had lasted for 50 years in the prime of their lives, they had basically mastered the art of overcoming anything that could break them apart. I knew because he once said that the man of the family could not be weak, because others were.

***

In kabuki theatre, men who play women are called* onna gata*. *Gata* means mold, an example to follow. The delicate, settled gestures of kabuki men who play samurais’ wives, the lovelorn daughters of merchant families, or Yoshitsune’s mother are cast as the highest examples of form and motion for women to shadow. Successful kabuki actors are immortalized for their craft in “femininity,” and are often heralded as national treasures. Yet when women play men, they are called *otokoyaku*. *Yaku* means role, and connotes a kind of show. In the Takarazuka Revue—formed as an all-female counter movement to Kabuki 100 years ago—*otokoyaku* waltz on stage with four-inch heels, silver glitter eye shadow, and a seven-foot-tall feathered peacock tail harnessed to their backs. Their masculinity is an artificial interpretation, in which supposedly ideal male characteristics—constant declarations of love, chivalry, and honor—are acted out on stage. Audiences and fan groups are overwhelmingly women.

In the bath, I recall a page from a Takarazuka magazine that I used to subscribe to about a prominent Takarazuka actress. She had chain-smoked her voice to gravel from the age of fourteen, lowering it to the optimum male pitch, a feat made more impressive by the fact that she remained disgusted by smoke. She signed an agreement that detailed that when she married, or entered anything that could be taken as a sexual relationship—this included talking to anyone who was not a brother or a father in any personal or private setting—she would have to resign. She applied as an *otokoyaku*, cropped her hair, and watched Marlon Brando movies, absorbing male mannerisms. After 25 years of daily ballet training, singing lessons, and a grueling professional career on stage, she left the company to follow the musical troupe’s motto: “Takarazuka men become good wives and wise mothers.”

“At least I’m a woman,” I said one summer, following a dinner during which my grandfather had told one of his war stories. My mother was drying a kettle with my aunt and my grandmother. We had a little assembly line going on, and I was in charge of suds.

“Oh, are you one, now?” My mother took a white plate and raised it to the light. She then returned it to my basket, to wash again. “Tell me, exactly, how are you a woman?” My aunt laughed, and my cousins looked at me, washing carefully.

***

My grandfather used to go to the bathhouses with the workers from his father’s coal mine in Pyongyang and scrub their backs with soaped cloth just as roughly as they scrubbed his. He and his six younger sisters were born and raised outside of Japan as part of the colonization project in the Korean peninsula. My great-grandfather, along with ten other Japanese employees, oversaw hundreds of Korean workers, and sent coal for the war effort.

Near the company houses, there was a steam bathhouse, a tennis court, a swing set, and a makeshift baseball field. In winter he would skate on frozen rice paddies, and on his way home from the bathhouse, his wet towel would quickly harden into slabs of cloth ice. On sunny days, young Korean girls took turns swinging themselves high up into the air, their skirts flying in streaks of red. He took care not to watch.

My grandfather did not doubt that Japan would win the war. His father enlisted in the military, so my grandfather dreamed of joining the air force. Naturally, he skipped school with his friends most days to go to the aviation base, camouflaging planes with grass.

On August 15, 1945, my grandfather’s best friend told him that there was going to be a big announcement on the radio. My grandfather assumed that Japan was going to declare war on the Soviet Union. They gathered in the makeshift baseball field and stood to attention as the announcer told all citizens to rise.

At first, he did not understand the radio address. The radio waves were weak, the voice unsteady, using honorifics that were beyond his sixth-grade comprehension. The voice spoke soft and high, resembling that of his mother.

It was the voice of the emperor. He told them that the war was lost, that he had agreed to an unconditional surrender. That he was no longer god, but a man, just a man. They sat on the sand mound in the baseball field, and the swings were still, although the sun beat down on their necks. No one moved, but even the heavens were changing.

For a year, his family worked in the mines. Their belongings were taken and distributed among their former workers, or burned. They lived where they had housed the Koreans, where the red clay walls that invited the wind. The temperature dropped below -33 degrees Celsius. He carried pieces of heavy rail and lumber to the station and back in endless loops, tracing the steps and paths made by the friends who used to teach him Korean songs, laugh at his accent, and give him cigarettes while they all waited for his father to finish his turn in the bathhouse. These men now called him dirty, as he had teased them a year ago. One wore his father’s best coat.

By 1947, it was time to leave his homeland. It was past time. They had started to hear rumors of Japanese colonists killed by Soviet troops, by the Chinese, by the Koreans, all of whom were heading steadily south from the north. The Soviets were going to close the 38th parallel, and soon. His father started to make plans for the family to cross the parallel into American territory without him, before the border closed. His father would be forced to continue working in the Korean mines for a decade.

One day, my grandfather saw a blonde woman in a red dress standing with an officer on the station platform. She was tall, laughing, using her height to scan for someone in the crowd of troops. The officer’s chin dipped as he looked at her. My grandfather tried not to watch as he continued to walk on, hauling his rail to the mine where there was no color.

Each repatriate had a moment of realization that Japan had truly and irrevocably lost the war. For some, it was the radio address. For my great-grandmother, it was when she saw ashes instead of Tokyo. For my grandfather, it was seeing the blonde woman in the red dress, waiting on his station’s platform.

In the end, there was no safe way to cross the 38th parallel. My grandfather’s family and a few other Japanese families hired a boat to get to the south by sea, deciding to risk routine checks by Korean and Soviet troops who had prohibited any Japanese from crossing the border. When they got on the boat, his mother handed my grandfather the baby, his infant sister.

“Please take her,” she said. She then guided his sisters to the crates they would hide in for the five-day trip.

He carried his sister to his crate. He knew what this meant, what he had to do. What only he could do, because their father wasn’t with them anymore. When she cried. When Korean soldiers knocked on top of his crate, checking for warm bodies, listening for living sounds. He looked at his sister’s pink, cold nose pressed against his chest.

Her mouth was barely the size of his thumbs pressed together.

***

I got out of the bath and wrapped a towel slowly around my breasts. I fumbled in my dark room to my desk and took out a piece of notebook paper, folded in four, which I had stuck in my wallet. I hadn’t opened it since last summer, when my grandfather was in remission, when the steam was still curling in my hair and he had pushed a glass of orange juice towards me and told me to write down everything he said. On the paper were the names of a generation of men and women who left their childhood behind to raise a country out of ashes. And then there was me. I had finished my orange juice; my grandfather told me to go upstairs and sleep.

***

When I arrived, everyone was getting ready for the fu- neral, occupying the two rooms on the second floor of my

grandparents’ house: The women’s room and the men’s room. My room was full of strangers, except for my sister. She was looking in the mirror, tying up her hair. My sister, the daughter who knows before being told that she should divide her favorite type of cake into four, and that she should take the smallest piece.

“Why weren’t you here?” she said.

“What? I had a test, how could I know, dad told me I should stay in Boston.”

“You know he asked for you. He asked for you, he wouldn’t stop, he just sat there on the hospital bed connected to all these wires and asked why you weren’t there, kept on saying your name, like I wasn’t even there—”

My chin is almost on my chest, I feel so tired. Take it, take the centipede, its not poisonous; you just have to look at it carefully. Where did it go? You should’ve taken better care of it.

“I’m sorry, okay, I’m sorry, I didn’t know. I wanted to be there.”

“Try telling him that,” she said, and retied her ribbon. If only I were a girl who cried. I get up and leave the women’s room, to stand in the hallway between the two rooms. On the roof, the cicadas scream and call, and soon I am calm, but not quiet.

Features • Winter 2015 - Possession

I

Last October, I had this crazy stress dream. In it I’m face to face with Maya Deren, the author of a book I’m reading on Haiti. She’s gorgeous, which makes me nervous. “But you’re dead,” I say. It’s true: After only 44 short years her brain had hemorrhaged, in defiance of a new, improperly-prescribed medication. It was 1961, the same year my mother took her first steps.

I put a hand on her shoulder. Her bare skin is hot beneath the pads of my fingers, almost malleable, and I worry I will damage it, leaving sticky prints on her back. She might have been a sculpture in the works: still raw, still clay. I plunge my hand through her sternum, parting her ribs and holding the hot organs in my palm.

I learned about Maya Deren while trying to understand a foggy and confused memory from 2008. I was in Haiti with a friend whose family was involved with a local hospital. She and I were standing outside a small rural house. An adult pulled us aside and told us we weren’t allowed to tell anyone back home about what was about to happen. They wouldn’t like it, she said.

I don’t remember what happened next very well. In my mind it’s a montage of ringing bells, dark rooms, old picture frames and dirty glass bottles. A low creole voice assigning tasks, which our translator explains in a whisper. I imagine colored beads, playing cards, candles, alcohol. Did money change hands? The walls were very thin wood slats: The only difference between inside and outside was the shadow the tin roof cast over the room. Six months later, the infamous earthquake hit.

Sixty years earlier, Maya Deren had touched down in Port-au-Prince with no luggage and no company. At twenty-nine, she was already a legend of the American avant-garde, with two divorces under her belt, one still fresh.

She was there to gather footage for an ambitious experimental film on the ritual dances of Vodou, Haiti’s primary religion. Though politically unrecognized (and frequently repressed), Vodou’s rituals permeate nearly every corner of the country, melding with Catholic beliefs into an organic and persevering tradition. Deren was a newcomer in Haiti, and didn’t know that Vodou leaves no room for passive observation. To be present is to participate: She was yanked from the role of ethnographer, drawn into the religious life of her subjects.

Deren was possessed, at least seven or eight times, by a Vodou spirit or loa called Erzulie, the embodiment of love. Possession, in its most loose definition, is when a divinity or other external animating force takes over a body. The practice is central to Vodou, primarily occurring during energetic communal rituals, but is also common to cultures from the spirit discos of Melanesia to the shamanism of Native Americans to the Japanese folk misaki. Even Roman Catholic doctrine speaks of demons and exorcisms.

For us, possession is the exclusive domain of the horror movie industry. Something about relinquishing self-control rubs us the wrong way. Possession is sensationalized. I’m thinking of the 2002 live-action Scooby Doo movie: Everyone gets possessed at wild group rituals in an underground cave, and demons almost take over the world. Most Westerners just imagine this stuff is like a giant game of Ouija. It’s convenient to put the whole notion of possession in quotation marks, wagging bunny ears in the air like an entire culture is pretending, like the shamans of the world wink at each other when we’re not looking, in on the trick.

Deren’s direct experience put her in a unique position to translate the phenomenon of possession into familiar language. But this was a nearly impossible task: Vodou is experiential, hard to contain in pictures or words. She never finished her film, scared the footage would only further exoticize Vodou. Like Deren, I’m going to attempt to connect with ideas that have no place in our world, and inevitably I’m going to fail on some level.